Artur Schnabel (1882-1951) is best known for the first recording of the complete cycle of Beethoven piano sonatas, which he issued between 1932 and 1935. He was never a virtuoso pianist but engaged with every nuance of meaning in the musical text with remarkable intellectual penetration and eloquence. He played Schubert sonatas when they were almost completely neglected, and he viewed the task of performers as one of serving great music, “not displaying and ingratiating themselves to win over audiences.” Schnabel once said, “I have always considered applause to be a receipt, not a bill.” And the American composer Milton Babbitt famously stated, “Schnabel was the thinking man’s pianist, and in spite of that was very popular.”

Artur Schnabel: 3 Fantasy Pieces for Piano, “Diabolique” (Jenny Lin, piano)

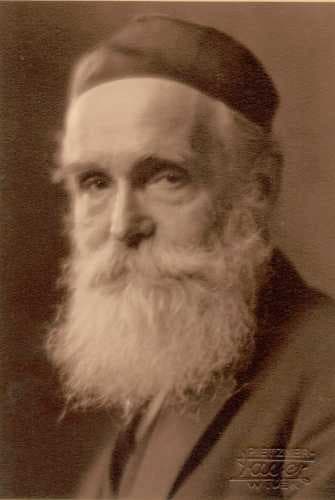

Rejected by Bruckner

Artur Schnabel

Schnabel studied with Madame Essipoff, and later with her husband Theodor Leschetizky, who observed that his young piano student had an extraordinary talent for improvisation. He also mysteriously told the young boy that he would never be a pianist because he was a musician. Until the end of his life, Schnabel maintained that he did not understand the meaning of that saying. In the event, it was decided that Schnabel should study composition with Anton Bruckner, but the “bald-headed man just grumbled ‘I don’t teach children’,” and sent him away. In the end, Schnabel studied with the famous Viennese theorist and editor Eusebius Mandyczewski, archivist and librarian at the Friends of the Society of Music and the initial editor of the complete works by Johannes Brahms.

First Compositions

Schnabel was only 11 when he composed his initial songs and some piano pieces. As Schnabel recalled, “I never worked with a teacher on form or orchestration. The only thing which I really have learned in my life was piano-playing.” Nevertheless, when Schnabel was 14, Leschetizky organized a composition contest for solo piano pieces. The compositions had to be submitted blindly, and Schnabel submitted three. Every single piece was accepted, and one of the piano miniatures, prefaced by four lines of a poem by Richard Dehmel, won first prize.

Artur Schnabel: 3 Fantasy Pieces for Piano, “Douce tristesse” (Jenny Lin, piano)

First Publications

Artur Schnabel, 1906

One of the judges was a Viennese composer who provided Schnabel with an introduction to the Simrock Publishing Company. Schnabel went to Berlin to see the publisher, and he remembers “a man with a long white beard… He said, ‘Now let me see the pieces.’ I handed him the music and after a glance at the pieces, he asked me to come back in a week. I came back to learn that they had been accepted for publication.” The original title “Three Piano Pieces,” however, was not accepted, and the pieces were renamed under the heading 3 Fantasy Pieces for Piano, 1. “Diabolique,” 2. “Douce tristesse,” and 3. “Valse mignonne.” (Jenny Lin, piano)

Artur Schnabel: 3 Fantasy Pieces for Piano, “Valse mignonne”

Eusebius Mandyczewski

In 1902, the Dreililien Publishing Company in Berlin issued Schnabel’s first volumes of songs in lavishly printed editions, but Schnabel became famous as a pianist and not as a composer. He quickly rose as a soloist, chamber musician, and song accompanist, and in 1901, made his debut as a soloist with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra with 2 movements from his own Piano Concerto in D minor. He achieved his final breakthrough as a pianist performing the piano concertos of Johannes Brahms under Arthur Nikisch in Leipzig, Hamburg, and Berlin.

Artur Schnabel: 5 Lieder (Sara Couden, contralto; Jenny Lin, piano)

Unique Directions

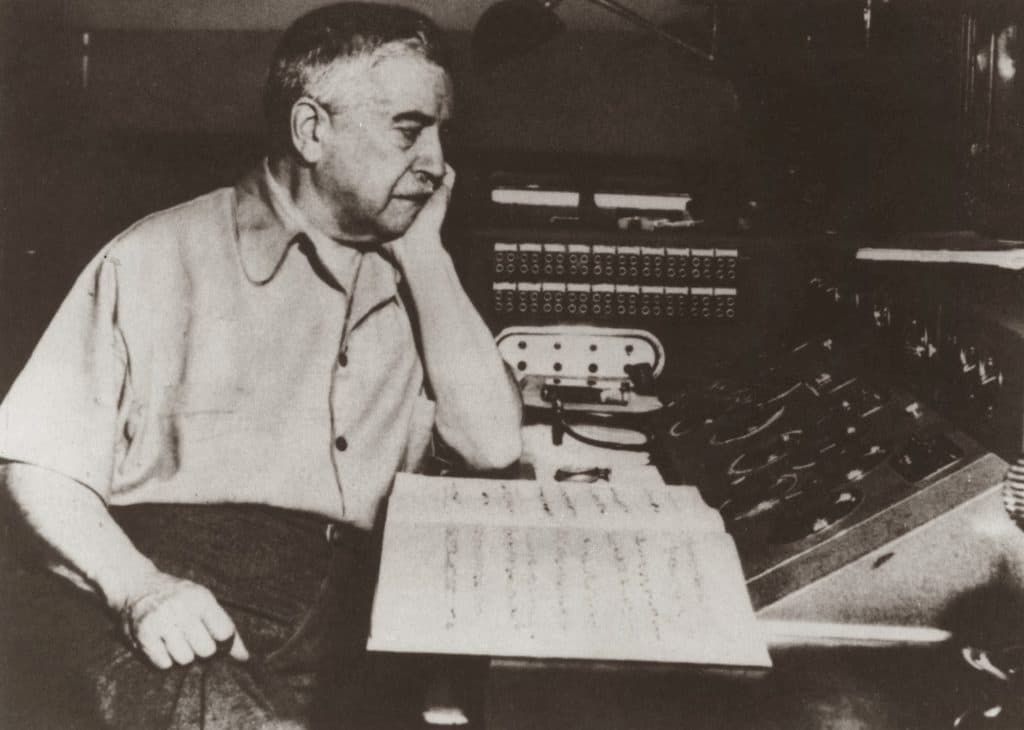

Artur Schnabel

With his pianistic fame on a meteoric rise, Schnabel reduced his compositional activities between 1905 and 1914. He founded the Schnabel Trio, and his Piano Pieces op. 15 were published in Berlin in 1907. And while his performing repertoire concentrated largely on works by Beethoven, Schubert, Mozart and Brahms, his own compositions are primarily atonal. In fact, he was a close friend of Arnold Schoenberg and supported Schoenberg’s move to Berlin in 1911. And while Schnabel occasionally conjured up a past musical language in the Notturno, the Piano Quintet composed in 1915, signaled a stylistic turn and a first step towards larger instrumental forms.

Artur Schnabel: Piano Quintet, “Rondo: Allegretto” (Irmela Roelcke, piano; Pellegrini Quartet)

Chamber Music for Strings

Interestingly, Schnabel’s emancipation from the piano as a composer was primarily defined in his chamber music for strings, and once he began to withdraw from European concert life, he devoted himself exclusively to composition. He considered the “years from 1919 to 1924 in Berlin the musically most stimulating and perhaps the happiest I ever experienced.” Until his emigration to the United States, he composed four string quartets, the Sonata for Violin Solo and the Sonata for Violoncello Solo, the String Trio, and then the Piano Sonata and the Dance Suite. “Each of these monumental compositions,” a scholar writes, “attested to Schnabel’s uncompromising and highly original musical language.”

Artur Schnabel: String Quartet No. 1, “Allegro energico e con brio” (Pellegrini Quartet)

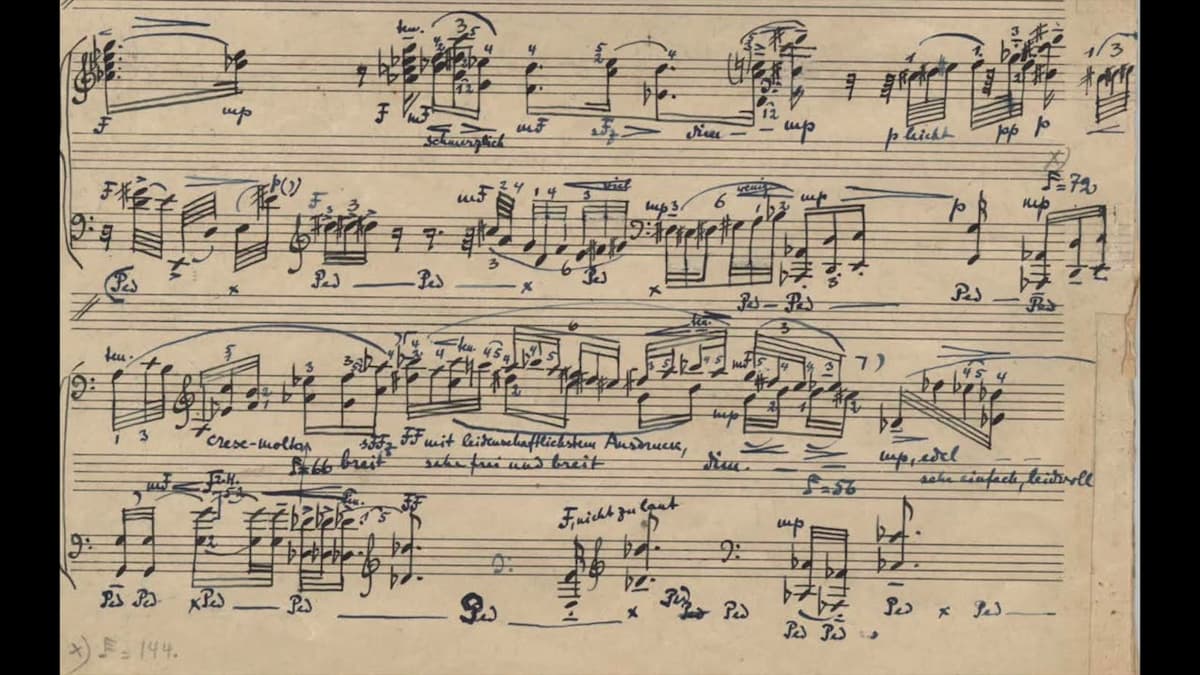

For many of the young avant-garde composers of his time, Schnabel was a “singular phenomenon of a middle-aged intellectual who delighted in the antics of the young, an artistic grand seigneur who could be as radical as the best of them.” His Sonata for Solo Violin is an atonal, freely chromatic composition in five movements and lasting nearly fifty minutes. It features no bar lines and a large number of performance directions. Schnabel writes, “I wanted to give violinists the possibility of freeing themselves from the necessity to pad out their programs with minuets and similar arrangements and to loosen their ties with the frequently intruding accompanist.”

According to a scholar, “the music is profound, uncompromising, and creates a musical universe in which the technical and timbral demands on the instrumentalist are taken to an extreme.” Schnabel subsequently described it as “salon music” as compared to the works of Schoenberg, and “if three or four violinists are able and willing to play the work, and perhaps only experts and connoisseurs are capable of enjoying it, then this would be quite sufficient for me.”

Artur Schnabel: Violin Sonata, “Zart und anmutig, durchaus ruhig” (Christian Tetzlaff, violin)

Symphonic Ambitions

Artur Schnabel’s Piano Sonata

Schnabel was actively supported by members from the Schoenberg circle, but he viewed his composing as a field of complete independence. Schnabel was never concerned about securing performances of his works, and as a pianist, he refused to do favours for composers by performing their works. Although they were good friends, Schoenberg never forgave Schnabel for never having presented any of his works, except for Pierrot Lunaire in Berlin in 1924.

Schnabel would depart from Berlin after the Nazi takeover of Germany in 1933 and, by 1939, had settled in the United States. He took US Citizenship and taught at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. As he writes, “in the years since 1939, I have devoted myself to composing, teaching, and performing. During the time from 1935 to 1939, I composed several large works—including the beginnings of the First Symphony—and since then I have written many more.”

Artur Schnabel: Symphony No. 1, “Molto Moderato”

Final Maturity

With his activities as a pianist greatly reduced in the United States, Schnabel turned his attention to several major orchestral compositions, including two further symphonies, the choral symphony “Dance and Secret, Joy and Peace,” and the Rhapsody for Orchestra. He also continued to compose in the chamber music idiom in a now reduced and even more succinct musical language. Of all the genres of chamber music, Schnabel preferred the piano trio. His Piano Trio dates from the summer of 1945, and it was written for a specific ensemble, the “Albeneri Trio.” As he wrote, “it pleases me that three highly gifted, thoroughly experienced, hardened artists show such unconditional confidence in my advice.”

A reviewer wrote, “…the great pianist, residing in New York, shows in this work as well the strictness of the thinking musician that we admire so much in his playing of Beethoven. Deeply serious, turned inward, full of warmth and reserved pathos, the three movements allow the lines a sovereign independence. For all its emancipation from the key, for all its harshness of sound, this is melodic music in the deepest sense, yes, even melodious music, frequently borne by imitation and canonic leading. One would like to hear it again and again in order to get on intimate terms with it.”

Artur Schnabel: Piano Trio, “Allegretto ma non troppo” (Ravinia Trio)

Renewed Interest

Schnabel would also return to writing pieces for the piano in an extremely sparse, almost miniaturized expressive style. His compositional aesthetic, however, had not changed. “I am very happy composing, and not even interested in the value of my compositions, just interested in the activity.” Schnabel, the composer, produced difficult yet fascinating and complex works, marked by a genuine originality of style. Some contemporaries even commented that “they show signs of undoubted genius.” Schnabel’s compositions are gradually re-emerging, with a number of works now available on dedicated recordings. We can only hope to see all of them in print and featured in recitals and concerts.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Artur Schnabel: 7 Piano Pieces (Jenny Lin, piano)

Very Wiennerisch from early to later