The last time we looked at a man with distinctive hair, we were looking at the representations of Beethoven. Now we can look at another B composer, Hector Berlioz (1803-1869). His hair was also a defining part of his imagery – both in drawings and photographs and especially in caricatures.

Let’s start with the man in reality. In this lithography by Josef Kreihuber from 1846, Berlioz’s curls come out.

Kriehuber: Ein Matinée bei Liszt (with L to R: Kreihuber, Berlioz, Carl Czerny, and Heinrich Ernst around List at the piano), 1846 (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b84265236)

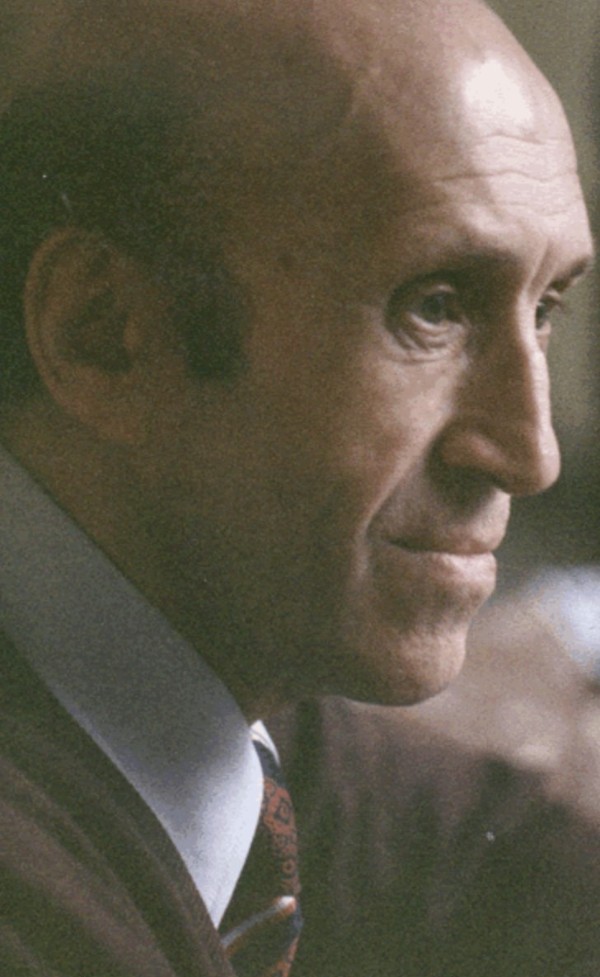

In a photograph from the 1850s, he looks much the same, although he looks like he’s wearing someone else’s coat!

Nadar: Hector Berlioz, 1890s (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b105353302)

Hector Berlioz: Beatrice and Benedict – Overture (Munich Radio Orchestra; John Fiore, cond.)

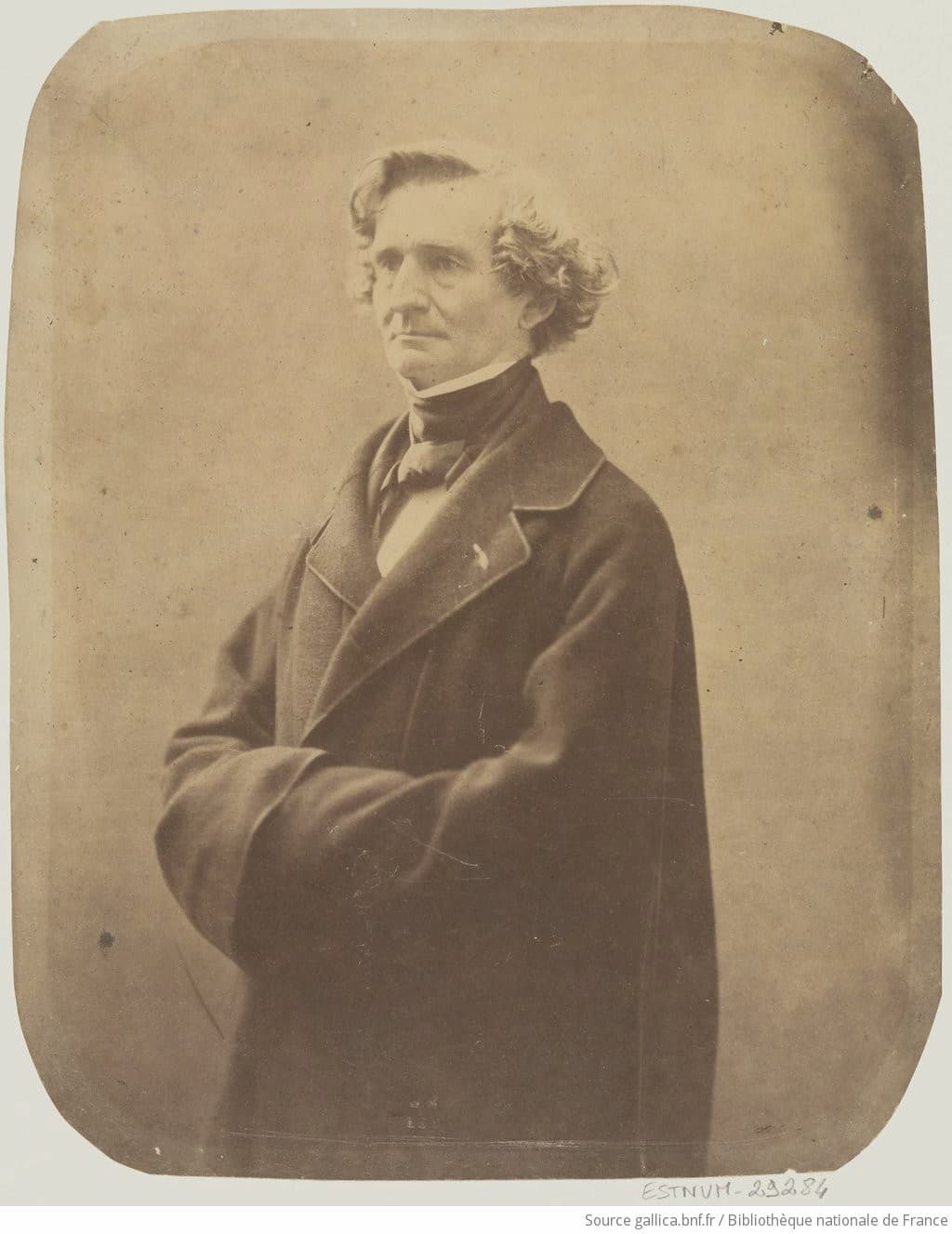

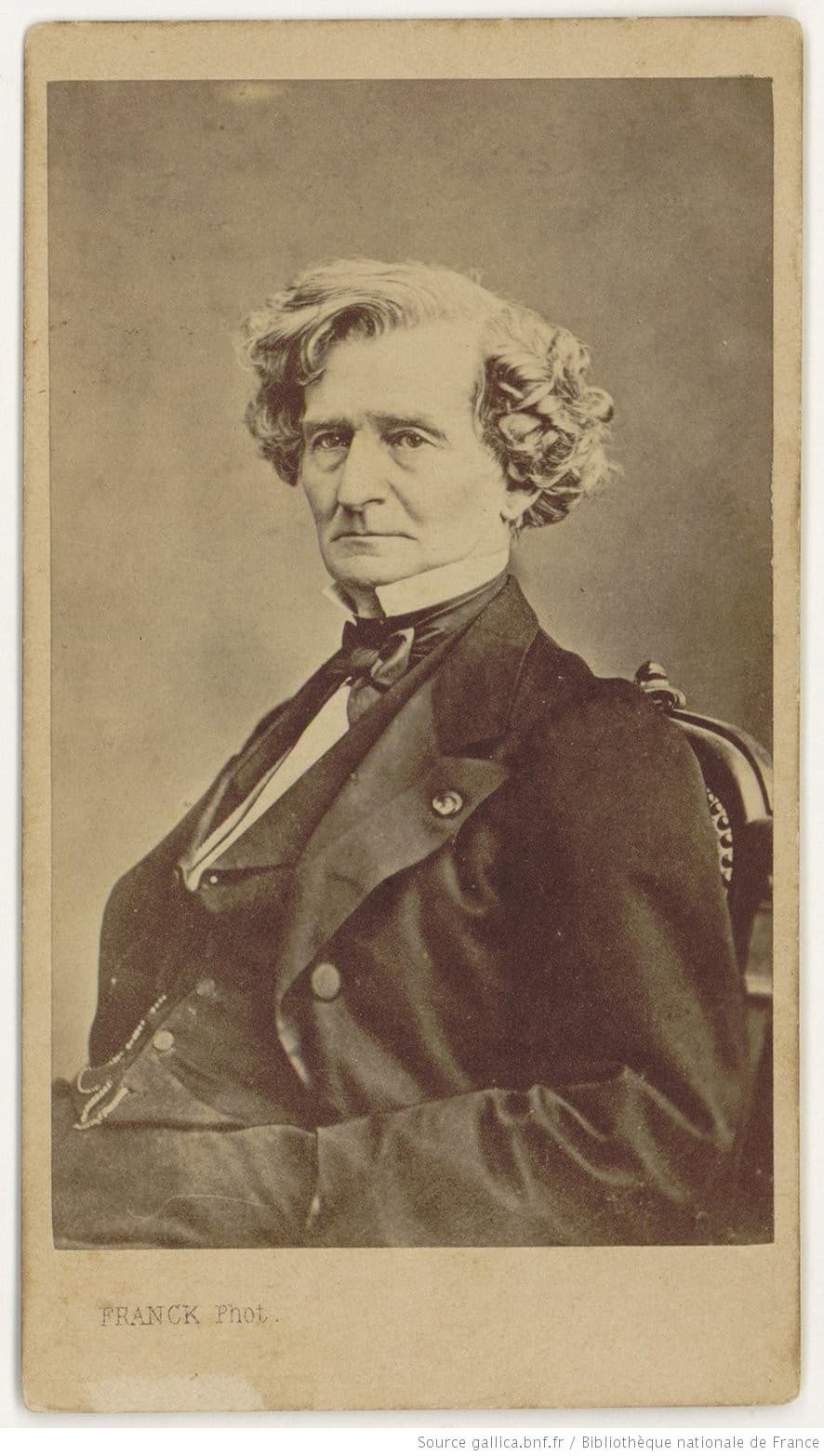

In this carte-de-visite from the 1860s, we see the 60-year-old Berlioz, hair somewhat under control – curly on the left side, combed flatter on top.

Franck: Hector Berlioz, 1860s (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b84542182)

Hector Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14 – III. Scene aux Champs: Adagio (Lyon National Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

However, to see how he was regarded by artists and critics, it’s more interesting to take a look at the caricatures that were made of him.

Berlioz’s reputation was for orchestras that were big and bigger, loud and louder, where no extreme was too much.

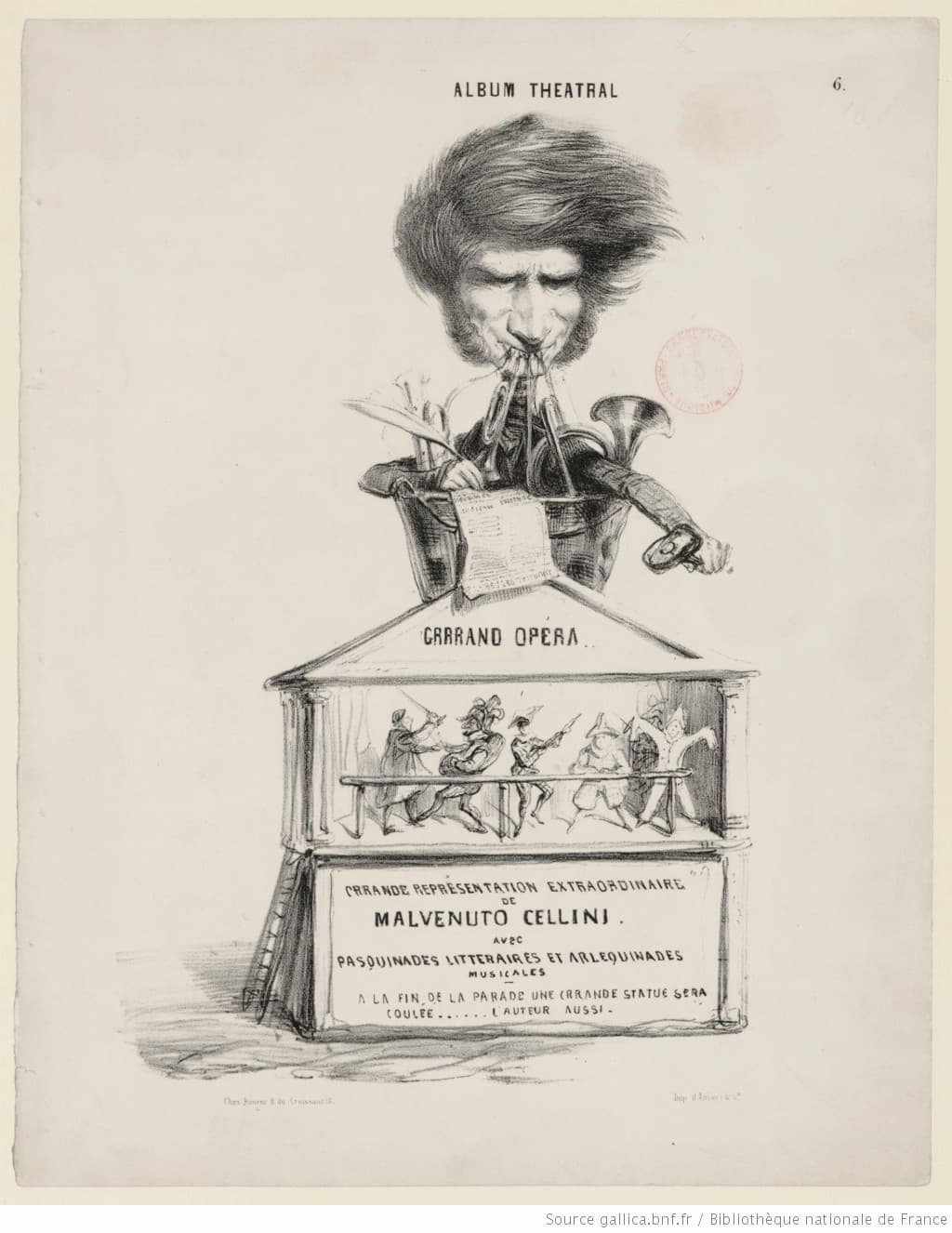

His first opera, Benvenuto Cellini, was a failure and the press of time made quick fun of Berlioz and his opera. We see in this caricature by Banger that he has re-named the opera Malvenuto Cellini. In the drawing, Berlioz, sitting atop the Paris Opéra, his hair whipped by the wind, plays all the instruments of the orchestra while hammering the pot he’s sitting in. The opera house has been renamed the Grrrand Opéra and on the stage, all the characters from the commedia dell’arte fight on stage, including Harlequin and Pierrot. In the bottom, there’s an advertisement for ‘Grrande Representation extraordinaire de Malvenuto Cellini avec Pasquinades Litteraires et Arlequinades Musicales’ and advising ‘A la fin de la parade une Grrande Statue sera coulée…l’auteur aussi’ (At the end of the parade, a large statue will be cast… so will the author).

Banger: Hector Berlioz, 1837 (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b8415753f)

Hector Berlioz: Benvenuto Cellini, Op. 23 – Overture (Lyon National Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

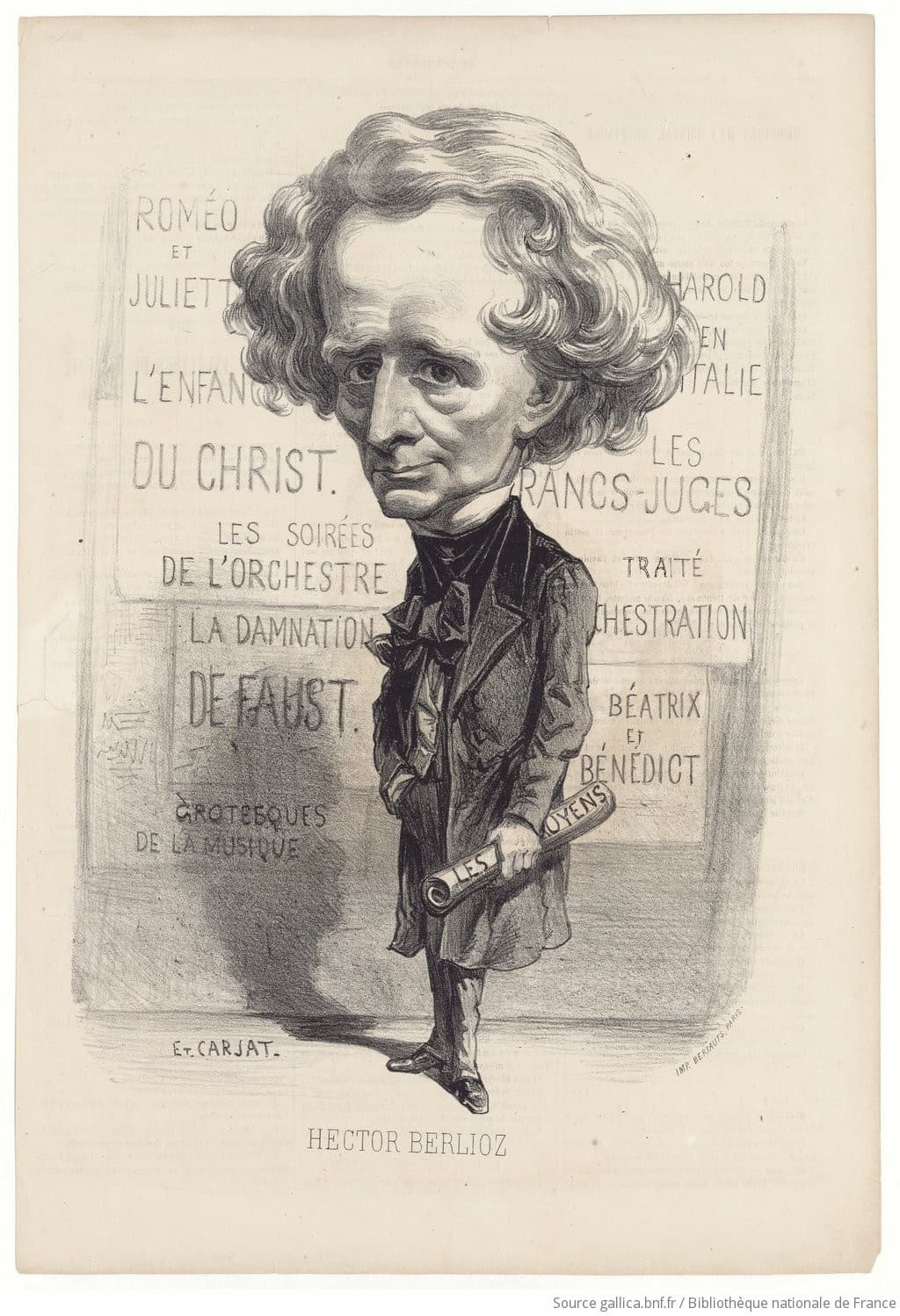

In this 1862 lithograph by Étienne Carjat, the large-headed Berlioz stands in front of a list of his operas and his books, with a title below saying ‘Grotesques de la musique’. In his hand, to be unfurled is his last opera, Les Troyens.

Carjat: Hector Berlioz, 1862 (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b8454326z)

The caricaturist Grandville captured Berlioz with his hair waving like a flag, poised to conduct Un Concert a mitraille et Berlioz (A Concert with Grapeshot and Berlioz) with a small cannon carefully stashed in the double-bass section and the tubas looking much like mortars. This illustration comes from Louis Reybaud’s 1846 humorous novel Jérôme Paturot à la recherche d’une position sociale (Jérôme Paturot Looks for a Social Position). In 1840s Paris, the name ‘Jérôme Paturot’ stood for ‘the man who imagines himself fitted for everything and cannot make a success of anything’. Grandville’s drawing was inspired by the premiere of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique in 1830.

![Grandville : "Un concert à mitraille et Berlioz" [A concert of cannons and Berlioz] (1845) (L’Illustration)](https://interlude-cdn-blob-prod.azureedge.net/interlude-blob-storage-prod/2021/04/berlioz-grandville-1846.jpg)

Grandville: Un Concert a mitraille et Berlioz, 1846 (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b84542256)

Hector Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14 – V. Songe d’une nuit de Sabbat (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Roger Norrington, cond.)

Honoré Daumier, in Les saltimbanques, published in the journal Le Charivari in 1843, shows Berlioz being exhibited as one of the grand celebrities of France’s literary, musical, and artistic worlds. Berlioz, wrapped in a musical score, is shown along with Pierre-Jean David D’Angers (sculptor), Paul Delaroche (painter), Jules Janin (writer and critic), and Victor Hugo (writer). You know Berlioz from the score…but also from his hair.

Daumier: Les Saltimbanques, 1843 (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b8454226m

In this bust sculpted by Dantan Jeune in 1833, it’s pure caricature. It’s all about the wild hair and the amazing sideburns. Note the name on the base, given as a rebus: BER and then a high bed or, in French, lit haut: BER-lit-haut (same pronunciation as Berlioz).

Dantan Jeune: Hector Berlioz, 1833 (Paris. Musée Carnavalet)

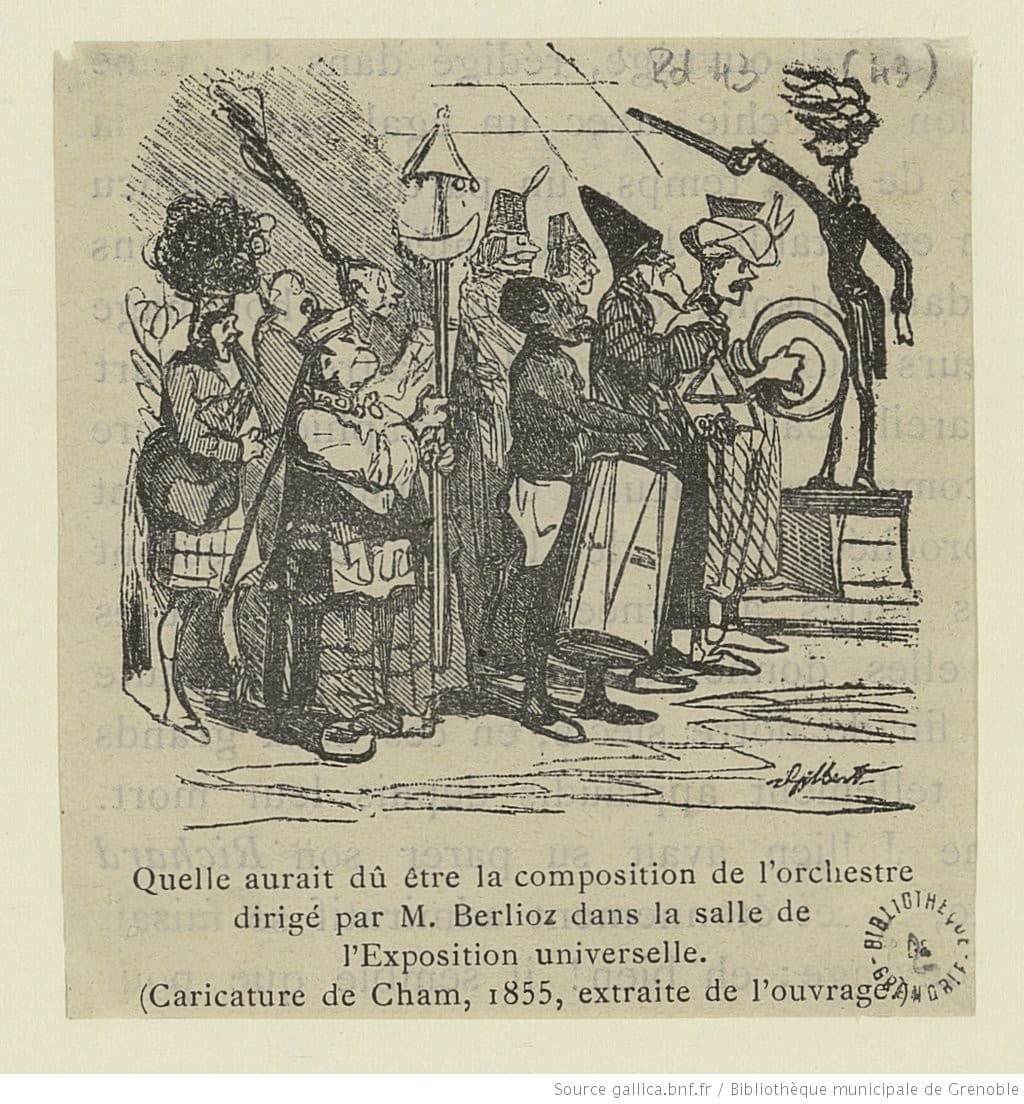

In 1855, at the International Exposition, it’s Berlioz conducting an orchestra of musicians from all over the world: kilted Scottish bagpipers, Chinese percussionists, African drummers, and so on. Berlioz could be anyone, except for his hair.

Cham: Hector Berlioz in Quelle aurait dû être la composition…, 1855 (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b106637968)

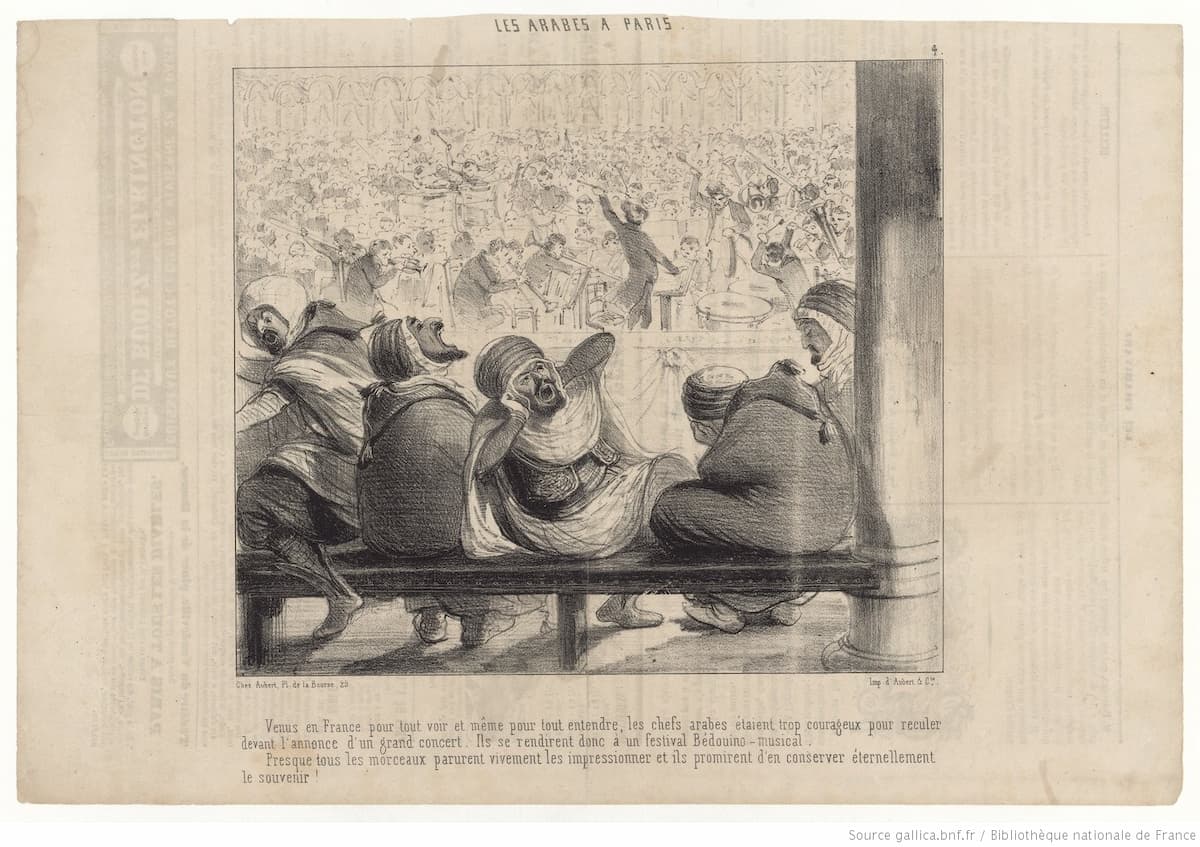

Here, Berlioz’s music is regarded as unlistenable by Arabian visitors to Paris, depicted screaming and covering their ears.

Benjamin: ‘Les Arabes à Paris’, Le Charivari, 1845 (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b8454228f)

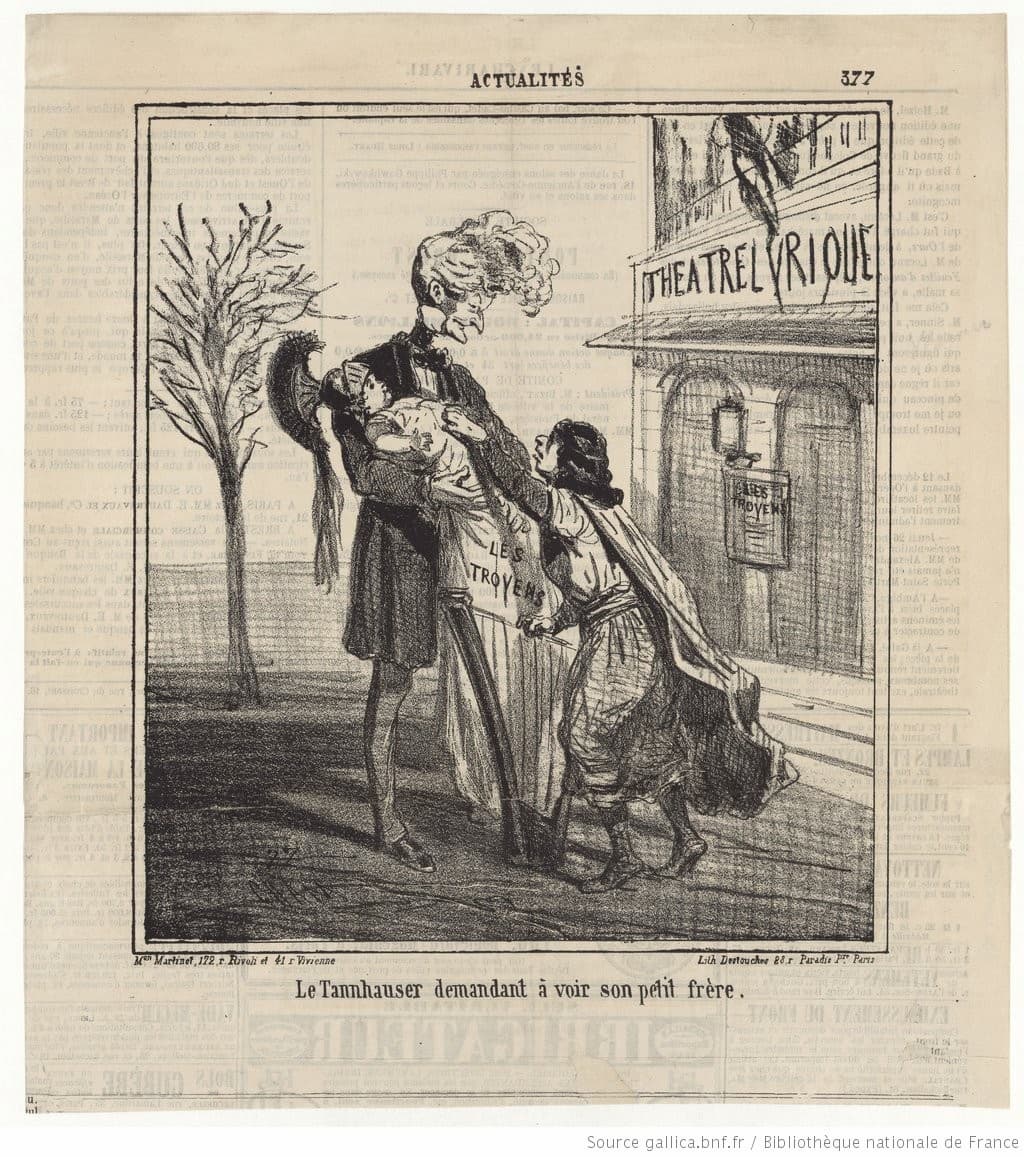

In 1863, Cham again took up Berlioz. In front of the Théâtre Lyrique, where Berlioz, tired of waiting for the Paris Opéra to make a decision on staging the work (they vacillated from 1858 to 1863), went to the smaller Théâtre Lyrique for a staging of only the second part of Les Troyens. As Berlioz later despaired, it was not a good idea. He said about Léon Carvalho, the director of the theatre: ‘His theatre was not large enough, his singers were not good enough, his chorus and orchestra were small and weak’. Ballets and set scenes were cut left and right, in one case because the scene change was taking nearly an hour and in another because Carvalho found the scene boring. In this cartoon, Cham shows Wagner’s Tannhäuser asking to see his little brother, both being complex and over-long operas. Berlioz, holding the baby Trojan, is all hair, with an extended nose and chin.

Cham: ‘Le Tannhauser demandant à voir son petit frère’, Le Charivari, Nov. 1863 (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b84542271)

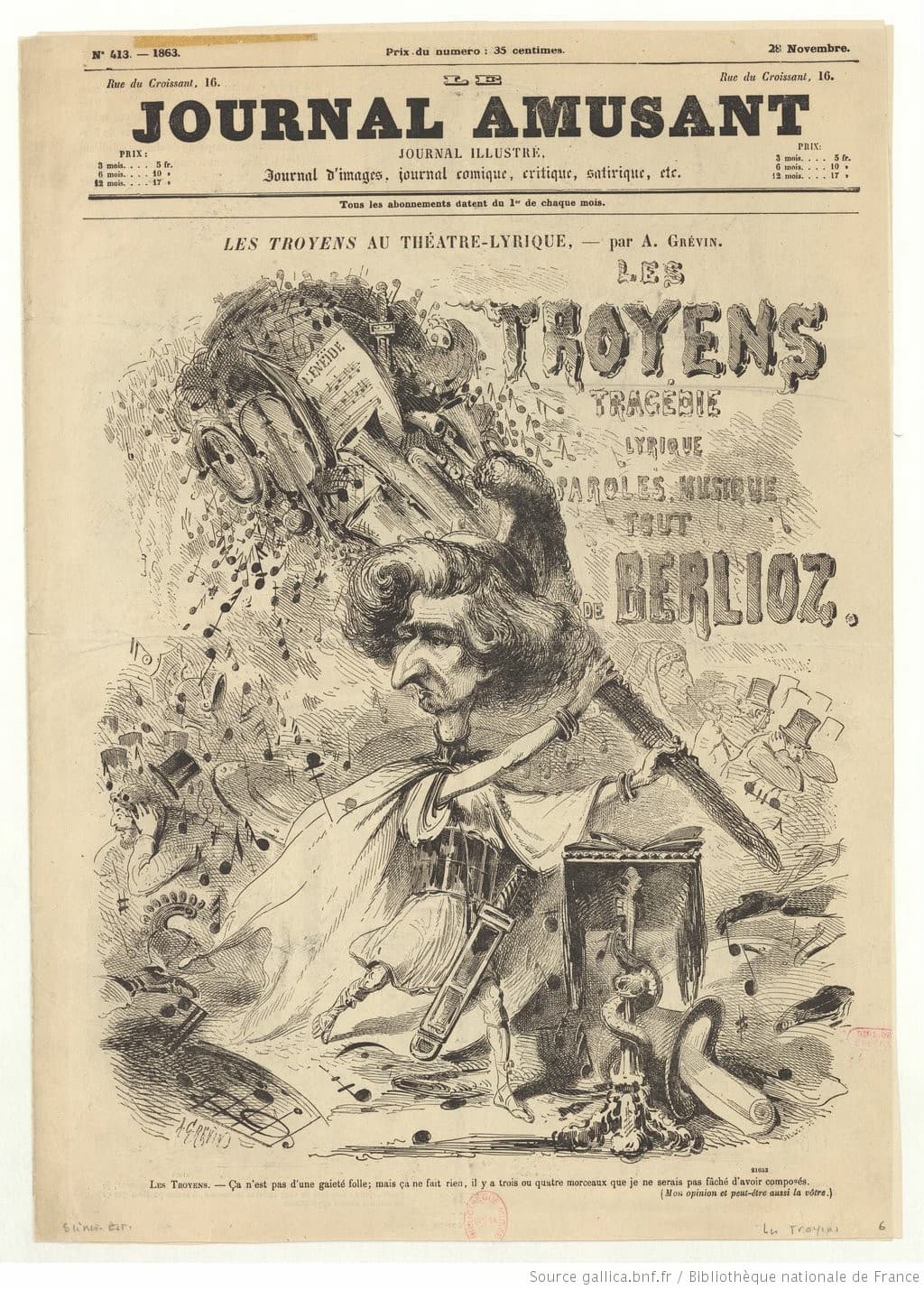

Even more critical is Alfred Grévin’s cover of Le Journal amusant on Berlioz. Berlioz is shown in Trojan garb laying waste with his music to the audience and maybe even the orchestra. Three internal images in the 5-page paper also catch Berlioz.

Grévin: ‘Les Troyens au Théâtre Lyrique’, Journal amusant, 28 Nov 1863, cover (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b53118264k)

Hector Berlioz: Les Troyens – Act I: Malheureux roi! (Deborah Voigt, Cassandra; Montréal Symphony Orchestra; Charles Dutoit, cond.)

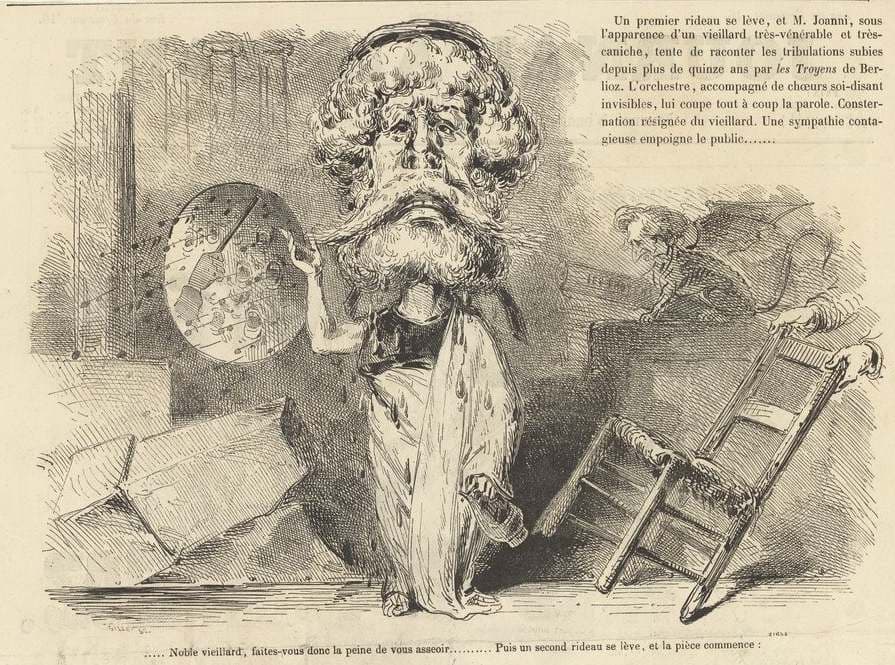

The opera opened with a telling of the first 15 years of the story, told by the character Le Rapsode, played by the actor Jouanny (here spelled Joanni), formerly a bass singer at the Opéra-National.

Grévin: ‘Les Troyens au Théâtre Lyrique’, Journal amusant, 28 Nov 1863, p. 2, detail (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b53118264k)

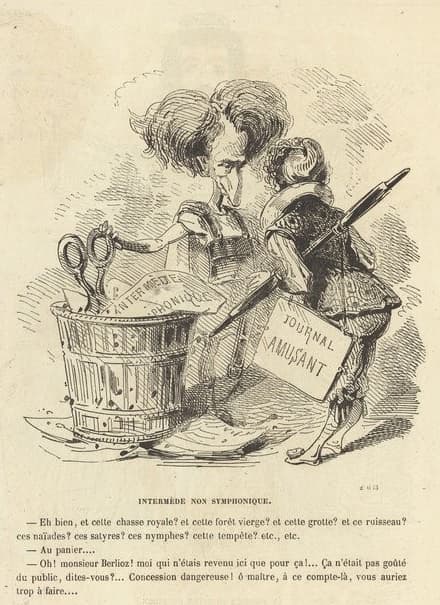

Here, the Journal amusant is sympathising with Berlioz on the removal of so many scenes: the royal hunt, the virgin forest, the grotto, and so on. Berlioz is downcast and even his hair seems depressed.

Grévin: ‘Les Troyens au Théâtre Lyrique’, Journal amusant, 28 Nov 1863, p. 4, detail (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b53118264k)

Hector Berlioz: Les Troyens – Act IV: Chasse royale et orage (Pantomime) (Royal Opera House Chorus, Covent Garden; Royal Opera House Orchestra, Covent Garden; Colin Davis, cond.)

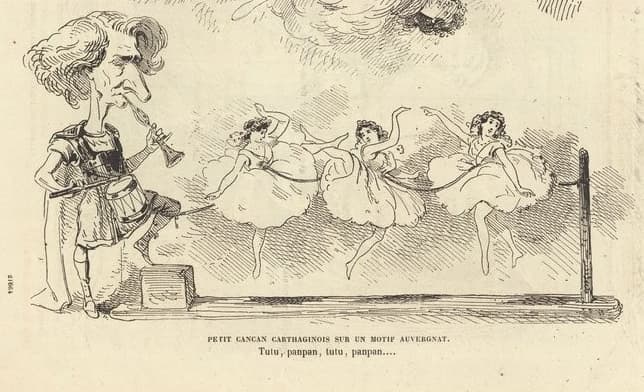

Berlioz, still in Trojan garb, playing the pipe and tabor for a can-can by the Carthaginian women on a motif from the Auvergne: ‘Petit cancan Carthaginois sur un motif Auvergnat. Tutu, panpan, tutu, panpan’. The dancers are tied to his knee and float in the air and his hair seems to have recovered some of its normal exuberance.

Grévin: ‘Les Troyens au Théâtre Lyrique’, Journal amusant, 28 Nov 1863, p. 4, detail rotated upright (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b53118264k)

A complete staged performance of Les Trojans did not take place until 1890, 21 years after Berlioz’s death, but in Germany, not in France, and with revisions. The first full production in Paris wasn’t until 1921, although there had been an earlier production in Rouen.

The first complete score wasn’t published until 1968 (earlier scores had been abbreviated by Berlioz under protest), and a complete performance was released in 1970, based on the Covent Garden production. It wasn’t until these complete editions and performances took place that Les Troyens could be truly judged. Earlier opinions considered it as a kind of ‘noble white elephant – something with beautiful things in it, but too long and supposedly full of dead wood’. After 1970, however, the opera underwent a revision in opinion: it is now considered by some critics to be one of the finest operas ever written.

The caricatures show us the man as his contemporaries saw him: indomitable, excessive, and quintessentially French. They saw him as a model and a warning against hubris (Mal-venuto Cellini, indeed!), but also, particularly in the case of the battle to get Les Troyens staged, as someone larger than life.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter