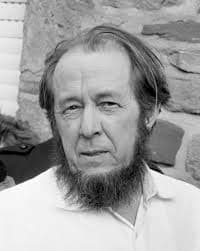

Published in 1962 with the approval of Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn tells the story of a typical day in the life of a typical labor camp prisoner. The main character is a carpenter of rural origins who is serving a ten-year prison sentence for alleged treason. Solzhenitsyn’s text was the first to “describe explicitly the circumstances in the labor camps: the prisoners’ eternal hunger, forced labor under terrible conditions, the arbitrariness of the camp administration.”

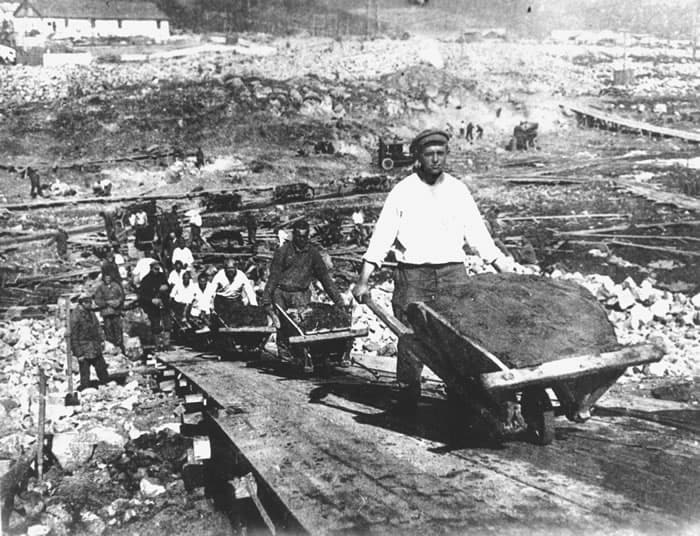

Prisoners work at Belbaltlag, a Gulag camp for building the White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal © gulaghistory.org

The novel was a sensation, as it reported on the injustices that millions of Soviet citizens had experienced in the Gulag prison camps. The Gulag was a system of 53 camp directorates and 423 labor colonies scattered throughout the Soviet Union. Prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, it is estimated that somewhere between 2.3 and 17.6 million prisoners lost their lives. The biggest percentage of inmates fell under the “political prisoner” label, and that included opposing members of the Communist Party, military officers, and a huge number of educated people and ordinary citizens, including doctors, writers, intellectuals, students, scientists and artists.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

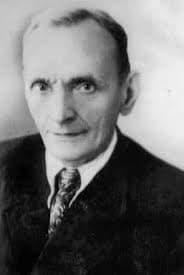

The composer Matvei Pavlov (1888-1963), aka Azancheev, was imprisoned for 10 years for reportedly telling a joke. A professional cellist and conductor, he became a prodigious composer of music for the guitar, as that was the only instrument he had access to in the prison camp.

Matvei Pavlov-Azancheev: Sonata of Moods, “History of the Russian Guitar” (Oleg Timofeyev, 7-string guitar)

Matvei Pavlov-Azancheev

Artists and composers were a favorite target of the Soviet terror state. Lenin unambiguously stated, “Every artist, everyone who considers himself an artist, has the right to create freely according to his ideal, independently of everything. However, we are Communists and we must not stand with folded hands and let chaos develop as it pleases. We must systemically guide this process and form its result.” In other words, if the government didn’t like the outcome of your freely created art, you most likely fell victim to the apparatus of terror.

Alexander Vasilyevich Mosolov

Alexander Vasilyevich Mosolov (1900-1973) was one of the driving forces in experimental Soviet music during the 1920s. He explored the expressive potential of motoric rhythms, melodic angularity, percussive attacks, and pungent dissonance. As you might imagine, such musical experimentations quickly fell foul of authorities, and it didn’t really help that he had a decidedly cosmopolitan outlook. He spoke French and German and had visited Paris, Berlin, and London. He met Prokofiev, who praised him “as the most interesting of Russia’s new talents.” However, his musical style was soon attacked for its pessimism and modernist leaning, and he was told to develop an interest in folk music instead. To no avail, Mosolov was arrested in 1937 for “counter-revolutionary activities” and sentenced to eight years in the Gulag. “Through the offices of some well-connected colleagues, he was released after only eight months, but his spirit broken, his brilliant future as a composer was never fulfilled.”

Alexander Mosolov: Piano Concerto, Op. 14 (Steffen Schleiermacher, piano; Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra; Johannes Kalitzke, cond.)

Mieczysław Weinberg

The infamous Zhadanov Doctrine announcing Stalin’s anti-Semitic purges states, “The only conflict that is possible in Soviet culture is the conflict between good and best.” In charge of ideology, culture, and science, Zhadanov began a campaign of extinguishing works exhibiting traits of cosmopolitanism and formalism, “and in particular anything produced by Jewish artists and thinkers.” On the very day that Zhadanov made his announcements on behalf “of compositions that glorify the achievements of the Soviet Union,” Mieczysław Weinberg’s (1919-1996) father-in-law was murdered by the Soviet secret police. Weinberg himself was placed under surveillance, and arrested in 1953 for “making propaganda for the establishment of a Jewish state in the Crimea.” He spent three months in pretrial detention and was only saved from execution by a letter Shostakovich personally wrote to Stalin protesting Weinberg’s innocence. Weinberg was never sent to the gulag, but for the rest of his life, he was terrified of the infamous nighttime knock on his door.

Mieczysław Weinberg: Chamber Symphony No. 3, Op. 151 (East-West Chamber Orchestra; Rostislav Krimer, cond.)

Alexander Moiseyevich Weprik

Alexander Moiseyevich Weprik (1899-1958), considered the “greatest composer of the Jewish School in the Soviet Union,” grew up in Warsaw and studied music in Leipzig. The family moved to Russia, and Weprik helped to establish the Society for Jewish Music. He became a professor and eventually dean at the Moscow Conservatory, and during a business trip in 1927, he met Arnold Schoenberg, Paul Hindemith, Maurice Ravel, and Arthur Honegger. His music was well known and performed in Berlin and by Toscanini in New York. However, in 1950 he was arrested as a “Jewish nationalist” and tortured in prison. Deported to the Gulag he initially had to endure hard labor, but was later tasked to organize an amateur orchestra among the prisoners. Music was performed in the gulag in a variety of contexts, but music-making was built around the stated goal of re-educating prisoners. In truth, it was hoped that music would increase labor productivity and improve discipline. Weprik’s case was reviewed in 1954 and after his acquittal, he returned sick and weary to Moscow. His life has been described as symbolic of the short history of Jewish music in Russia. “The career of a composer, that had started on stages in Moscow, New York, Berlin, and Vienna, ended in the Gulag with arrangements for a balalaika orchestra.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Alexander Weprik: Piano Sonata No. 1, Op. 3 (Jascha Nemtsov, piano)