Basque composer Jesús Arámbarri (1902-1960) used both his Spanish and Basque links in his music. On one hand, the Spanish tradition of composers such as Felipe Pedrell, and Isaac Albéniz were valuable, but the addition of the music of his fellow Basque composer (José María Usandizaga, Jesús Guridi and Father José Antonio de Donostia) gave an added dimension to his work.

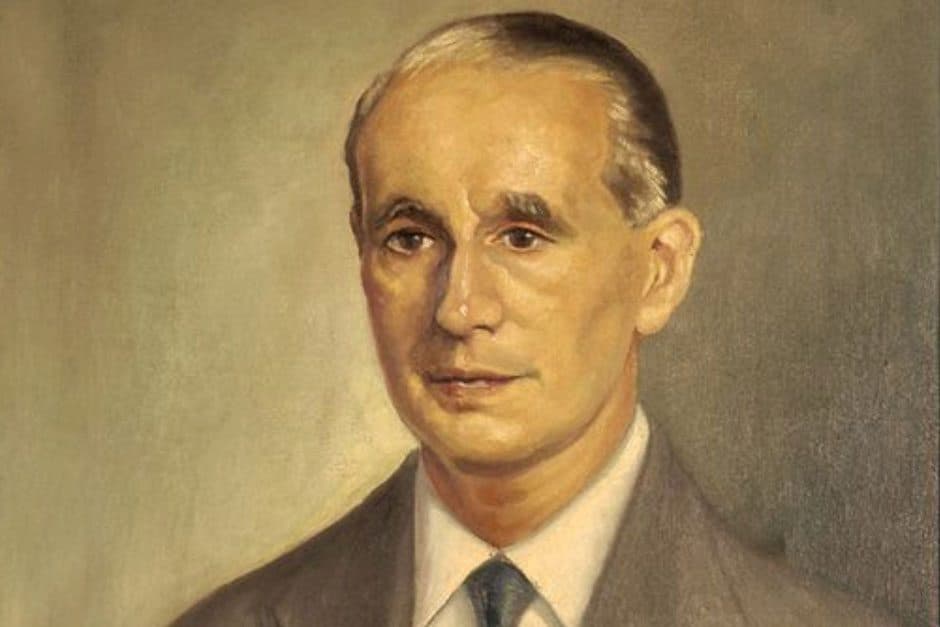

Dora Roda: Jesús Arámbarri

Arámbarri was born in Bilbao and did his initial musical studies at the Bilbao Conservatory of Music; he extended those studies with further work on composing in Paris with Paul Le Flem, Paul Dukas, and Vladimir Golschmann, and conducting with Felix Weingartner in Basel. A composer in his early days, he shifted over to conducting when he returned to Bilbao in 1932, initially taking over the leadership of the Municipal Band, then founding the Municipal Orchestra, while also leading the Bilbao Symphony Orchestra. He also conducted all the major Spanish orchestras and was influential in the introduction of new works. Most of the pieces he wrote after he became a conductor were memorial works for the deaths of friends, including In memoriam for Juan Carlos de Gortázar (1939), which includes a quote from the Dies irae; Ofrenda (Offering) for Manuel de Falla (1946), which was written in one night and performed on the next; and Dedicatoria (Dedication) for Javier Arisqueta (1949).

Raphael Infantes: Jesús Arámbarri, 1960

Arámbarri’s style involved taking pre-existing material, such as a folk song, and creating works noted for their melodic and transparent writing. His 1931 work Gabon-zar sorgiñak (Witches on New Year’s Eve) shows his skill at isolating orchestral timbres, while using a small ensemble and passing motifs from one instrument or instrument group to another seamlessly.

The work is in three parts, opening with a brisk brass declaration that’s almost a fanfare. The strings enter with the same material. It’s not quite dance-like, but there’s certainly movement in the music.

Jesús Arámbarri: Preludio Gabon-zar sorginak (Witches on New Year’s Eve): I. (Bilbao Symphony Orchestra; Juanjo Mena, cond.)

The second section, as we expect, offers a change in feeling; it’s slower and more melodic, in contrast to the sharp declarations of the first section. It ends with a solo horn call.

Jesús Arámbarri: Preludio Gabon-zar sorginak (Witches on New Year’s Eve): II. (Bilbao Symphony Orchestra; Juanjo Mena, cond.)

The final section returns us to the quick tempo of the opening, but now the feeling is more fraught and dangerous until a sprightly melody clears all the noise away. The theme from the first section returns but combines with the feeling from the second section to come to a calm ending.

Jesús Arámbarri: Preludio Gabon-zar sorginak (Witches on New Year’s Eve): III. (Bilbao Symphony Orchestra; Juanjo Mena, cond.)

There’s an association between witches and the Basque country, with the largest witch trial in Europe in the 17th century being held in the Basque country by the Spanish Inquisition. Between 1609 and 1614, some 7,000 people were accused of witchcraft in the area and underwent trial. In the end, 11 people died, 6 at the stake and 5 in prison. The 7,000 were not all women; 40% of the accused were male.

Goya: Witches’ Sabbath, 1798 (Madrid, e Museo Lázaro Galdiano)

Given the sprightly nature of Arámbarri’s work, he’s not basing his piece on these trials but on folksongs about them. We don’t know what song he used, but the folk songs of the region with witch references seem to have repeating imagery. Sometimes the songs are about groups of women where the men viewing them cannot understand their actions or, worse, the women are drinking and gambling; sometimes it’s about a he-goat in the garden. Sometimes they call out the clergy for disguising their lust for women as witch-seeking. The actions of the early 17th century is reflected in the folksongs, and these were picked up by Arámbarri as part of the Basque traditions he valued.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter