George Gershwin

George Gershwin thought of himself as “a modern romantic” but more than any other American composer of the period “his impact on the American musical scene is of social as well as musical significance.” The son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, born on 26 September 1916, was businesslike, and he fulfilled contracts and got paid vast sums of money. He did not suffer from false modesty, and he certainly did not fit “the popular notion of the serious composer with long-flowing unkempt hair, indifferent to appearance and to mundane matters.” He grew up in the streets of New York, and was “restless, lively, mischievous and a self-sufficient youngster who exhibited no intimations of artistic talents.” Gershwin’s parents, Moshe (Morris) Gershovitz and Rose Bruskin, emigrated from the area of St. Petersburg, Russia, to the United States in the 1890s and settled in New York, where they met and married in 1895. Living mostly on New York’s Lower East Side, the union would produce six children, and since the “head of the house of Gershwin liked to live within walking distance of his place of business, that family occupied twenty-eight different dwellings.”

George Gershwin: Tell me More: Kickin’ the Clouds Away (version for piano) (George Gershwin, piano)

George Gershwin with his mother and his brother Ira

George remembered, “There is nothing I can really tell of my childhood… except that music never interested me, and that I spent most of my time with the boys in the street, skating and, in general, making a nuisance of myself.” He was described as a hyperactive boy, light, wiry, competitive and good in street games and, on occasion, fights.” And he had absolutely no interest in school. When his school arranged a noontime violin recital by the eight-year-old Max Rosenzweig, Gershwin was predictably absent. Like his schoolmates, Gershwin “dismissed music study as only fitting for girls or effeminate boys.” Yet, listening to the music from the schoolyard, something caught his attention and he was determined to talk to Max. “I found out where he lived,” reports Gershwin, “and dripping wet as I was, trekked to his house, unceremoniously presenting myself as an admirer. Maxie had left by this time, but his family was so amused that they arranged a meeting. From the first moment, we became the closest of friends.”

George Gershwin: “Rialto Ripples” (Fazıl Say, piano)

George and Rose Gershwin

When the Gershwin family bought a piano around 1910, it had been intended for Ira, “but George immediately took it over.” Ira later reports, “no sooner had the upright been lifted through the window of the front room that George sat down and played a popular tune of the day. I remember being particularly impressed by his left hand. I had no idea he could play and found that despite his roller-skating activities, the kid parties he attended, the many street games he participated in—with an occasional resultant bloody nose—he had found time to experiment on a player piano at the home of a friend.” George progressed quickly in lessons with neighborhood teachers and in his early teens was accepted as a pupil of Charles Hambitzer, a piano teacher who was also a performer and composer. Gershwin called him “the first great musical influence in my life,” as Hambitzer took his young charge to concerts and assigned him pieces by Chopin, Liszt and Debussy. He later told a colleague, “I have listened to him playing classics with great rhythmic extemporizing, and I have not discouraged him.” Unsurprisingly, “Ragging the Traumerei” was one of the young man’s first compositions.

George Gershwin: Capitol Revue: Swanee (version for piano) (George Gershwin, piano)

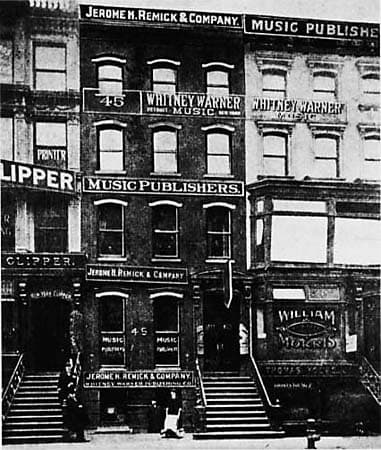

Tin Pan Alley

By now, it was clear to everyone that George had a natural talent and innate gift for making music. His parents, however, weren’t convinced at all and demanded that George become an accountant. No such luck, as George was told of an opening in Tin Pan Alley, an area between Fifth and Sixth Avenues of Manhattan. It was home to a vast collection of music publishers and songwriters in New York City that dominated popular music in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The job description advertised for a “pianist in the professional department” of Jerome H. Remick & Co., on West Twenty-eight Street. After some hesitation, the manager Mose Gumble offered Gershwin fifteen dollars a week to join his staff as a “piano pounder,” demonstrating Remick’s songs, accompanying “pluggers,” essentially vocal demonstrations, and pushing Remick’s songs on vaudeville performers, musicians, and dancers. As a biographer wrote, “in 1914 the weekly wage was considerable, and George wanted the money more than a high school diploma, or life as an accountant.” His father was relieved, as he had predicted that George would end up a vagabond, playing the piano was clearly better. However, his mother protested as “she was against my becoming a musician, as she didn’t want me to be a twenty-five-dollar-a-week piano player all my life, but she offered very little resistance when I decided to leave high school to take the job.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

George Gershwin: Song-Book (Enrico Fagnoni, piano)