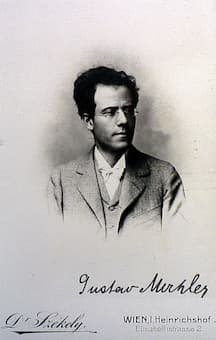

Gustav Mahler

On 9 June 1902, Gustav Mahler treated the audience in Krefeld to the premiere of his complete 3rd Symphony. The second movement alone had first sounded on 9 November 1896, and the second, third and sixth movements on 9 March 1897. This choral symphony, the longest symphony in the standard repertoire, was greeted with triumphant success. Particularly the last movement was singled out for praise. A Swiss critic called the last movement “perhaps the greatest Adagio written since Beethoven.” And a critic writing for the AMZ enthused, “the Adagio rises to heights which situate this movement among the most sublime in all symphonic literature.” At the premiere, Mahler was called back to the podium 12 times, and the local newspaper reported “a thunderous ovation lasting no less than fifteen minutes.” In conversation with Jean Sibelius, Gustav Mahler proudly declared, “A Symphony must be like the world—it must contain everything.” In his third symphonic essay, Mahler created a towering monument to Nature that encapsulated the history of the entire universe.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 3 – I. Kräftig, Entschieden

Gustav Mahler, 1898

According to a letter penned to his friend Friedrich Löhr, “the new work was a grand, musical evocation of the forces and creations of Nature.” Mahler initially struggled to find an appropriate title for this work, suggesting, “Das glückliche Leben” (The happy Life), “Die fröhliche Wissenschaft” (The Joyful Science) but eventually settled on the picturesque “Ein Sommermorgenstraum” (A Summer Morning’s Dream). In addition, individual movements bore the following titles:

1. “Pan erwacht. Der Sommer marschiert ein” (Pan Awakens – Summer Marches In)

2. “Was mir die Blumen auf der Wiese erzählen” (What the Flowers and Meadows Tell Me)

3. “Was mir die Tiere im Wald erzählen” (What the Animals of the Forest Tell Me)

4. “Was mir die Nacht (der Mensch) erzählt” (What the Night (Man) Tells Me)

5. “Was mir dir Morgenglocken (Engel) erzählen” (What the Morning Bells (Angels) Tell Me

6. “Was mir die Liebe erzählt” (What Love Tells Me)

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 3 – II. Tempo di menuetto, Sehr mässig (Michaela Schuster, alto; Cologne Cathedral Children’s Choir; Cologne Opera Chorus; Cologne Gürzenich Orchestra; Markus Stenz, cond.)

Mahler’s Komponierhäuschen

Originally, there was to be a seventh movement with the title “Was mir das Kind erzählt” (What the Child Tells Me), but this was eventually dropped to become the last movement of his 4th Symphony. As had become customary with Mahler, he expunged all programmatic indications from the score prior to its first publication in 1898. Confiding in his mistress Anna von Mildenburg in 1896, Mahler suggested that, “my symphony is going to be something the likes of which the world has not yet heard. All nature is voiced therein, and it tells of deeply mysterious matters and feelings.”

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 3 – III. Comodo, Scherzando, Ohne Hast (Sofia Philharmonic Orchestra; Emil Tabakov, cond.)

Steinbach piano in Mahler’s Komponierhäuschen

During summertime, Gustav Mahler would habitually take refuge from his extensive conducting responsibilities by withdrawing to the Austrian Alps. In 1893, he discovered the village of Steinbach on the Attersee, located in the breathtakingly beautiful Salzkammergut region of Upper Austria. In an isolated cottage on the shore—which Mahler affectionately called his “Komponierhäuschen” (composing hut) —he would reconnect with nature and the sources of his inspiration. Above all, it provided him with the solitude and seclusion that ultimately stimulated his compositional activities. According to Bruno Walter, Mahler followed a strict daily regiment. “He spent his mornings at work in the cottage, undisturbed by the noises of the house. He went there at six in the morning, at seven his breakfast was silently placed before him, and only when he opened the door at noon would he return to normal life.”

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 3 – IV. Sehr langsam, Misterioso (Waltraud Meier, mezzo-soprano; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Klaus Tennstedt, cond.)

This enormous hymn to the natural world unfolds contrary to the expected manner of a conventional symphony. Rather than building cohesion through musical material that cyclically returns in subsequent movements, Mahler projects an epic journey through a hierarchical universe. He envisaged an evolutionary ladder that begins with the creation of the universe, and reaches its climax in the love of God. In between, the symphony represents the “stages of being,” from vegetable and animal life, through mankind and the angels.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 3 – V. Lustig im Tempo und keck im Ausdruck (Agnes Baltsa, mezzo-soprano; Vienna State Opera Chorus; Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Lorin Maazel, cond.)

Anna von Mildenburg

Although controversy still rages as to Mahler’s suggested division of the symphony into two parts, it is undeniable that the composer not only created his longest and most expansive work, but also one that is remarkably free of nightmares and apocalyptic visions. In fact, the concluding “Adagio” is Mahler’s vehicle for “the most profound expressions of reverence and spiritual devotion.” Full of eloquence, comfort and grace, the movement unfolds as a set of variations, unrelentingly building towards the eternal home of spiritual love that Mahler valued so highly. For what is best in music, Mahler once remarked, “is not to be found in the notes.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 3 – VI. Langsam, Ruhevoll, Empfunden