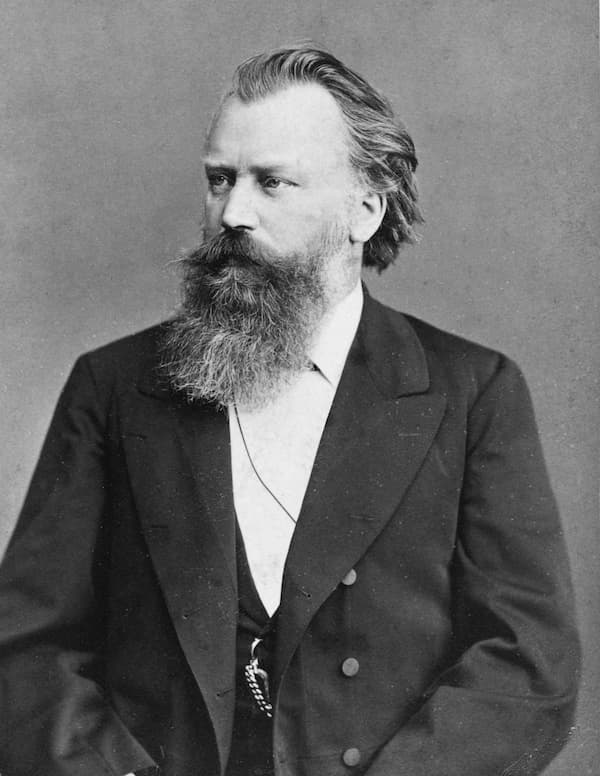

Josef Kriehuber: Berlioz (1845) (Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Musique)

Picking unpublished poems from the manuscripts of his neighbor romantic poet and writer Théophile Gautier, Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) created his song group (not a cycle) Les nuits d’été (The Nights of Summer).

Completed in 1841, the songs, written for mezzo or tenor and piano, were dedicated to the opera composer Louise Bertin, who also knew Berlioz through his writing work for her father, editor of the Journal des débats. In 1843, Berlioz orchestrated the fourth song for his mistress, the mezzo singer Marie Recio. Finally, by 1856, at the suggestion of his publisher, the other songs were orchestrated as well and dedicated to a variety of people.

The first song, Villanelle, was given the title ‘Villanelle rhythmique,’ by Gautier, but it was shortened by Berlioz. It’s a celebration of spring, the arrival of the flowers, the return of the birds, and walking around enjoying the season for lovers. The orchestrated song was dedicated to Louise Wolf, Chamber Singer to the Archduchy of Weimar, where Liszt had been instrumental in getting Berlioz’ music performed.

Hector Berlioz: Les nuits d’été (The Nights of Summer), Op. 7 – Villanelle (Elsa Maurus, mezzo-soperano; Lille National Orchestra; Jean-Claude Casadesus, cond.)

The second poem, Le spectre de la rose, is about the ghost of a rose that was carried by a young girl at a ball. She killed the rose by picking it, but it declares that its death was one that even kings would be jealous of because it was worn by HER. The story was memorably made into a ballet by Fokine in 1911 and was danced by Nijinsky as the rose.

Hector Berlioz: Les nuits d’été (The Nights of Summer), Op. 7 – Le spectre de la rose (The Spectre of the Rose) (Elsa Maurus, mezzo-soperano; Lille National Orchestra; Jean-Claude Casadesus, cond.)

Poster for the Ballet Russes, 1911,

Nijinsky as drawn by Jean Cocteau

Although celebrating the nights of summer, these are not happy cheery songs. The three central songs, No. 3, Sur les lagunes: Lamento (On the Lagoons: Lamento), no. 4, Absence, and no. 5, Au cimetiere: Clair de lune (At the Cemetery: Moonlight) deal with death and after. Through the whole work, the subject is love: from its innocent beginning in Villanelle, through courtship in Le spectre de la rose, and even death and burial (songs three through five).

The final song, however, changes everything. We are on a boat to wherever the ‘young beauty,’ presumably the dead lover, wishes to go – Norway or Java? She wishes to go to the faithful shore where one loves forever…unfortunately, ‘that shore…is almost unknown in the land of love.’ This isn’t the boat piloted by Charon across the river Styx, but something much less dark – one has the sense of blue skies and blue seas. The desire of the young woman / young soul for eternal love is not to be found in this world or any other, by implication.

Gautier’s original title was ‘Barcarolle’ referring to the traditional song sung by the Venetian gondoliers and we hear that water in the music.

Hector Berlioz: Les nuits d’été (The Nights of Summer), Op. 7 – L’ile inconnue (The Unknown Island) (Elsa Maurus, mezzo-soperano; Lille National Orchestra; Jean-Claude Casadesus, cond.)

Martinet: Harriet Smithson as Ophelia in Hamlet (ca. 1827) (Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Musique)

Les nuits d’été puts together otherwise unconnected poems. Gautier did not intend them as a cycle, but they were chosen and put together as a group by Berlioz. They give us love, but after the first song, it’s not love in the romantic sense (except for the heroine dying young, perhaps). We could look at Berlioz’ home life for some clue.

Berlioz was not in a happy situation in his home life – his wife, the former Shakespearean actress Harriet Smithson, resented his rise to fame as hers fell, and as her health failed, she took up alcohol as a remedy.

Berlioz found love with his mistress Marie Recio, to whom the orchestrated 4th song is dedicated. Smithson and Berlioz separated in 1843 and Berlioz moved in with Recio in central Paris while Smithson stayed in Montmartre.

As always, Berlioz presents us with the unusual – love songs that end in death and a dead soul that cannot achieve what it truly wants.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter