Pierre Boulez

Probably the most important 20th century French composer of the avant-garde, Pierre Boulez was born on 26 March 1925 in Montbrison, a small town in the Loire department to Léon and Marcelle (née Calabre) Boulez. He tirelessly worked on behalf of contemporary music, and through force of will and ruthless combativeness, secured his position at the head of the Parisian musical avant-garde. For Boulez, his predecessors had simply not been radical enough, and he was calling for a renewed modernism. His father was an engineer and technical director of a steel factory, and by all accounts a severely authoritative figure. In contrast, his mother was describes as “an outgoing, good-humored woman, who deferred to her husband’s strict Catholic beliefs, while not necessarily sharing them.” The family, also including older sister Jeanne and a younger brother Roger, lived comfortably in an apartment above a pharmacy. Scholars report that as a boy, “Boulez divided his attention between music and mathematics. He sang in the choir of his Catholic school at St Etienne, and he enjoyed playing the piano; but his early aptitude for mathematics marked him out—at least in the eyes of his father—for a career in engineering.”

Pierre Boulez: Piano Sonata No. 2

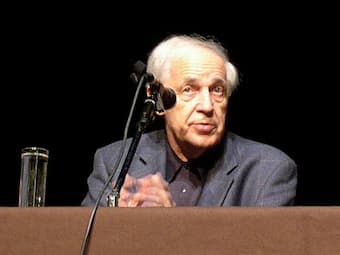

Pierre Boulez, 2004

From the age of seven, Boulez went to school at the Institute Victor de Parade, a Catholic seminary. He took piano lesson and played chamber music with local amateurs, but soon took classes in advanced mathematics at the Cours Sogno in Lyon. He did see his first operas and made the acquaintance of the well-known soprano Ninon Vallin, who persuaded Boulez’s parents to allow him to apply to the Conservatoire de Lyon. Boulez was rejected, but more than ever he was determined to pursue a career in music. Against the expressed wishes of his father he moved to Paris hoping to enroll at the Paris Conservatoire rather than de Ecole Polytechnique. In October 1943 he auditioned but failed the pianists’ entrance examination. Boulez was nevertheless admitted in January 1944 to the preparatory harmony class of Georges Dandelot, and he made good progress.

Pierre Boulez: Structures Livre 1, for two pianos

Andrée Vaurabourg

Privately, Boulez started to take counterpoint lessons with Andrée Vaurabourg, the wife of the composer Arthur Honegger. She remembered him as an exceptional student, and by June 1944 Boulez approached Olivier Messiaen, who wrote in his diary, “Likes modern music. Wants to study harmony with me from now on.”

Olivier Messiaen with Boulez, 1988

His advanced harmony lessons with Messiaen decisively shaped Boulez’s musical vision. For one, Messiaen introduced his students to medieval music and the music of Asia and Africa. Yet, Boulez also knew that he had to further explore the 12-tone method introduced by Schoenberg a generation before. “I had to learn about that music, to find out how it was made. It was a revelation—music of our time, a language with unlimited possibilities. No other language was possible. It was the most radical revolution since Monteverdi. Suddenly, all our familiar notions were abolished. Music moved out of the world of Newton and into the world of Einstein.” In June 1945, Boulez took a premier prix at the Conservatoire, and he was described as “the most gifted—a composer.”

Pierre Boulez: Pli selon pli – No. 2. Improvisation sur Mallarme I (Christine Schäfer, soprano; Ensemble InterContemporain; Pierre Boulez, cond.)

Grande salle Pierre Boulez, Paris Philharmonie

Boulez was particularly interested in Balinese and Japanese music, and African drumming at the Musée Guimet and the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. He once explained, “I almost chose the career of an ethnomusicologist because I was so fascinated by that music. It gives a different feeling of time.” Looking to enrich the European sound vocabulary, “many listeners first impression of Furious Artisans is primarily exotic; and in fact my use of xylophone, vibraphone, guitar, and percussion is very different from the practice of Western chamber music… the xylophone representing the African balafron, the vibraphone the Balinese gender, and the guitar recalling the Japanese koto.” Boulez stormed on the avant-garde scene with his provocative 1951 article “Schoenberg is dead,” in which he accused the older composer of not having pursued the serial system to its logical conclusion by excluding rhythm and form. Boulez’s answer emerged in his earliest uncontested masterpiece, Le Marteau Sans Maître for voice and ensemble, a work Stravinsky described as “one of the few significant works of the postwar period of exploration.” Boulez’s music remains essentially unemotional on the surface but is infused with brilliant color and rhythmic discipline that extends from a gentle lyricism to a furious expressionism.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Pierre Boulez: La Marteau Sans Maître, Part 1