Berndardo Strozzi: Claudio Monteverdi (ca. 1630)

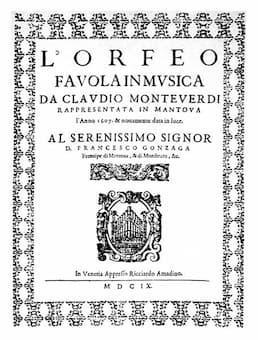

Commissioned for the 1606/7 Carnival season, Monteverdi’s first opera L’Orfeo was performed in Mantua on 24 February 1607. Essentially, it was commissioned by Francesco Gonzaga in competition with his brother Ferdinando Gonzaga, both sons of the Duke of Mantua. Claudio Monteverdi was employed at the Gonzaga court for 16 years as a performer and arranger of stage music. Tasked with providing Carnival entertainment, Monteverdi constructed his first opera score by “blended existing musical styles into a unity that was entirely new.”

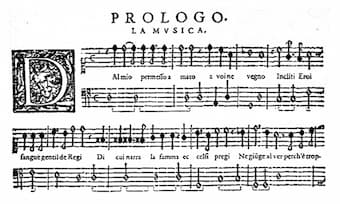

Prologue of Monteverdi’s opera L’Orfeo

A musicologist writes, “the score full of arias, strophic songs, recitatives, choruses, dances, and dramatic interludes is based on precedents, but it reaches complete maturity in that recently developed form … Here are words as directly expressed in music as the pioneers of opera wanted them expressed; here is music expressing them … with the full inspiration of genius.” The work was first performed in the ducal palace, and the Duke immediately ordered a second performance on 1 March.

Claudio Monteverdi: L’Orfeo “Act I, Prologue”

Ducal Palace of Mantua

This score of great dramatic power and lively orchestration was highly praised and published in Venice in 1609, with performances recorded in Salzburg as early as 1614 and 1619. Thereafter, L’Orfeo appears to have been unperformed until the early years of the 20th century. The first edition for a modern performance was published by Vincent d’Indy in 1905, and it had to address some basic problems. Monteverdi had indicated the orchestral requirements at the beginning of his published score, “but in accordance with the practice of the day he does not specify their exact usage…decisions were made based on the orchestral forces at their disposal.” In addition, singers would have been allowed to embellish their arias. As such, modern editions of L’Orfeo fall into two distinct categories. We find free adaptations or modern arrangements of the original, which include versions by d’Indy, Orff, Respighi, Maderna, and Berio. The second “kind of edition and performance is informed by research into performance conventions of Monteverdi’s own time,” and include versions by Malipiero and Hindemith, with scholar-performers like Raymond Leppard, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Roger Norrington, and John Eliot Gardiner also attempting to provide an authentic presentation of the musical aspects of Monteverdi’s work.

Monteverdi: L’Orfeo (Act II excerpt)

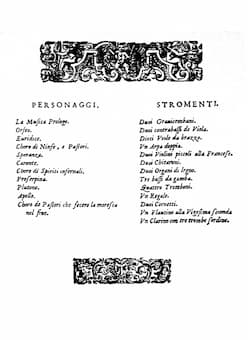

Lists of character and instruments for L’Orfeo

The libretto was fashioned by the young lawyer and career diplomat Alessandro Striggio, who was himself a talented musician. Striggio primarily relied on Books 10 and 11 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Book Four of Virgil’s Georgics. While these passages provided him with the basic material, Striggio still had to structure the staged drama. Apparently, he drew on the play Il pastor fido, and on Ottavio Rinuccini’s libretto for Peri’s Euridice. In the event, L’Orfeo is divided into a prologue and five acts, “a division which relates it to classical tragedy, and it was almost certainly played without breaks between the acts.” The action takes place in two contrasting locations: the fields of Thrace (acts 1, 2 and 5) and the Underworld (acts 3 and 4). The opera is prefaced by an instrumental toccata and followed by the entrance of “La musica,” the spirit of music. What follows is the story of the Greek legend of Orpheus, his descent to Hades, and his fruitless attempt to bring his dead bride Eurydice back to the world of the living.

Monteverdi: L’Orfeo, “Tu se’ morta”

Title page of L’Orfeo

Orpheus was not only the legendary hero of Greek mythology; he was also the first superstar musician. Endowed with superhuman musical skills, he was nevertheless a flawed and arrogant mortal, who sincerely believed that he could cheat death. And it was that juxtaposition of weakness, insecurity and charisma that prompted Monteverdi to probe human nature and desire by means of music. “The fact that music is capable of fluid, imperceptible change and harmonic modulation gives it the facility to straddle one realm of existence and the next.” Monteverdi composed L’Orfeo under the shadow of his wife’s death in 1607. Experiencing intense grief and despair, his emotional state mirrored the circumstances of the Orpheus of Greek mythology, “who suffers, loves, exults, mourns, goes on a heroic rescue mission, stumbles at the last hurdle and finally reaches a new and deeper understanding of himself.” Monteverdi called his creation a “favola in musica,” simply indicating that all actors are singing their parts. And while Monteverdi might be surprised to find himself hailed as the inventor of the opera, L’Orfeo is a radically innovative and extraordinary work. Whether we should reasonably call him the “creator of modern music” is a matter of semantics. What is undisputed is the fact that Monteverdi developed powerful ways of expressing and structuring musical drama.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Monteverdi: L’Orfeo, “Possente spirto”