Roman mosaic floor from Palermo depicting Orpheus

Claudio Monteverdi’s 1607 opera L’Orfeo wasn’t the first opera, Jacopo Peri’s Dafne (1598) bears that honour. However, L’Orfeo is the earliest opera that is still on our opera stages, and for an opera to hold our attention for over 400 years says a great deal about Monteverdi’s work.

What it starts with immediately grabs our attention. It’s called a ‘toccata,’ which in publications from the 1590s are keyboard compositions that require each hand in sequence to play virtuosic runs and passages against chords in the other hand. A less common use of the word is for music for multiple instruments and that’s how Monteverdi uses it here.

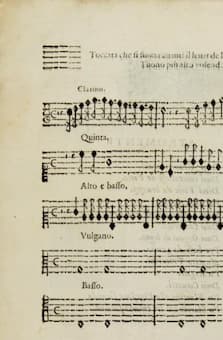

He specifies these instruments: Clarino, Quinta, Alto e basso, Vulgano. Basso.

Monteverdi’s instrumentation for the Toccata (1609)

Through the entire opera, Monteverdi specifies some 41 instruments to be used, each depicting a particular scene. When we’re on the surface, strings, recorders and harpsichord represent the landscape of Thrace while Orfeo’s visit to the underworld involves the brass. In the Toccata, all of the instruments are trumpets of varying lengths – from the shortest and highest, the clarino, to the bass trumpet. He specifies that the highest trumpet, the clarino, should be played with a mute. The ‘vulgano’ would have been an organ (in the instrument list he specifies an organ made of wood) and the basso would be for the basso continuo.

The performance directions, in addition to the note about the mute, say that the Toccata should be played three times. The Toccata was common at the court of Mantua to signal the start of performances. Monteverdi’s 1610 Vespers begins with the same toccata.

The problem is that many performers don’t find the Toccata flamboyant enough and start to meddle with it. We’ll start with a relatively plain version:

Claudio Monteverdi: L’Orfeo – Toccata (Concentus Musicus Wien; Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond.)

And another, done as a procession growing ever nearer:

Claudio Monteverdi: L’Orfeo – Toccata (Taverner Players; Andrew Parrott, cond.)

If we reexamine the title of the work, Toccata, we can relate it to an English word, tucket, dating from 1593. Tucket is found in William Shakespeare’s plays such as King Lear (1606) and refers to both sounding a trumpet or beating a drum, with the intent of what we would now call a fanfare. This may be why other versions of the L’Orfeo Toccata, particularly from English ensembles, are played with the addition of other instruments.

This version adds a long percussion introduction:

Claudio Monteverdi: L’Orfeo – Toccata (Les Arts Florissants; Williams Christie, cond.)

Here are 4 versions that add percussion and even strings, often with a contrasting middle section:

Claudio Monteverdi: L’Orfeo – Toccata (English Baroque Soloists; John Eliot Gardiner, cond.)

Claudio Monteverdi: L’Orfeo – Toccata (Hamburger Bläserkreis für Alte Musik; Camerata Academica; Jürgen Jürgens, cond.)

Claudio Monteverdi: L’Orfeo – Toccata (Les Sacqueboutiers; Le Concert d’Astrée; Emmanuelle Haïm, cond.)

Claudio Monteverdi: L’Orfeo – Toccata (London Baroque; London Cornett and Sackbut Ensemble; Charles Medlam, cond.)

And this last one not only adds drums but also flourishes to the clarino line:

Claudio Monteverdi: L’Orfeo – Toccata (San Petronio Cappella Musicale Orchestra; Sergio Vartolo, cond.)

What do we think of these versions of Monteverdi’s Toccata? His directions to play the music three times is clear enough and each of the recordings does that. It’s all the other stuff that gets added that may be unnecessary. If Monteverdi’s use of low brass for the underworld and strings and winds for the upperworld is deliberate, are we muddying his ideas by doing versions of the Toccata with those other instruments added?

Interpretation is always in the ear of the beholder – it’s often valuable, though, to compare different versions to see how their directors interpreted what the composer said (or may not have said). As you’ll see in the image above, Monteverdi did not specify what the organ and the basso continuo were supposed to be playing above their notes – that would have been their own interpretations as well.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter