Xu Zhong © Shu Xiaoning

Once upon a time, Shanghai was a small fishing village on the Yangzi River delta. By the mid-19th century, however, the village turned into a city administered concurrently by the British, Americans and French. Each colonial presence brought its particular culture, architecture and societal conventions. Shanghai had its own walled Chinese city, and this prodigious mix of cultures turned Shanghai into an important industrial center and trading port. The territory of the French Concession was established on 6 April 1849 and significantly expanded in 1899. It featured stunning arts venues, magnificent architecture, the best restaurants, and the strongest international business connections. The city quickly became known around the world as the Paris of the East. Today, Shanghai is once again one of China’s most vibrant cities. Not only is Shanghai the country’s commercial headquarters, but it is one of the most culturally active and vibrant locations on the planet.

Shanghai Grand Theatre © Wikipedia

Then as now, beauty and charm have coexisted alongside commercialism and art. Colonial architecture and neon-lit skyscrapers stand side by side and underscore the fact that Shanghai is a city of contrasts and of change. The city is home to some of the most spectacular performing venues around the word, and that includes the Shanghai Grand Theatre. It is one of the largest and best-equipped stages in the world, and it opened its door on 27 August 1998. This stunning piece of architecture was the brainchild of French architect Jean-Marie Charpentier (1939-2010), grandnephew of famed composer Gustave Charpentier. The architect and urban planner established a dedicated agency in Paris in 1969, and in 1984 he was one of the first European architects to permanently settle in China. The Shanghai Grand Theatre is his masterwork, and the whole building is a crystal-like palace consisting of three main theatres and supporting facilities. The venue has staged over 6,000 performances of various genres, including Western classical music, spoken dramas and Chinese opera.

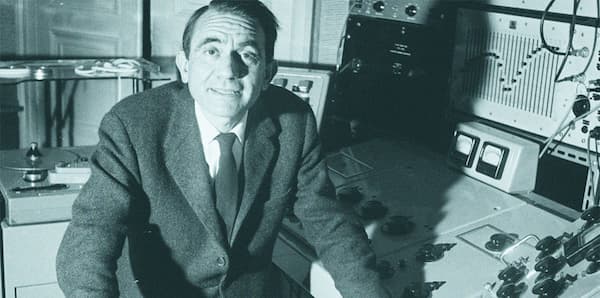

The Shanghai Grand Theater has actively featured a multitude of domestic and foreign performing arts productions. One of the most prominently featured companies is the “Shanghai Opera House.” The chief conductor and president of this venerable western-style opera company is Maestro Xu Zhong, who grew up in Shanghai and furthered his studies in Paris. He started his piano studies at the age of 3, and has since won numerous prestigious international competitions. Prizes and honours include the First Prize at the Maria Canals International Piano Competition (1988), the Second Prize at the Hamamatsu International Piano Competition (1991), the First Prize at the Santander Paloma O’Shea International Piano Competition (1992), the First Prize and additional five awards at the Tokyo International Piano Competition (1992), and the Fourth Prize at the Tchaikovsky International Piano Competition in Moscow (1994).

Haifa Symphony Orchestra Zhong Xu Piano & Conductor

Mozart Piano Concerto No. 9 – 2nd Movement

Xu Zhong’s stellar artistic experiences as a pianist and conductor are complemented by his administrative involvement in leading arts organizations abroad and in Shanghai. He was the Artistic Director of “French Culture in Shanghai,” and he is the Founder and Artistic Director of Shanghai International Piano Competition. He was Artistic Consultant of China Shanghai International Arts Festival, and Xu Zhong was nominated as Music Consultant of Shanghai Concert Hall, member of Shanghai Grand Theatre Arts Group Artistic Committee and Vice President of Shanghai Oriental Art Centre Arts Committee. And as I have mentioned previously, he is the president of the Shanghai Opera House. In today’s extraordinary concert, Maestro Xu Zhong leads the Suzhou Symphony Orchestra in a performance of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 and No. 4. We are delighted that Maestro Xu Zhong has agreed to share his thoughts on this particular event.

You grew up in the Paris of the East and later studied in the Paris of the West. Experiencing both cultures firsthand, how has this shaped you as a person and as an artist?

Xu Zhong and the Suzhou Symphony Orchestra © Suzhou Symphony Orchestra

Indeed, a real Paris and a Paris in the East! When I was young, I learnt about France in novels by Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas. Once a French concession, Shanghai still preserves a lot of French architectures. I started to learn the piano at the age of 3 and subsequently entered the affiliated secondary school of the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. In 1986, I received financial support to study at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris.

I had a very complete music education in both cities. In Shanghai I found my passion for the piano, which I further developed under Dominique Merlet and Philippe Entremont in Paris. I also discovered my love for conducting and a passion for vocal music, thanks to my excellent teacher Michel Piquemal. In fact, my career begins with the piano and gradually opened up into many different fields. And that includes my most challenge appointment as the Artistic Director in an Italian opera house. I had to plan the season, the tour, the recording session, as well as conducting the orchestra. Also, I had to choose the stage director and give comments on the stage setting. In Shanghai, I was appointed to lead the cultural session of “French Culture in Shanghai,” and simultaneously, French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing praised me as “the best interpreter of French music.”

In tonight’s concert you are once again in charge of the freshly minted Suzhou Symphony Orchestra. What are the challenges of performing Mahler with a relatively young orchestra?

The Suzhou Symphony Orchestra is a relatively young orchestra. Of course, in taking on monumental works of classical music, young orchestras face many challenges compared with those orchestras that have a long history. However, I think no matter which orchestra or conductor it is, it must feel like “walking on thin ice” in facing musical giants such as Beethoven and Mahler. Familiarity with the music and mastery of techniques can be relatively easy, however one need also to feel, to understand and to keep exploring the profound meaning underneath the notes.

I think that a young orchestra actually has certain advantages in taking on such monumental works. We usually pay a lot attention to Mahler’s “life and death.” But what we need to understand is how much hope and desire for the future is reflected in all that desperation. This is like Tai Chi, where there is YIN, there is YANG, mutually reinforcing and neutralising each other. The youthful atmosphere of a young orchestra, and its enthusiasm and vitality can balance the sad and pessimistic aspects in Mahler’s works. Of course, the musicians of the orchestra prepare for this concert with great respect and humility, which I am very happy to see. This is the attitude that the young people must adopt in facing these monumental works of greatness.

As the chief conductor of the Suzhou Symphony Orchestra you have decidedly contributed to its artistic and professional development and growth. What are some of the highlights of this collaboration?

In 2017, I led the Suzhou Symphony Orchestra to tour abroad for the first time, and we performed Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 and the concert version of the opera “Aida” in Dieuze (France) and Saarbrücken (Germany) to great acclaim. In October of the same year, I conducted six consecutive performances of “Aida” with the Suzhou Symphony Orchestra at the Hong Kong Cultural Arts Centre. In fact, “Aida” was a very important project during the first year of the establishment of the orchestra. In 2018 we toured Suntory Concert Hall in Tokyo, the Kobe International Hall, and the NTCH Concert Hall in Taipei, were we performed concerts that featured both Chinese and Western repertoires.

In July 2019, in order to allow local Jiangsu culture to go abroad, and to promote Chinese cultural brands abroad—to showcase the spirit of humanism and charm of China on the international stage—I led the Suzhou Symphony Orchestra in a performance of the Chinese original opera “The Diaries of John Rabes” (a production of the Jiangsu Grand Theatre) at the Berlin State Opera, the Elbe Philharmonic in Hamburg and the Ronacher Theater in Vienna.

Since the establishment of the orchestra, the Suzhou Symphony Orchestra has successfully held a large-scale international piano competition and a composition competition. I am very honoured to be the artistic director of the Suzhou Jinji Lake Piano Competition. Especially as a pianist, I very much hope to do a good job in discovering the future stars of classical music for the next generation and create better conditions for them to perform on the international stage. I also conducted the concert of the Suzhou Jinji Lake Composition Competition. I think artistic creation should not only look back at the past, but also needs to be based on contemporary subjects. To explore realistic themes and to reflect the characteristics of our times through art is, in my simple and humble opinion, the responsibility of every art practitioner.

As a conductor, how do you approach the highly personal and remarkably diverse musical universe of Gustav Mahler?

Xu Zhong and the Suzhou Symphony Orchestra © Suzhou Symphony Orchestra

I want to talk about this on three different levels. First, there is Mahler’s personal taste of art, then his personal life, and finally his artistic creation. Mahler had a very refined taste in art, especially influenced by literature. He also developed a keen interest in the East. For most people, when we think about composers influenced by the East or China, we often think of Debussy. But there had been important and in-depth German research on classical Chinese literature, history and philosophy as well. Mahler’s “Das Lied von der Erde” is inspired by Tang poems, and the German romantic poet Friedrich Rückert, a professor of Oriental languages, influences his “Rückertlieder” and “Kindertotenlieder.”

This brings me to the second aspect, Mahler’s personal life. We can hear themes related to death and helplessness in Mahler’s works. Especially the death of his daughter was a terrifying blow to him. I am also a father myself, so I understand the sadness in Mahler’s music very well. Not to mention the confusion and hesitation caused by his “triple homelessness.” We can also find the love and hope he tried to convey through his music, and the spirit of longing for salvation in despair. Mahler is a very complicated and extremely tangled person, and his life was full of tragedies and contradictions.

The third aspect, besides being a composer, Mahler was actually a very good opera conductor. Although he didn’t compose any operas, we can find many references to literature and music in his works, such as the aforementioned art songs. He also embedded vocal movements in his symphonies, such as Symphony No. 3 and Symphony No. 4, not to mention the Symphony No. 8, which has “Thousand People” performing together. Therefore, in his process of symphonic creation, Mahler integrated vocal conventions and looked towards folk songs for inspiration.

MAHLER: SYMPHONY NO. 1

It all began in the small village of Kalischt—presently located in the Czech Republic—where Gustav Mahler was born to an aspiring tavern proprietor and a soap-maker’s daughter in 1860. The family quickly moved to Iglau, a thriving military and trade center within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and became part of a flourishing German-speaking Jewish community. Gustav’s father established a distillery and tavern business, and the family secured lodgings right above the pub. Growing up, the young Mahler was exposed to an infinite variety of music from all periods of history and every corner of the Empire. Iglau was home to an amateur orchestra, a professional theatre, an opera and the church of St. Jakob, each richly contributing to the musical life of the community. In addition, Gustav experienced a wide range of music from local and extended folk traditions, that including characteristic dances and songs of Jewish, Moravian, Czech, Austrian, German and Bohemian origins. Since Iglau was also a major staging point for the Austrian army, colourful military bands regularly participated in local festivals and engaged in concert activities. The memories of these musical impressions—alongside the stunning natural beauty of the Moravian countryside—would haunt Mahler for the rest of his life and dynamically reverberate in his compositions.

Mahler initially conceived of his first Symphony as a “Symphonic poem in two parts,” encompassing a total of five movements. The work received its devastating premiere in Budapest on 20 November 1889. Greeted by animosity, indifference, bewilderment and rejection, Mahler’s first symphony not only represents a highly personal and conceptual musical exploration, but it also was squarely placed within an exceedingly volatile musical environment. Stunned by the severe reaction of the Budapest audience, Mahler quickly re-titled his composition “Titan” eine Tondichtung in Symphonieform (“Titan” a tone poem in symphonic form). He also appended titles to individual movements, and audiences were treated to a descriptive programme in which Mahler detailed the metaphorical content of each movement. Programmatic explanations did not alleviate the continued hostile reactions, and in its final form Mahler suppressed the titles, expunged the programmatic explanations and rejected the tone poem in favour of the symphony.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 1 – I. Langsam, schleppend (Bavarian State Orchestra; Bruno Walter, cond.)

As a conductor, how do you approach the autobiographical and highly personal aspects of Mahler’s 1st Symphony?

Shanghai Grand Theatre at night © SmartShanghai.com

It should be said that artistic creation must be closely related to an artist’s own life and experience, and Mahler is no exception. One thing I find interesting is that many composers possess one or two relatively strong cultural foundations. Mahler’s “triple homelessness” status and his life are all reflected in his works by different music themes and styles. Take the example of his Symphony No. 1. It contains a multitude of themes—especially the familiar Bohemian folk songs in the fourth movement—that are deeply rooted in Mahler’s life experience.

The creation of the Symphony No. 1 was also inspired by a caricature, but the work itself is actually a fairy tale. I even think that its satirical style is similar to the dark fairy tales of European literature. If you compare the musical language of this work with other works rooted in fairy tales and the mysterious aspects of nature, such as Prokofiev’s “Peter and the Wolf,” or Tchaikovsky’s “The Nutcracker,” you can see the uniqueness of Mahler’s personal style.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 1 in D Major, “Titan” – IV. Stürmisch bewegt (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Roger Norrington, cond.)

Mahler’s 1st symphony started as a tone poem and ended up as a symphony. What did Mahler gain, or alternately disguise, by transferring the work from a programmatic context into the realm of absolute music?

The first two movements of Mahler’s Symphony No.1 are relatively clearly structured sonata movements. Therefore, according to historical records, at the debut of this work in Budapest, the audience found the first and second movements very acceptable. The third movement, known as the famous “The Marching of the Funeral Procession” derived from a folk song, was not quite successful. That is surprising, as the funeral-march theme is rather common in symphonic music; just think of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3.

Usually, we find a scherzo as the third movement of a symphony. If we consider the 3rd movement of Mahler’s Symphony No.1 a scherzo, it still makes sense. In fact, for today’s audience, this movement may be one of Mahler’s most widely known and talked-about music, but why it was a failure back in the old days of Mahler? I think that’s a very interesting phenomenon that needs to be further explored.

Mahler gave titles to all these movements, but in the end he removed them to avoid too much guidance for the audience. I think in addition to the titles themselves, there are also cuckoo motives, the citing of melodies from several songs, and the portrayal of the devil from the poem “Titan,” which gave the work its original title. But from the perspective of a larger structure, Mahler composed a very clear symphonic trajectory. Even without programmatic titles, it is still a very successful work.

I think there is an additional phenomenon in that Mahler likes to use the element of titled music in untitled works, and he uses symphonic thinking in creating works such as art songs. I found that in Western culture, “conflict” and “contradiction” are usually used to describe such practices, and this phenomenon is referred to as “binary opposition.” In Eastern culture and philosophy, this juxtaposition of combining opposing ideas is considered harmonious as Yin generates Yang, while Yang generates Yin. I think Mahler’s understanding of the East is not only reflected in his use of Tang poetry in “Das Lied von der Erde,” but that the philosophy of Yin and Yang had a great impact on his compositions throughout.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 1 in D Major – III. Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen (South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden; Michael Gielen, cond.)

This symphony, as Mahler explained to Sigmund Freud, contains a compendium of musical memories that are provocatively, and often jarringly, juxtaposed. How can you musically communicate this far-reaching eclecticism to your audience?

Yes, if you look at the musical materials one by one, they do have their own features and independence in terms of musical image and musical atmosphere. As you said, when these paragraphs are juxtaposed it has a great impact, creating a kind of disharmony. But this is also the most fascinating part of this work: it seems to tell a twisting story. So for the conductor, how to communicate these twisting images clearly to the audience? My approach is to adjust the speed. Imagine you are telling a story, what would you do when you say the words “suddenly” and “but”? Maybe you will take a good breath at the end of the previous sentence, or lower your voice and slow down. In other words, the presentation of new materials cannot be sudden, but it must be prepared.

Music functions in much of the same way, and audiences, even without the guidance of fancy titles, can still understand the composer’s intentions alongside the flow of the music.

MAHLER: SYMPHONY NO. 4

The folksong qualities and disarming sincerity of the Wunderhorn lyrics offered Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) the possibility of inventing a new type of Lied. Attracted by the simplicity and musicality inherent in the texts, Mahler composed diatonic and direct settings that reflected the hint of sophistication that, in part, stimulated the compilation of the anthology in the first place. Supported by an orchestral accompaniment that was economical in terms of size and scoring, Mahler created a chamber-like quality that not only proved fundamental to his own musical development, but also decisively influenced the search for musical progress in the early twentieth century. Mahler’s integration of the Wunderhorn songs into the symphonic oeuvre blurred the distinction between the narrative and the dramatic, and served him as a referential guideline for structurally formulating his symphonic thoughts.

Mahler famously described his 4th symphony as representing the sky, “whose uniform blue occasionally darkens yet always reemerges fresh and renewed.” The composer employed a slimmed-down orchestration—omitting trombones and tubas—and a reduced number of horns, trumpets, woodwinds and strings, communicating an essentially playful and serene musical character. This outward simplicity, however, belies a thoroughly complex inner ferocity. Musically juxtaposing innocence and danger, youth and mortality, serenity and menace, Mahler created a symphony that explored the road from experience to innocence, from complexity to simplicity, and from earthly life to heaven. Mahler had actually composed the finale for this symphony already 8 years earlier.

This meant, that he had to plan the symphonic narrative backwards, starting with the already existing Finale and composing preceding movements that thematically and aesthetically were to build on the musical and philosophical materials originating in the childlike vision of heaven. That fact was not lost on a rather hostile Viennese press. A critic, with typical anti-Semitic propensity complained, “this 4th Symphony has to be read from back to front, like a Hebrew bible.”

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 4 – IV. Sehr behaglich” (Corrine Curry, mezzo-soprano; Harold Farberman, cond.; London Symphony Orchestra)

Mahler’s infatuation with Wunderhorn texts culminated not only in a substantial variety of solo and orchestral Lieder, it also informed his symphonic conception. How did these poems structurally and emotionally aid the formulation of his symphonic thoughts?

The name Wunderhorn derives from a German folk song collection containing more than 700 songs. Many of the themes are about history and ancient legends of Germany, as well as philosophical thoughts and expressions. These stories strongly attracted Mahler. The melody of each song has national features, and they also contain the spirit and thoughts of Germany nationalism. Martial rhythms are an important feature throughout. Mahler composed his Wunderhorn lieder first for the piano and orchestrated them later. The rich orchestral colours impart this song collection with a great sense of mystery. Wunderhorn requires solid technical footing from the singer, as it features big ranges, complex rhythms, dynamic contrasts and emotional changes.

When Mahler composed an art song, he was keen to structure it in the form of a symphony. He employed a complicated and unique orchestration, strong dynamic changes and delicate and exquisite timbre, essentially transferring the art song into the symphonic realm. Similarly, when Mahler composed his symphonies, he incorporated a number of art songs, especially in the Symphony No. 2, No. 3 and No. 4.

Mahler describing his 4th symphony as “a uniform blue sky occasionally darkened by clouds.” As a conductor, how can you simultaneously express and communicate this juxtaposition of outward simplicity and inner ferocity?

Mahler’s original idea was to merge his first four symphonies into one series using the Symphony No. 4 as a conclusion. The Symphony No. 4 was inspired by Mahler’s art song collection Wunderhorn, which was also the source of the last movement “Life in Heaven.” It depicts the yearning for heaven, and also shows Mahler’s desire for a better future.

This work is different from his other compositions. Mahler used a flashback technique and took heaven as his primary focus. He first completed the fourth movement, and afterwards composed the first three movements. Through this work, Mahler tried to convey to the world his strong and mysterious feelings and love for nature, his infinite worries about the fate of mankind, and his yearning for a free and bright world. But behind this happiness and excitement, we can also spot a bit of unease, especially in the second movement. It describes the fear of death from the perspective of a child, and the musical atmosphere is dark and exaggerated. This may be related to Mahler’s own life, or it may be related to his experience of having to change his religious beliefs.

When dealing with this work, what I value the most is the grasp of the timbre of each instrument. Mahler arranged the sounds and timbres of various instruments in a superb way, so during the rehearsal, it is necessary to highlight the timbre of each instrument while maintaining the balance of each section to create the contradictory atmosphere. This is the most challenging part.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 4 in G Major – II. In gemächlicher Bewegung, ohne Hast (Jaap van Zweden, violin; Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

Mahler’s 4th symphony reverses the symphonic trajectory by progressing from experience to innocence, from complexity to simplicity, and from earthly life to heaven. In your musical interpretation, how do you clarify this reverse evolutionary path to your musicians and to the audience?

Xu Zhong © Shu Xiaoning

This work is also unique in terms of compositional techniques. The orchestration and structure are very delicate and exquisite. The orchestration adopts a small-scale orchestra including 3 flutes, without trombone and tuba. The harmony and texture is relatively simple, similar to a basic classical style.

I think understanding Mahler’s works can be very subjective, or we can say Mahler structured his composition in a way similar to creating a novel. Mahler’s life was difficult and rough, and his body and mind were strongly affected. He was not welcomed in his era, and he was not welcomed by society. But he still preserved his beliefs, maintained innocence and kept his simplicity. Mahler also yearned for a peaceful and beautiful life, portrayed in the picture of heaven from the perspective of an innocent child.

This work is the last symphony of Mahler’s early career, a period during which he was still cheerful and optimistic. Although we can find some tragic thoughts in his music, Mahler kept exploring the meaning of life through the beauty and hostility of the real world, and thus deepened his love for life and his courage for facing death. Therefore, when conducting this piece, I focus on Mahler’s exciting and smooth melodies, as they carry the philosophical questions, thoughts and emotions that deeply touch people’s hearts.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 4 in G Major – III. Ruhevoll, poco adagio (Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; Rafael Kubelík, cond.)