Gustav Mahler

For every composer, the first work of a series is a serious undertaking. For the composers who followed Beethoven, the symphony was a particularly daunting mountain. Gone were the days of a composer writing hundreds of symphonies: Haydn wrote 106, Mozart wrote 41, and Beethoven 9, but even through that progression, we see the increasing importance of the symphony. The works grow ever larger, the performing forces swell, until by the end, it was no longer enough for Beethoven to have a full symphony orchestra, he also required vocal soloists and a chorus to convey his musical vision.

Gustav Mahler started composition of his Symphony No. 1 in late 1887, completing it in March 1888. In its first performances, it was described as a ‘symphonic poem’, but Mahler always called it a symphony. The first movement begins with a slow introduction in a very minimalist fashion – slowly moving, held notes in the strings, and then the introduction of the woodwinds. Finally, we get a melody in the horns (02:00), a cuckoo sounds in the clarinet, and as things start to accelerate, finally a light theme emerges (04:00).

It’s a highly unusual beginning for a symphony.

Mahler: Symphony No. 1: I. Langsam, schleppend (Minnesota Orchestra; Osmo Vänskä, cond.)

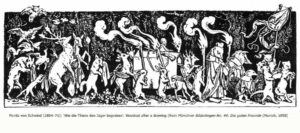

Schwind: The Huntsman’s Funeral

In looking at just this single movement, we can see the antecedents of the symphony: from Haydn he took the first movement sonata form, from Beethoven he took the slow introduction (Symphony No. 7) and the chordal opening (Symphony No. 9), and from Mozart, the graceful musical lines. However, the sound is pure Mahler, with its sections of solemnity changed by sections of pure joy. Nature comes with the cuckoo, which also appears In Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, but, unlike Beethoven’s example, this cuckoo can appear as a solitary sound, not as part of an entire sound world about nature. One of the early names for this movement was ‘Frühling und kein Ende’ (Spring without End).

The second movement, Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell, seems much like Haydn’s playful dance movements that make fun of the sturdy peasant dancing in wooden clogs. Mahler took the traditional third-movement minuet and trio section and moved it to second place. He took the country and village dances he saw in growing up and adds a yodel-like melody from the folk songs of Austria. It’s almost like a snapshot of a lost youth. The middle section pulls us to the city with a waltz-like feel before the return of the thumping country dance.

II. Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell

Osmo Vänskä

The third movement is not just a slow movement, it’s a monumentally slow movement. Mahler’s inspiration was a children’s picture by Moritz von Schwind entitled The Huntsman’s Funeral. The world is upside-down – the hunted become the pallbearers, and the hunter is the dead victim. The cortege is led by animal musicians and weeping foxes follow the byre. The mood of the music seems to capture the ambivalence of the imagery – and the use of a children’s song rhyme (Bruder Martin, or Frère Jacques) underscores the irony.

III. Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen

The final movement opens with pure drama and emotion – timpani strikes in the percussion and dramatic poses in the winds and strings. This movement comes without a break after the slow movement and funereal atmosphere is broken immediately. It’s a Gothic break: sweeping lines in the strings, abrupt chords in the brass, little music cells repeated over and over, and military-like themes that anything but heroic. Finally, he develops a rich theme that subsumes all his heartbreak. Themes from the first movement make their appearance, the keys shift and suddenly, the un-heroic melodies of the beginning are recast in a new light. The final movement, while encapsulating the complexities of the earlier movements, becomes a comment on them.

IV. Stürmisch bewegt

In his first symphony, Mahler looks to the past and comes up with a new solution to the primary problem facing composers after Beethoven – how to use the past but make a new statement at the same time.

In this performance, Osmo Vänskä and the Minnesota Orchestra give a performance that often brings you deeper into Mahler’s world. The clarity of their playing, particularly in the second movement, lets you hear details that may have previously escaped your ears.