You’ll recognise it instantly: that happy “lift” at the end of a piece in a minor key, an unexpected lightening of the mood, like a ray of sunshine peeping through the rain clouds. That expressive “lift”, an expression of happiness or contentment, is a Picardy Third.

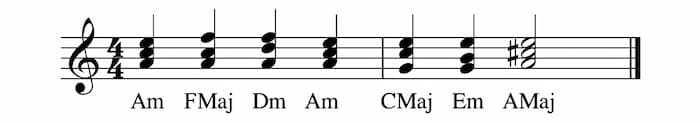

A Picardy Third, Picardy Cadence, or Tierce de Picardie in French, is a major chord at the end of a piece or section of music in the minor key. It is achieved by raising the third of the expected minor triad by a semitone. For example, in a piece in A minor, instead of ending on the minor triad chord of A C natural E, introducing a Picardy Third would raise the C natural by a semitone to C sharp, and turn the chord into an A major triad.

The Picardy Third originated in Western music in the Renaissance and by the seventeenth century, it was common in both religious and secular music. There are many examples in the music of J.S. Bach, and his contemporaries, and many of Bach’s Chorales scored in a minor key end with a Picardy Third, creating powerful nuances in mood and expression in the music. The seriousness, pathos or profound message of the music prior to the cadence is thrown into greater relief by the change of mood suggested by the Picardy Third.

Although less common in music from the Classical era, the Picardy Third does still make an appearance; for example, at the end of the first movement of Beethoven’s final piano sonata, Op. 111, where the transition from the fierce darkness of C minor to the “happier” major key and the use of the Picardy Third in the closing cadence creates a calmness in preparation for the serenity in the opening of the second movement. This switch from minor to major is also used to great expressive effect by Schubert, creating emotional chiaroscuro or ambiguity, sometimes within the space of a single phrase or even just a few bars. Chopin also uses the Picardy Third, and switches from minor to major, most notably in his minor key Nocturnes.

Examples of the Picardy Third in piano music:

J.S. Bach: Prelude in C minor, BWV 847

After the relentless seriousness of what has gone before, the final C major triad at the end of this prelude brings a wonderful bloom of sound and an uplifting sense of hope.

J.S. Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, BWV 846-869 – Prelude No. 2 in C Minor, BWV 847 (George Lepauw, piano)

J.S. Bach: Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 659

The same effect is achieved at the end of Busoni’s transcription of Bach’s Chorale, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 659 – and here the Picardy Third is “announced” ahead of the final bar by the introduction of the raised third (B natural) in the bar before.

J.S. Bach: 18 Chorales, BWV 651-668, “Leipziger Choräle”: Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 659 (arr. F. Busoni for piano) (Igor Levit, piano)

Schubert: Piano Sonata in F minor, D 571

Schubert was a master of ambiguity in his use of major and minor modes, and his ability to switch between major and minor allows the music to move from uncertainty to warmth, from nostalgia to melancholy in the space of just a few chords or bars. This device is used most poignantly in the unfinished Sonata in F minor, D571. The sadness of the minor key is made even more intense by the switches to the major.

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 8 in F-Sharp Minor, D. 571 (Yehuda Inbar, piano)

Chopin: Nocturne No. 15 in F Minor

Chopin employs the Picardy Third in his minor key Nocturnes, and in some instances, the major key cadence is “prepared” several bars ahead, thus immediately transforming the mood of the music (for example, Op 27, No.1). The Nocturne Op. 55 No. 1 in F Minor, ends in F major, bringing a sense of peace and tranquillity to the music, further enhanced by the rolled pianissimo F major chords.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Frédéric Chopin: Nocturne No. 15 in F Minor, Op. 55, No. 1 (Maurizio Pollini, piano)