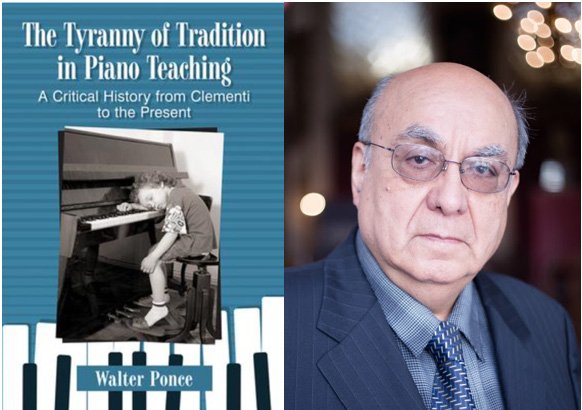

Walter Ponce and his latest book “The Tyranny of Tradition in Piano Teaching”

This is a sharp, humorous critique of book tradition of piano instruction and the current music education system, particularly in the United States. Author, Walter Ponce, is an internationally acclaimed pianist, pedagogue, and Professor Emeritus at the State University of New York and Distinguished Professor Emeritus at UCLA (where he was Director of Keyboard Studies). While the title of the book may seem exaggerated, Ponce illustrated some real tyrants of keyboard pedagogy and the dysfunction of the teacher-student relationship. It has given me a fresh perspective from which to consider my own journey of studying, performing and teaching of the last 30 years.

What Tyranny?!

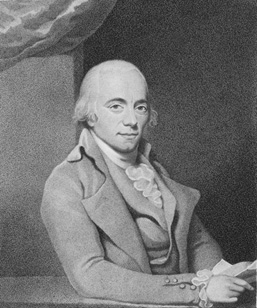

Muzio Clementi

Ponce’s ideology of teaching is to find the best suit for individual students. He encourages students to participate in masterclasses and take advantage of outside learning opportunities. He believes strongly in freedom in education valuing students’ opinions and he adapts such idea into his teaching. The tradition of tyranny began with Muzio Clementi and is characterized by excessive technical exercises and abusive, didactic teaching style. Known as “the Father of Piano,” Clementi was a piano manufacturer, composer, performer, teacher, publisher, and true representative of the Enlightenment Period. His influence was significant in the piano world of the 19th century. Many composers used his keyboard sonatas as models of compositions. Beethoven ranked Clementi’s compositions highly, playing them and using them for teaching. Clementi published a pioneering piano method book, and Ponce has a strong opinion about it.

1.Method Books and Drilling Exercises

Clementi’s method book Gradus ad Parnassum © Peters Edition Ltd

In the book, Ponce relentlessly questions the reasons of using method books and drilling exercises. Clementi’s method book, Gradus ad Parnassum, also known as The Art of Playing the Piano, written in 1817, became the model for instruction books that would follow, including those written by Carl Czerny, Cramer, and Charles-Louis Hanon, which we continue to use today. According to Ponce, Clementi’s legacy is the establishment of the “mentality that valued technical considerations over musical substance.” In Gradus ad Parnassum, the one hundred studies provide comprehensive drills for pianists to explore different figurations and patterns, as well as compositions which focus on contrapuntal and chordal playings. The approach of Gradus ad Parnassum, is the “backbone of all post-C.P.E. Bach methods.” Ponce argues, the finger-only practice, addressed in the studies, is not only a waste of time but also causes painful physical problems. The traditional long hours of practicing drills and exercises, promoted by Clementi, even result in “disruptions of the mental connection.” Ponce refers to this “excessive (practice) time with monotonous and uninteresting exercises” is a negative transfer of learning- it enables students to reach the precision but it “inevitably leads a player to lose sight of the musical goals of a piece.” Instead, he believes a good musical mind helps facilitate a good technique.

2. Authoritarian Image of Teachers

“Abusive behavior, absolute obedience, and large-scale indoctrination became the norm in piano teaching of the nineteenth century-regrettably still practiced today in some parts of the world.”

Clementi was a famous piano teacher during his time. He and his followers, including Czerny, established a traditional instruction method in which the teachers assume absolute authority over their pupils. In chapter six of the book subtitled The Legacy and Religion, Ponce illustrates this authority thusly, “the foundation for its durability can be found on these biblical tenants: I will surrender my life to the Lord…..We need only substitute ‘my teacher’ for ‘the Lord’.” (I laughed out loud when I was reading it.) Traditional piano teaching, according to Ponce, is based on humiliation and abuse. Ponce regards the period between 1850 and 1950 as the “Age of Meanness”. Piano teachers, ranging from local to famous teachers, all expressed total authority over students. As a result, students suffered from a suppression of cognitive thinking and they were forced to constantly adapt to their teachers’ demands under numerous fears, insults, and threats. To illustrate the far reach of tyranny, Ponce uses examples of Arthur Rubinstein, Sergi Rachmaninoff and Claudio Arrau and their days as piano students who were afraid of and controlled by their teachers. He provides anecdotes to show Clementi’s negative influence on other teachers, including Friedrick Wieck, Adele Marcus and Theodore Leschetizky. Ponce even describes his own unpleasant experiences working with celebrated teachers as a student. Such abusive teaching became a concern and has largely improved since 1970 but Ponce claims such teaching still exists.

Qualities of Good Teachers

What are the qualities of a piano teacher? Ponce praises the teaching approaches of Franz Liszt, Artur Schnabel and Heinrich Neuhaus who emphasizes the expressions of music rather than excessive practice of technical studies. Ponce has listed 10 indicators for us to identify a good teacher. For instance, he suggests a good teacher has to be able to perform. A good teacher also emphasizes the importance of sight-reading skills instead of solely focusing on finger skills. Students and parents should be cautious to choose teachers who constantly gives themselves the credit and boast about the fast progress of their students. Ponce believes skills take patience and time to grow. Playing music should also come from our expressive inner self students have the rights to learn what they truly love. Therefore, teachers should always be flexible and open-minded of finding the right genres and repertoire for their students. As a piano student and a piano teacher, I hope this book may lead to a more optimistic teaching environment for both teachers and students.

Born in Hong Kong, Fanny is currently pursuing a doctorate degree of Piano performance and pedagogy at the University of Kansas under the instruction of Dr. Scott McBride Smith. She received her master degrees in Piano Performance and Musicology from the University of Missouri- Kansas City (UMKC). Fanny lives in Kansas City where she maintains a busy performance and teaching schedule. As a musicologist, she has presented her papers at the conferences of the College Music Society (2019), Britain and the World (2019), and the Midwest Music Research Collective (2018).

Born in Hong Kong, Fanny is currently pursuing a doctorate degree of Piano performance and pedagogy at the University of Kansas under the instruction of Dr. Scott McBride Smith. She received her master degrees in Piano Performance and Musicology from the University of Missouri- Kansas City (UMKC). Fanny lives in Kansas City where she maintains a busy performance and teaching schedule. As a musicologist, she has presented her papers at the conferences of the College Music Society (2019), Britain and the World (2019), and the Midwest Music Research Collective (2018).

And, I suppose that Ponce has produced pianists on the level of those who came from the studios of Leschetizky and Adele Marcus? The proof of the teaching is in the success of the pupils produced…what rubbish!

wow

I wholeheartedly agree with Walter Ponce. This authoritarian tradition of teaching just doesn’t work and the students who succeed do so despite their abusive training. Anyone who sets their mind to it can go very far with the piano as long as they start at the bottom and work up from there. I think it’s very necessary to play as many easier to play pieces as possible in order to acquire a certain naturalness of playing which can only be learned with experience. Play them with taste and practice them thoroughly until every passage dances and feels under control. Learn all the easier Haydn sonatas before tackling one of difficulty. It’s not desirable to memorize them all but you should be able to play them from the score. Learn all the Bach inventions and sinfonias. Start with Beethoven’s op. 79 or even both op. 49 instead of op. 13. If you spent time playing Bach (WTC, English suites, Partitas etc.) and you played all the easier Beethoven sonatas first, you can learn all 32! Why struggle playing a Chopin etude or Rachmaninoff when you could be playing all 153 pieces in Bartok’s Mikrokosmos? Enjoy the low lying fruit. Music is meant to be enjoyed and you should always have the feeling of making progress. Hard work and sacrifice are certainly part of it but too much struggle is counter productive. Build your skills from the bottom up and enjoy the journey.

Well said, Jason! Couldn’t agree more about the importance of “low-lying fruit,” allowing students to learn more repertoire that is well within their reach rather than pushing their technical and musical boundaries with fewer and more difficult pieces.

It is evident that Mr. Ponce had a trauma in his learning due to inadequate teachers or methodologies. But his hatred of Clementi is in no way justified. First of all, you have to situate Clementi in his context. If he had such spectacular success as a piano teacher and trainer of future pianists, it was not because of a supposed “tyranny”, but because of his ability to teach with methods appropriate to his time and to the characteristics of his students. Second, the use of the methodologies by subsequent teachers in the teaching profession is solely their responsibility. Clementi did not force anyone to follow his method, let alone create a caricature of himself, which, deep down, is what teachers lacking sense, imagination or their own pedagogical creativity have done. Thirdly, one only has to listen and analyze his music without the usual prejudices to realize that it is not at all cold and expressionless music. You just have to interpret it well, as is normally done with any other author. There are pianists who do not know or do not want to overcome the technical barrier and when they play Clementi they put on their mechanic’s hat instead of expressing the music as they would with Mozart or Beethoven. Anyone is responsable from his acts.