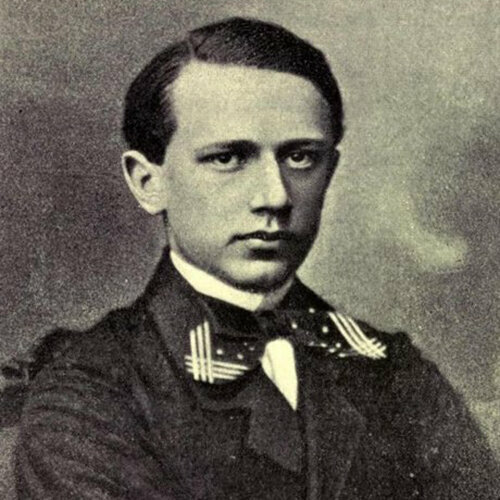

Yosif Kotek with Tchaikovsky

Yosif Kotek with Tchaikovsky

The interaction between teacher and student, at its most fundamental level, might be described as the attempt to forge a meaningful relationship to the past. This relationship depends on the extent to which it takes traditions more or less tacitly for granted, and on the ways it receives the legacy of still earlier ages. As such, the teacher-student relationship is invariably defined by the teacher’s ability to formulate and communicate these traditions. Given the idealized and somewhat erudite nature of this statement, one has to wonders why Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) accepted Nikolai Rubinstein’s invitation to teach harmony at the Moscow Conservatory in 1864. Although he enjoyed a steady salary and was inducted into the artistic and higher social circles of Moscow society, he always found teaching a rather boring chore and emotional strain. What did excite him undoubtedly, however, was the steady stream of impressionable young man, who in the extended tradition of Russian serfdom were expected to submit to the wishes of their superiors in every respect. It is therefore hardly surprising that Tchaikovsky engaged in numerous sexploitations, even driving one of his young charges into committing suicide. The general acceptance of this sexual hierarchy was so deeply ingrained that 14 years after this tragic student suicide, Tchaikovsky could simply comment in his diary, “it seems to me that I have never loved anyone so strongly as him”.

Tchaikovsky: Valse-Scherzo, Op. 34

In 1870, a debonair and dashing violin student entered the Moscow Conservatory. Yosif Kotek was as talented as he was promiscuous, and Tchaikovsky promptly fell “a little bit in love with him”. After six years of teasing and bantering, which undoubtedly also included an occasional lesson in invertible counterpoint, Tchaikovsky finally declared “it is not possible to restrain oneself from one’s weaknesses”. In a letter to his brother Modest, Tchaikovsky revealed the most intimate details of the burgeoning relationship: “I am incapable of expressing to you the full degree of bliss that I experienced by fully giving myself away… When he caresses me with his hand, when he lays with his head inclined on my breast, and I run my hand through his hair and secretly kiss it… passion rages within me!… I wrapped him up, hugged him, guarded him…After dinner he felt sleepy…and he tenderly ridiculed my expressions of affection and kept repeating that my love is not the same as that of [his boyfriend] Porubinovskii. Mine is supposedly selfish and impure…” As an immediate musical consequence of their encounter, Tchaikovsky gave birth to the Valse-Scherzo for violin and orchestra, Op. 34. He not only dedicated the composition to Kotek, but also allowed his “student” to furnish the orchestration. Yet, things quickly cooled as Kotek—who alongside Claude Debussy, Nikolai Rubinstein and Henryk Wienawski was also financially supported by Nadezhda von Meck—engaged in countless amorous episodes with women in von Meck’s estate. Once his patron realized the extent of Kotek’s philandering, she quickly withdrew all financial support, and Kotek mistakenly blamed Tchaikovsky for having revealed their secret. Teacher and student unceremoniously parted ways, with Tchaikovsky attempting to publicly disguise his true sexual orientation at the bosom of heterosexual marriage, and Kotek moving to Berlin to study with Joseph Joachim. Little did they know that their passion would be rekindled in very short order, and that another exciting musical offspring would see the light of day. I’ll tell you more about that in Tchaikovsky-Kotek 2.