J.S. Bach (1685–1750) came to Cöthen in 1717 as Kapellmeister and Chamber Music Director to Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen and remained there until he left for Leipzig in 1723. In those seven years, he could explore instrumental music because the court did not require him to write church music. When he got to Leipzig, he began his work in cantatas for the church year, but in Cöthen he could concentrate on music for harpsichord and clavichord, which would be used for teaching both his family and outside pupils.

Elias Gottlob Haussmann: Johann Sebastian Bach, 1746

The 18th-century music theorist Johann Mattheson developed the idea of the stylus phantasticus as a musical style that was both theatrical and improvisatory. He praised Handel’s opera accompaniments as a particularly fine example of this and gives this description of the style:

For this style is the most free and unrestrained manner of composing, singing and playing that one can imagine, for one hits first upon this idea and then upon that one, since one is bound neither to words nor to melody, only to harmony, so that the singer or player can display his skill. All kinds of otherwise unusual progressions, hidden ornaments, ingenious turns and embellishments are brought forth without actual observation of the measure and the key, regardless of what is placed on the page, without a formal theme and ostinato, without theme and subject that are worked out; now swift, now hesitating, now in one voice, now in many voices, now for a while behind the beat, without measure of sound, but not without the intent to please, to overtake and to astonish. These are the essential marks of the fantastic style.

This paragraph, from Chapter 10 of Mattheson’s Der volkommene Capellmeister (The Perfect Kapellmeister) (1739), describes exactly what we will be hearing in Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue. Written in Cöthen and later revised in Leipzig in 1730, the work is unique in Bach’s output. One of the notable elements of both the Fantasia and the Fugue is their exploration of remote keys, which would become more common in Bach’s organ works. We can see parallels in this work with another fantasy piece from the same time: Brandenburg Concerto No. 5’s great harpsichord cadence that takes up the entire second movement. The two works were both written in Cöthen.

Leopold von Anhalt-Köthen

Bach’s extraordinary exploration of the free fantasia, which would be later thoroughly explored by his son C.P.E. Bach, is thought to be a tombeau for his wife Maria Barbara, who died suddenly in 1720 while Bach was away with Prince Leopold on a visit to Karlsbad. Bach married again in 1721 to Anna Magdalena Wilcke.

That the work was important to Bach is evidenced by the fact that, although it is clearly an improvisatory work, it was carefully annotated and preserved in several copies in the Bach household.

Although the work is carefully annotated, Bach still forces the performer to use her imagination. One writer noted:

In two ways, Bach guarantees that the performer dares to be improvisatory when she plays this piece. First, from measures 28 to 48 the score gives carefully written-out figuration alternating with large half-note chords marked “arpeggio”, forcing the performer to make choices about how to realise this “short-hand” notation. Then in measure 49 a plaintive melody marked Recitativ begins to alternate with abrupt almost violent short chordal passages, calling the performer to imagine how she can imitate the new character that has suddenly come on stage: a solo voice singing a lamento, accompanied by continuo.

The clavier in Bach’s time was an instrument of the home to be used for practice and pleasure. It was the instrument for small, quiet gestures; big gestures were reserved for the organ.

The Fantasia is a liberated work, divorced from the usual rules of tonality, as signalled by its ‘Chromatic’ title. Long scalar runs are interrupted by quiet, reflective cascading passages, creating something truly fantastique. The Fugue uses motives from the Fantasia to drive its swift movement. The opening subject is extended, then is answered in the alto and closes with a grand entry of the subject over a pedal.

J.S. Bach: Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue in D minor, BWV 903

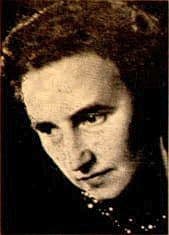

Helma Elsner, 1960

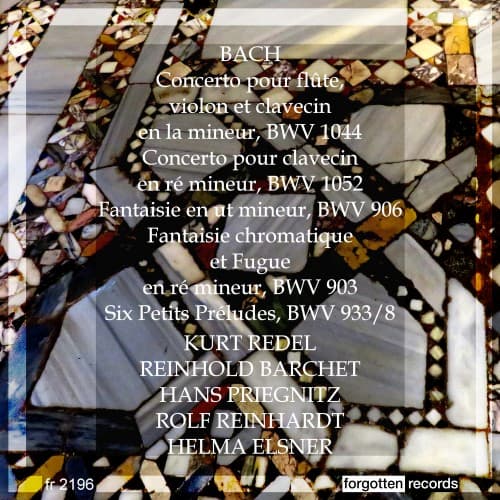

This recording was made in Stuttgart in 1958 with Helma Elsner on clavier. Elsner (1927–2000) was a renowned German harpsichordist who, after studying with private teachers, attended the conservatoires in Essen and then Berlin. After teaching in Essen at the Folkwang School, she started her concert career, traveling around Europe. Her recordings in the 1950s and 1960s include the solo keyboard works and harpsichord concertos by J.S. Bach, fantasias for harpsichord by Georg Philipp Telemann, concertos for harpsichord by Joseph Haydn, and keyboard music by J.S. Bach’s sons. She also participated in recordings of cantatas by J.S. Bach and George Frideric Handel.

Performed by

Helma Elsner

Recorded in 1958

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter