The Italian composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895–1968) developed a private system of musical cryptography and used it to create a cycle of compositions. His Greeting Cards, op. 170, cycle began in 1963 and ended with the composer’s death.

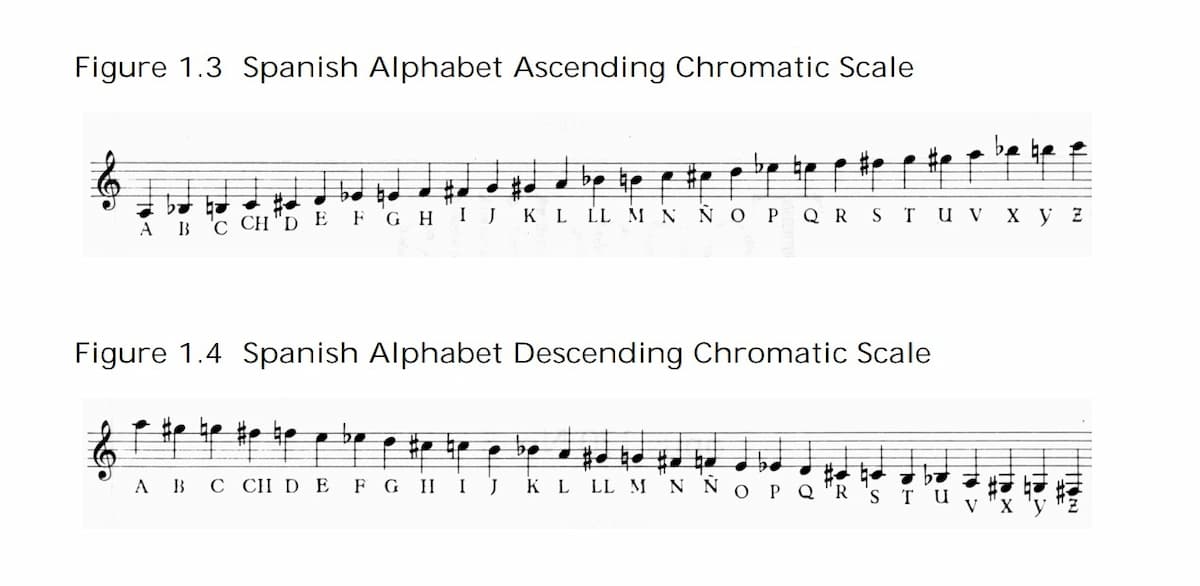

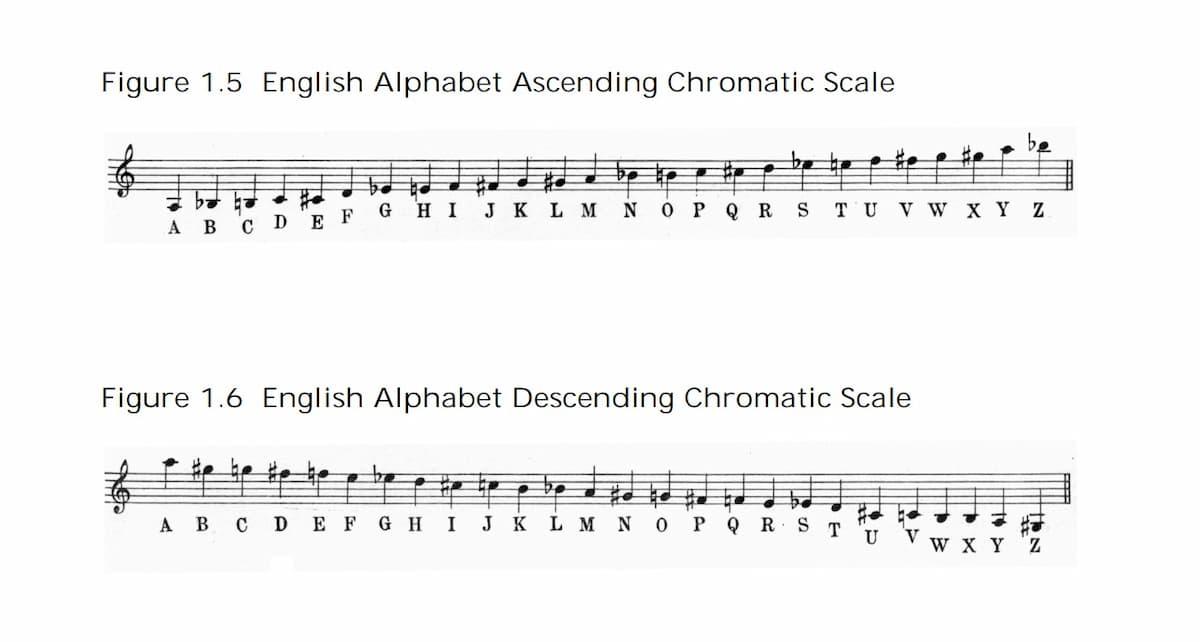

His system of writing was based on ‘two thematic groups based on two chromatic scales, one ascending and the other descending, in which each note is paired with a letter of the alphabet. The first and last names of the person to whom the piece is dedicated are used to develop the thematic sequence’.

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco

Musical cryptography, or a musical motif that hides a sequence of letters can be traced back to the early 16th century. Josquin des Prez wrote his Missa Hercules Dux Ferrariae using the solmization syllables inherent into vowels of ‘Hercules Dux Ferrariae’ to create his musical motif:

Her – re

cu – ut

les – re

Dux – ut

Fer – re

ra – fa

ri – mi

ae – re

resulting in re ut re ut re fa mi re: D-C-D-C-D-F-E-D.

Other systems for translating names into music were also used, such as J.S. Bach’s use of his name in music as Bb – A – C – B, using the German form of the solmization syllables.

In Castelnuovo-Tedesco made 4 different alphabets: English, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish to take into account the unique letters of each alphabet, for example, Italian has no letter ‘J’, the Spanish alphabet has to include CH, LL, and Ñ, and leave out ‘W’, and so on.

By basing his musical cryptography on a chromatic scale, Castelnuovo-Tedesco was writing in a twelve-tone system, and in the foreword to Op 170/6, the recipient, Sigfried Behrend, noted ‘The composer used all the “little tricks” of the twelve-tone system (inversions, retrogressions etc.) and tried to give a “psychological portrait” of the different artists’.

Andrès Segovia

Having first created his system because he wanted to write a work for his teacher, Ildebrando Pizzetti, and needed to find a way to make the two ‘Z’s into music. His next work was done using the full name of the organist E. Power-Biggs: Edward Power-Biggs and after that the Op. 170 was born. He wrote a Tango for André Previn (piano), a Valse for Piatigorsky (cello and piano), a Tonadilla for Andrès Segovia (guitar), and so on. By the time of his death, he had written 51 different little works (he considered them merely ‘exercises’ or ‘alphabetical pieces’). One recipient said that Castelnuovo-Tedesco had told him that his aim in writing the works was to make ‘a person happy for one day’.

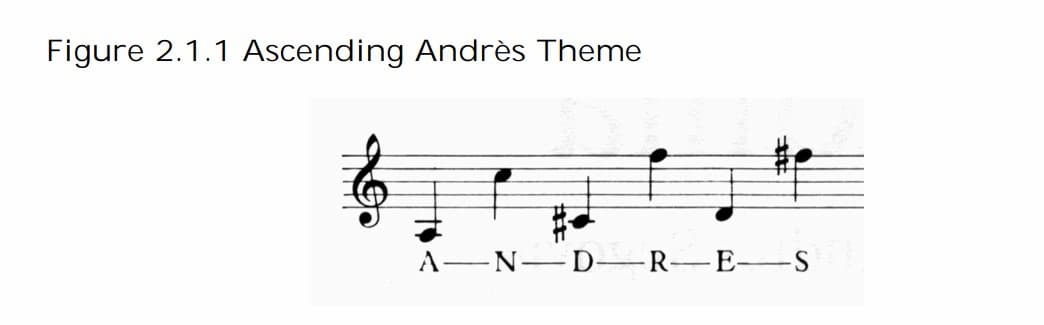

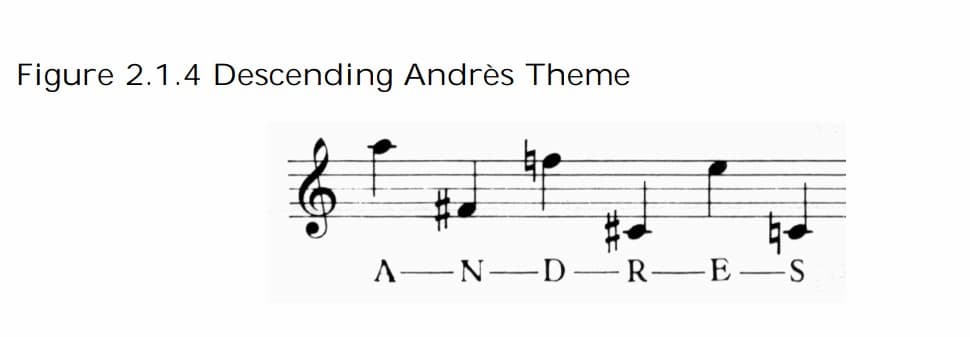

Twenty-one of the 51 works are for guitar, the first being Tonadilla sur le name de Andrès Segovia, Op. 170/5. The work uses the Spanish alphabet scale.

Spanish Alphabet scale (from Asbury: 20th century Neo-Romantic Serialism, 2005, University of Texas at Austin, dissertation)

From the scale, both ascending and descending themes are created, using the dedicatee’s first and last name. Here are the two versions of the Andrès theme:

Ascending Andrès theme (from Asbury: 20th century Neo-Romantic Serialism, 2005, University of Texas at Austin, dissertation)

Descending Andrès theme (from Asbury: 20th century Neo-Romantic Serialism, 2005, University of Texas at Austin, dissertation)

In addition, Castelnuovo-Tedesco added quotations from the Concerto in Re piece that had brought the composer and performer together.

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco: Greeting Cards – Tonadilla on the Name of Andrés Segovia, Op. 170, No. 5 (Andrea De Vitis, guitar)

The Tanka written for the Japanese guitarist Isao Takahashi used the English alphabet scale. An ophthalmologist by trade, Takahashi was one of the leading Japanese guitar teachers and published a monthly guitar journal. Through his medical connections, he knew the Swiss physician Dr Albert Schweitzer, and through his musical connection, contacted Castelnuovo-Tedesco to write a work for the missionary doctor and organist. Castelnuovo-Tedesco, after first having trouble getting Schweitzer’s name into music, responded with a Chorale-Prelude on the name of Albert Schweitzer, Op. 170/18a and a Fugue, Op. 170/18b. For Takahashi, Castelnuovo-Tedesco created a Tanka, based on an ancient Japanese poetic form. The atmosphere is one of tranquillity and meditation.

English Alphabet scale (from Asbury: 20th century Neo-Romantic Serialism, 2005, University of Texas at Austin, dissertation

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco: Greeting Cards – Tanka (Japanese Song) on the Name of Isao Takahashi, Op. 170, No. 10 (Andrea De Vitis, guitar)

Castelnuovo-Tedesco was a serial tonal composer (as contrast with the more common serial atonal composers) who used the serial system in a tonal context. His skill as a writer of lyrical melodies comes to the fore in these little works.

None of the details of the composition shown here are intended to be heard, and, in fact, the audience should be completely unaware of them. They were a game the composer played with himself to create rules for composition, but always with the goal that satisfactory music would be the end result.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter