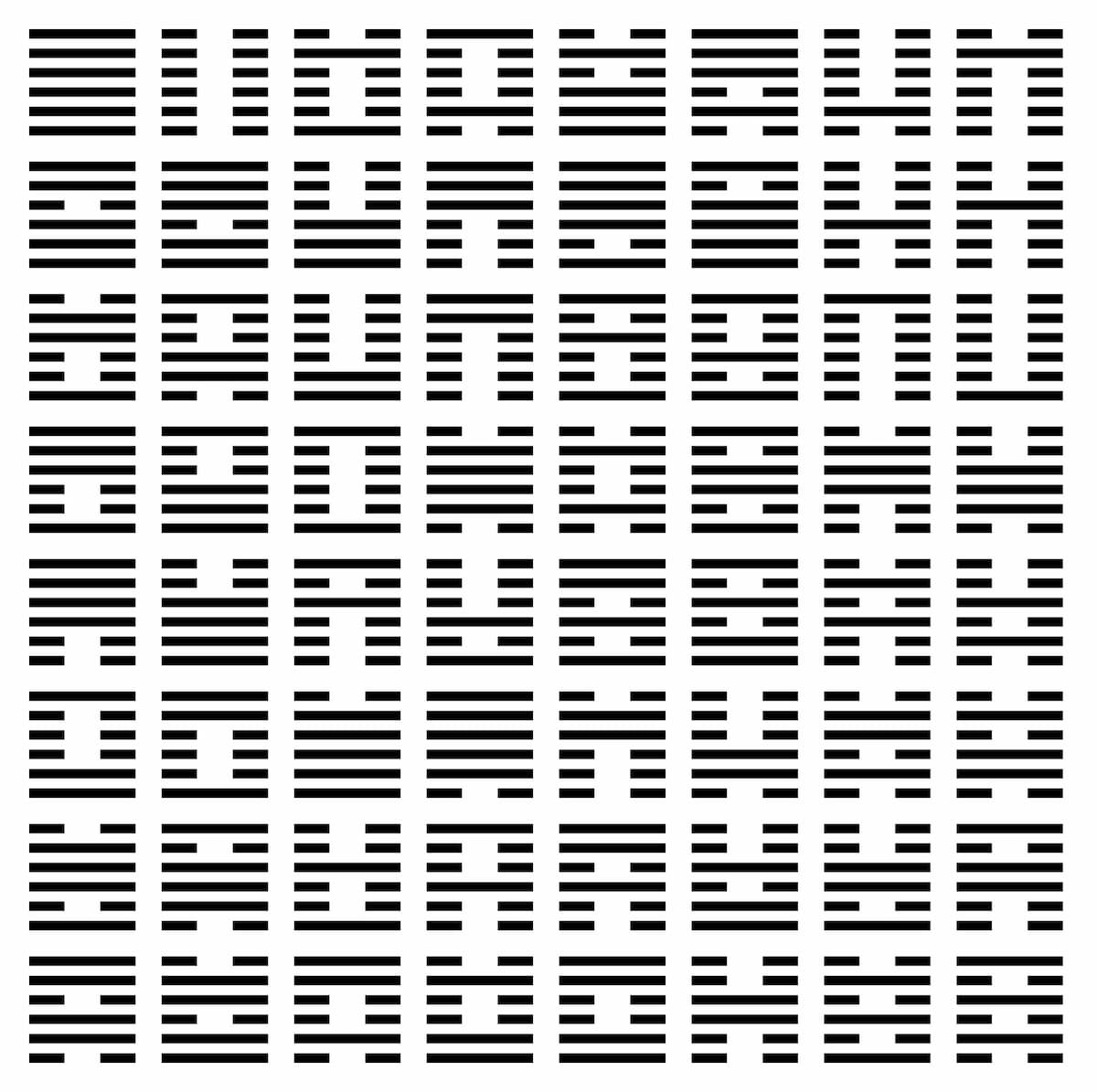

John Cage was given a book of the I Ching (Book of Changes), a classic Chinese text that uses a hexagram symbol, to create order out of seemingly random occurrences.

The I Ching hexagrams

One of the first works that he used the I Ching for was Imaginary Landscape No. 4 (March No. 2) in 1951. This work, for 24 performers at 12 radios, where one player controls the radio-station dial and the other controls the volume.

Imaginary Landscape No. 4 performance, 2013, Bilkent University

‘Cage employed the I Ching to create charts, which were used to refer to superimpositions, tempi, durations, sounds, and dynamics. In these sound charts, 32 out of 64 fields are silences. In the charts for dynamics, only 16 produce changes, while the others maintain the previous situation. Similar charts were produced and employed for the other parameters.’

John Cage: Imaginary Landscape No. 4 (March No. 2) (Ensemble Prometeo: Marco Angius, cond.)

Clearly, every performance of this work will be different, not based on his directions but on what comes through on the radio. These are works that are generated by using the I Ching, but each performance will be very different.

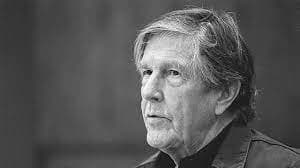

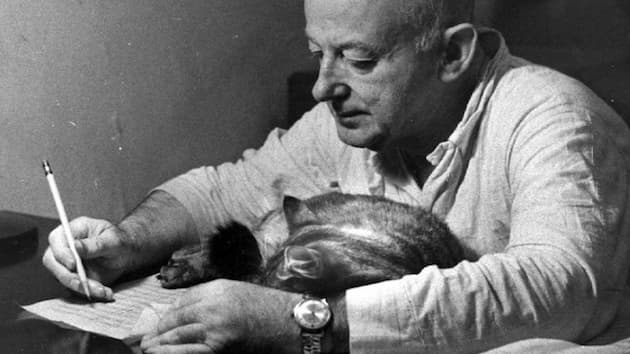

John Cage

His second work was Music of Changes, completed later in 1951. It is written in 4 books, completed between May and December 1951, and was written at the same time as his Imaginary Landscape No. 4. Whereas in Imaginary Landscape No. 4, Cage sought to use the random sounds that came from the radio to create a truly random piece, in Music of Changes, Cage created a chart to use the 64 hexagrams of the I Ching. To compose a short section of music, ‘The I Ching is first consulted about which sound event to choose from a sounds chart, then a similar procedure is applied to durations and dynamics charts.’ Other operations governed the addition of density, or layers, of sound.

The notation of the score is proportional: the horizontal distance between notes has been standardized, so that a quarter note is equal to 2. 5 cm (almost 1 inch). The stem of the note, not the note head indicates when the sound begins. Some notes are played on the keyboard, while others, going back to Cage’s earlier work with prepared pianos, involve the pianist striking different parts of the piano with special beaters, hitting the strings instead of the keys, or snapping the lid for a percussion effect.

John Cage: Music of Changes – IV. — (David Tudor, piano)

Both Imaginary Landscape No. 4 and Music of Changes are examples of indeterminacy, a compositional approach where some aspects of a musical work are determined by chance operations (the I Ching in these examples) or free choice on the interpreter’s part (as in Imaginary Landscape No. 4). Cage was not the inventor. We have to look back to the innovative compositions of Charles Ives earlier in the 20th century for that. His student, Henry Cowell, extended this to his own compositions, such as his Mosaic Quartet, where performers arrange the fragments of music in the score into different possible orders for performance.

Henry Cowell: String Quartet No. 3, “Mosaic Quartet” – I. — (Colorado String Quartet)

Henry Cowell: String Quartet No. 3, “Mosaic Quartet” – I. — (Colorado String Quartet)

Cowell passed the ideas for indeterminacy down to his friend and student John Cage and it was Cage who really became the pioneer of indeterminacy, often encouraged in his thinking by Cowell. Indeterminacy also had a great effect on the music of the 1950s and 60s – moving from Cowell’s and Cage’s ideas in the US to Europe, particularly following lectures Cage did in German at Darmstadt, Germany.

Henry Cowell

Some works were interesting experiments in music: dots printed on clear mylar sheets that could be placed over different kinds of lined music paper and then played. Music printed on unbound pages that could be then arranged in any order and performed by one to 25 pianists – the pages could be played right side up or upside down (Earle Brown, Twenty-Five Pages). Short music fragments can be played as many times as each member of an ensemble wants before moving on to the next fragment (Terry Riley, In C). All of these experiments with the concepts of writing music, performing music, or even how much music to play at all were important expansions of what was feeling like restrictive rules from the past. They weren’t always successful or even long-lasting, but composers were able to use them to create the new music of the 20th century and springboard new ideas for composition.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter