The story of Apollo and Daphne is upsetting to the modern psyche. She is pursued and to escape her pursuer, would rather become non-human than acquiesce. Or, you can view it from a different angle: despite being the ideal god, women just don’t want you. Or there’s the third-party problem and the role of Cupid and his arrow of gold and arrow of lead.

The story starts with Daphne, a nymph, daughter of the river god Peneus. She’s out in the countryside one day and comes to the attention of Apollo. Apollo, son of Zeus and Leto and brother of Artemis, was one of the most important of the Olympian gods. He had been teasing Cupid, saying that he was not a good archer and that Apollo was better. Cupid shoots Apollo with his golden arrow of love and then shoots Daphne with his lead arrow to make her despise Apollo and the chase is on. Daphne is Apollo’s first love but she will have none of it. She runs from Apollo and in desperation, calls to her father, the river god Peneus to help by destroying her shape. He transforms her mid-stride into a laurel tree. Apollo falls in love with that, too. He embraces the tree and kisses it and still she recoils from him. Apollo declares that if she won’t be his bride, then she/it will be his tree: laurel wood will be used to form his lyre and to make triumphal music, her leaves will become the circlet he wears. In her tree form she nods and agrees.

Any story like this with action, love, hate, and transformation was immediately taken up in art, poetry and music.

Piero del Pollaiuolo: Apollo and Daphne, ca 1470-80 (London: National Gallery)

Veronese: Apollo and Daphne, 1560-65 (San Diego Museum of Art)

Domenichino and assistants: Apollo pursuing Daphne, 1616-18 (London: National Gallery)

Theodor van Thulden: Apollo and Daphne, 1636-1638, (Madrid, Museo del Prado)

All of these are about the excitement of the chase – or the disappointing aftermath when she really escapes.

One painting asks the viewer to supply the action. J.W.M. Turner’s 1837 work, The Story of Apollo and Daphne, doesn’t place them seemingly even within view.

Turner: The Story of Apollo and Daphne, 1837 (London: Tate)

In the music world, the story was the basis for a number of operas and a few smaller works. The first acknowledged opera, although little of the music is extant, was Peri’s Dafne, written for performance during the Carnival of 1598 to be followed in 1600 by his next opera Euridice.

In 1608, Marco da Gagliano wrote his La Dafne, and it was performed in the Ducal Palace in Mantua. It had been written for the wedding celebrations of Prince Francesco Gonzaga of Mantua and Margherita of Savoy, but delays in the ceremonies delayed the production of the opera and it was performed some weeks after the actual ceremony. The libretto, written by Ottaviano Rinuccini, changes the story slightly, by having Dafne call out to her mother, not her father.

After Dafne’s transformation, the other nymphs mourn that they will not see her again: ‘Weep, O Nymphs, and Love weeps with you…

Marco Da Gagliano: La Dafne – Scene 5: Piangete, Ninfe (Fuoco e Cenere; Jay Bernfeld, cond.)

Francesco Cavalli (1602-1676) wrote his version of the story for performance at the Teatro S. Cassino in Venice. Using the same librettist, Giovanni Francesco Busenello, who had written Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea, Cavalli filled his opera with Gods, demi-gods and a lot of creative music writing. Since even by 1640 the norms of opera writing had not yet been codified, Cavalli’s work is quite different than we might expect.

In a great aria, Peneus appears and tells her that, although he can do nothing against Apollo since the Sun can dry up his water, he can transform her into a tree, the Laurel, which leaves never fall. As Peneus leaves, he says his waters will be her mirror and, henceforth, his river will be one of lament.

Francesco Cavalli: Gli amori d’Apollo e di Dafne – Act III, Scene 2: Figlia indarno da me soccorso (Carlo Lepore, Peneo; Marianna Pizzolato, Dafne; Galicia Youth Symphony Orchestra; Alberto Zedda, cond)

Apollo, seeing her change, has his own lament. His bitter tears water the tree. Cupid asks whose weapon was truly the stronger?

Francesco Cavalli: Gli amori d’Apollo e di Dafne – Act III, Scene 3: Ohime, che miro? (Mario Zeffiri, Apollo; Soledad Cardoso, Amore; Galicia Youth Symphony Orchestra; Alberto Zedda, cond)

One of the most famous settings was written by Handel in 1710. His Apollo e Dafne or La terra è liberate is a ‘secular cantata’ or a vocal work of an extended length, usually with different sections. Handel’s production of secular cantatas was superseded by his later production of both sacred cantatas, written for the opera-less Lenten season, and full operas. Handel sets the story uniquely as a two-voice cantata, a dialogue between Apollo and Dafne.

At the end, in a recitative, he declares ‘I will adore you forever’ to which she responds ‘I will abhor you forever’ and then he declares he will pursue her because she cannot be more rapid than the sun.

George Frideric Handel: Apollo e Dafne, HWV 122 – Recitative: Sempre t’adorerò! (Apollo, Dafne) (Kathryn Lewek, Dafne; John Chest, Apollo; Il Pomo d’Oro; Francesco Corti, harpsichord and cond.)

And then a rapid chase…

George Frideric Handel: Apollo e Dafne, HWV 122 – Aria and Recitative: Mie piante correte (Apollo) (John Chest, Apollo; Il Pomo d’Oro; Francesco Corti, harpsichord and cond.)

…but Dafne is gone. He looks for her and then, once he discovers her new identity, declares that ‘You will not be harmed by winter’s ice, | Nor will lightning from heaven | Touch your sacred and glorious leaves.’

George Frideric Handel: Apollo e Dafne, HWV 122 – Recitative: Che vidi, che mirai? (Apollo) (John Chest, Apollo; Il Pomo d’Oro; Francesco Corti, harpsichord and cond.)

The work closes with his lament and vow to water her with his tears, and will use her branches to crown supreme heroes.

George Frideric Handel: Apollo e Dafne – Aria: Cara pianta, co’miei pianti (Apollo) (John Chest, Apollo; Il Pomo d’Oro; Francesco Corti, harpsichord and cond.)

By concentrating solely on the two protagonists, Handel has created a work that telescopes the whole story down, while magnifying its effect.

Other composers also took up the story, including Johann Joseph Fux, who wrote the chamber opera Dafne in lauro in 1714, and the German composer Graun (either Carl Heinrich or Johann Gottlieb) who wrote a 4- movement version of the Daphne story, Apollo amante di Dafne, as an Italian solo cantata that focuses solely on the end of Apollo’s ill-fated attempt on Daphne. Four lines into the first recitative, Dafne has already transformed.

Carl Heinrich Graun: Apollo amante di Daphne – Ferma, Dafne crudel! (Hanna Morrison, Apollo; Main Baroque Orchestra, Frankfurt)

One modern composer to take up the story is American composer Jonathan Dawe (b. 1965). His opera L’Dafne from 2006 is ‘an opera of 311 notes, exactly & a sinfonia & ritornello of 80 notes’ as the title says. In this 5-minute opera, Apollo first slays a dragon, makes fun of Cupid for shooting blind, sees Dafne, Cupid shoots, and Apollo and Dafne both lose.

Jonathan Dawe: L’Dafne: Balletto II – Dafne transforms into Foliage (Samuel Armstrong, alto trombone; Clara Lyon, violin; Serafim Smigelskiy, cello; Joseph Kelly, percussion; Jeffrey Milarsky, cond.)

Apollo describes Dafne ‘Hands stretched toward heaven, | Clothed with wild boughs | …green flowing sapling’ and then his reaction ‘I languish | I die.’ None of this watering her with his tears or keeping her leaves for the victors. He just dies. Metaphorically, I’m sure.

Jonathan Dawe: L’Dafne – Act III: Near the forest grove (Karim Sulayman, Apollo; Samuel Armstrong, alto trombone; Clara Lyon, violin; Serafim Smigelskiy, cello; Joseph Kelly, percussion; Jeffrey Milarsky, cond.)

Interest in mythological subjects, the focus of so many of the early operas, fell off as composers and librettists got better control of the form. Dramatic love stories, political intrigue, lost heirs, and magical actions supplanted stories of gods and goddesses.

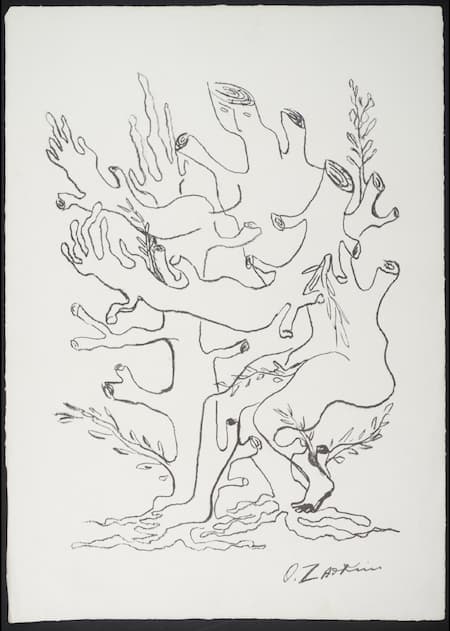

And finally, one more image of Daphne transforming, but one that eliminates any image of Apollo. She’s caught like most artists portray here – one leg still human, but the rest rapidly becoming a tree – her face remains at the top, but she seems to have grown a dozen arms.

Ossip Zadkine: Daphe – Treeform, 1964 (London: Tate)

Modern commentators see the story in the light of the me-too movement: power in pursuit of a helpless innocent who has her voice silenced in her effort to escape. Old stories are new again.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter