Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) had an interesting personality, to say the least. His vanity was notorious as he boasted of his fame and illustrious patrons. Apparently, he also told everybody who wanted to know or not, that he “could compose a concerto in all parts more quickly than it could be copied.” He inflated the number of his published works by counting each opus double, and he even claimed to have composed 94 operas.

Caricature of Antonio Vivaldi, 1723

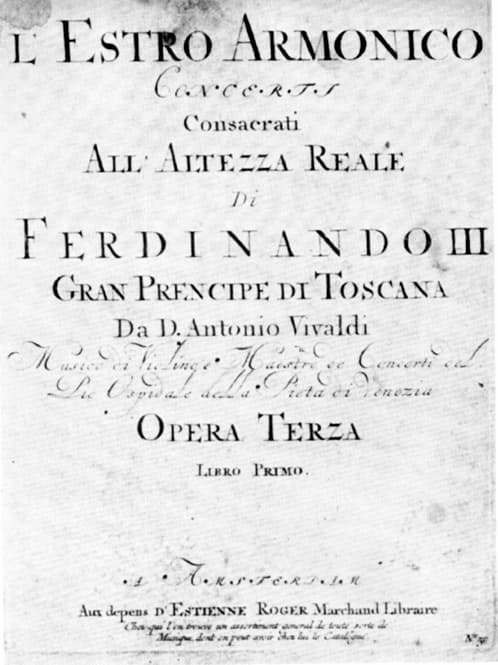

Alongside his vanity, Vivaldi was extremely sensitive to criticism as he writes in two of his dedications, “my efforts, which are perhaps spoken ill of by the critics,” and he was preoccupied with money. Working as a successful teacher at the orphanage called the “Pio Ospedale della Pietà “(Devout Hospital of Mercy) in Venice, Vivaldi was also seeking recognition as a composer. His first published works date from 1705, and he followed his initial set of 12 chamber sonatas with a second set in 1709. However, it was the publication of his Opus 3, “L’estro armonico” (the Harmonic Inspiration), in 1711 that made Vivaldi internationally famous.

Antonio Vivaldi: “L’estro armonico,” Op. 3, No. 5 (RV 519)

Undoubtedly, a number of the 12 concertos divided equally into works for one, two, and four solo violins had been known to some professional musicians on a local level, but they now spread like wildfire throughout the musical world. For a good many musicians, the Vivaldi Opus 3 was a revelation. A scholar writes, “the range and consistent quality of his invention, his many subtle original touches and expression were now available to all, and the influence of his art and the growth in his reputation were considerable. Here, suddenly it would appear, was a genius composer of a high order of original accomplishment, raising the concept of the instrumental concerto to an altogether higher plane than hitherto.” How do we best assess the immediate popularity of this work during the composer’s lifetime? For one, Op. 3, No. 5 (RV 519) was by far the most popular concerto of the set in the British Isles, and according to Michael Talbot, “the work was so often performed in public and private that it was simply referred to as “Vivaldi’s Fifth.” Secondly, the entire set was immediately subject to transcriptions, a process of creative rewriting that continues today.

Antonio Vivaldi: “L’estro armonico,” Op. 3, No. 1 (RV 519) (Arranged for Organ) (James Orford, organ)

Antonio Vivaldi’s “L’estro armonico”

Vivaldi was a clever businessman, as he had selected the Amsterdam publisher Etienne Roger over local Italian printers. Venetian printing houses at the time used antiquated technology, as they needed a separate block for each note. “The appearance was often shambolic, particularly where large groups of semiquavers were concerned.” Roger, on the other hand, printed music using copperplate engravings, which produced aesthetically pleasing, easy-to-read results. In fact, Vivaldi acknowledged Roger’s superior technology in the preface to “L’estro armonico.” In addition, Roger had a large distribution network, particularly in Northern Europe, “where at various times he had agents in Berlin, Brussels, Cologne, Halle, Hamburg, Leipzig, Liège, London and Rotterdam. Roger’s state-of-the-art technology combined with Vivaldi’s cutting-edge concerto style proved to be an immediate success.” It was just a question of time before these attractive prints made it into the hands of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Antonio Vivaldi: “L’estro armonico,” Op. 3, No. 8 (RV 522)

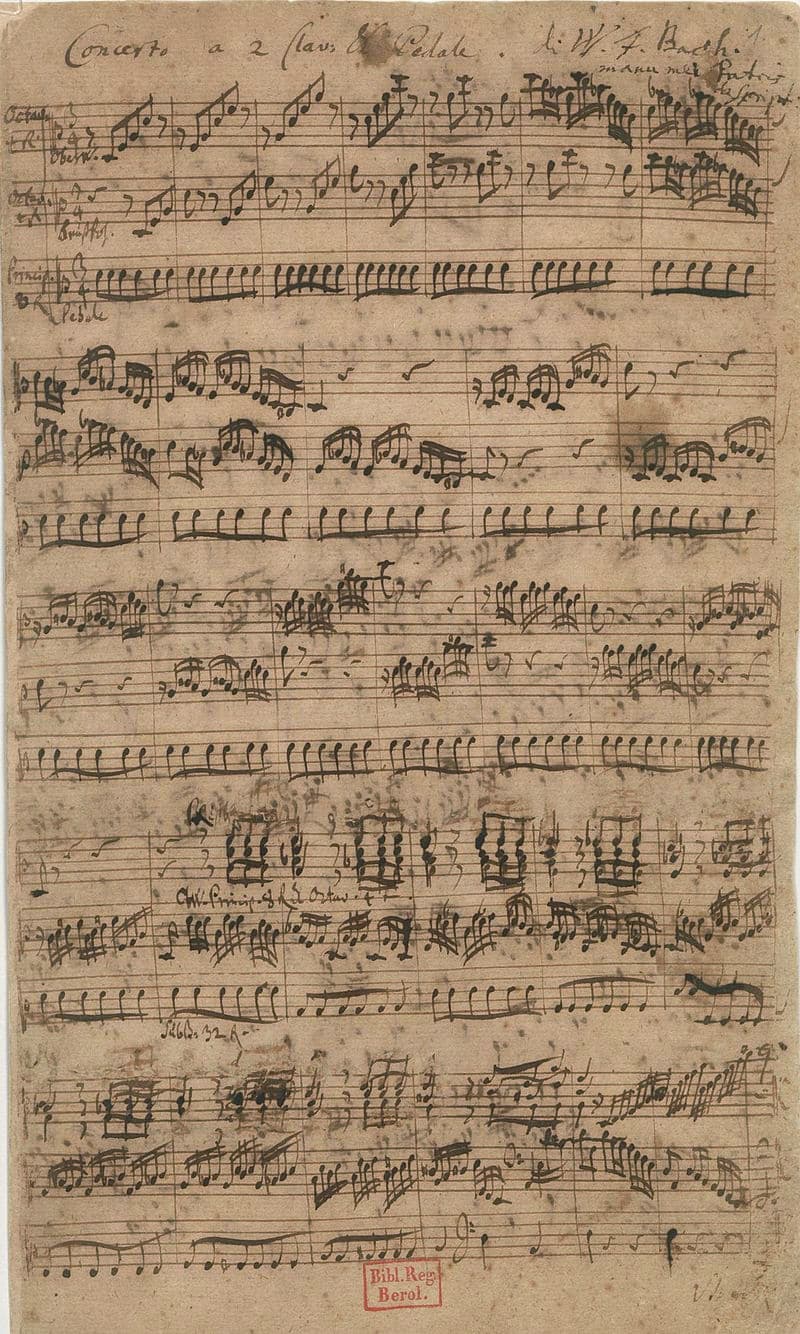

Bach first came into contact with the music of Vivaldi during his tenure as organist at the court of Duke Wilhelm Ernst in Weimar. The young Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar had spent two years in the Netherlands, and he presumably brought back a copy of “L’estro armonico” to Weimar. Most likely, Bach produced the majority of his transcriptions between 1713/1714, including the Vivaldi Op. 3, No. 3, 9, and 12 for harpsichord. The double violin concertos Op. 3, No. 8 and 11 were arranged for the organ, and scored for two manuals and pedal. For his Vivaldi transcriptions, Bach fully respected the original compositions. Reluctant to introduce any structural alterations, he even literally transferred passages idiomatic to the violin. However, by filling out the parts with small canons, motivic references and rapid bass passages, Bach made sure that his personal musical signature would be instantly recognizable. These transcriptions are hardly Bach’s greatest works for the keyboard; however, “they give testimony to the composer’s heightened interest in the Italian style.”

Johann Sebastian Bach: Organ Concerto in A minor, BWV 593 after Vivaldi RV 522

Autograph score of the first movement of BWV 596, Johann Sebastian Bach’s transcription of Vivaldi’s double violin concerto Op.3. No.11

Let’s stay with Johann Sebastian Bach for a while longer, and listen to a much later arrangement of Vivaldi’s Op. 3, No. 10 for 4 harpsichords. According to scholars, it has been dated to Bach’s period in Leipzig, probably originating in the late 1720s or early 1730s. Bach was a very practical man, and there was an unrelenting demand for new works. As such, he produced arrangements for special occasions and immediate consumption. His two concertos for three harpsichords, for example, are said to have been written for performance by himself and his two oldest sons. We don’t know if the concerto for 4 harpsichords was also a family affair, but once again, he followed the Vivaldian model very closely, “measure for measure, harmony for harmony, and theme for theme, but not quite note for note.” The Bach transcriptions were first published in the 1850s and described “after Vivaldi.” The question of authorship was not seriously raised until 1910, and it sparked a revival of Vivaldi’s music.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Concerto for 4 harpsichords, BWV 1065 after Vivaldi RV 580

Vivaldi dedicated his “Harmonic Inspiration” to the highly influential Ferdinando de Medici, son of Cosimo III. He is primarily remembered as a patron of music, having sponsored Handel, Pasquini, Veracini, Casini, and both Scarlattis. And let’s not forget that his greatest gift to the musical world was his patronage of Bartolomeo Cristofori, who was given sufficient time and plenty of money to invent the pianoforte. The Prince of Tuscany, often described as “The Orpheus of Princes”, had a fine singing voice, played the harpsichord and various string instruments, and was supposedly highly skilled at writing counterpoint. Apparently, he was known for his ability to play a piece of music at sight and then repeat it faultlessly without looking at the music. He was also famous for hosting lavish musical entertainments at his villa in Pratolino and even built a theatre for his annual operatic productions. The Prince of Tuscany greatly enjoyed his dalliances with men and women alike, and he died prematurely in 1713, presumably from syphilis.

Antonio Vivaldi: “L’estro armonico,” Op. 3, No. 2 (RV 578) (Arranged for chamber ensemble) (Armoniosa)

Niccolò Cassana: Ferdinando de’ Medici, Grand Prince of Tuscany

A scholar writes, “there is no evidence that the dedication of the concertos to the Medici Prince bore any reciprocal fruit for Vivaldi. However, there can be no doubt that the publication of these works significantly elevated Vivaldi’s status as a composer and within two years, Vivaldi had secured commissions to provide an opera and an oratorio for performances in Vicenza.” The collection that Vivaldi put together for Roger was designed to impress with its diversity, both in style and scoring. The composer drew on more than ten years of experiments with concerto form, introducing “a lyricism and drama that had previously belonged to the opera house.” It is not a chronological collection but rather a complex arrangement designed to show a maximum of variety if the set is played as a whole. In addition, as a scholar wrote, “these concertos provided the rules from which such theoretical writers as Quantz, Marcello and Mattheson judged and advised other composers.” The pedagogical aspects of “L’estro armonico” have carried well into the 20th century, as Shinichi Suzuki made the collection a cornerstone of his teaching method that parallels the linguistic environment of acquiring a native language.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Antonio Vivaldi: “L’estro armonico,” Op. 3, No. 6 (RV 356) (Arranged for Mandolin) (Avi Avital, mandolin; Venice Baroque Orchestra)