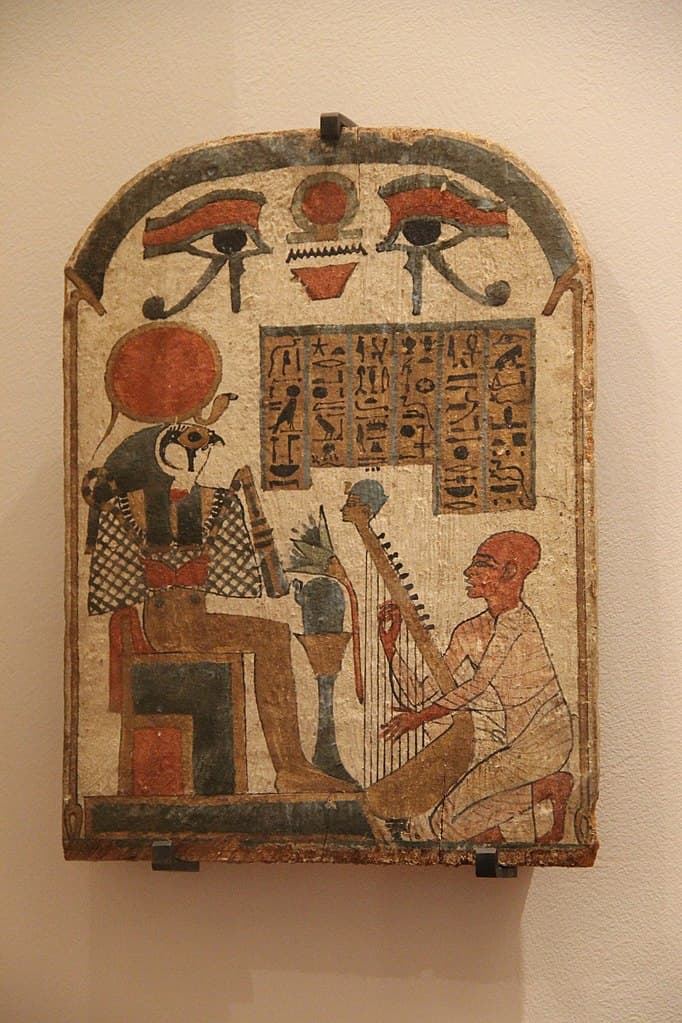

Once you get beyond banging two rocks together (percussion), one of the oldest instruments next invented was the harp. It’s a very simple concept of a frame with differing lengths of strings stretched across to create the pitches. This may have developed from early weapons, such as the bow, and we find mention of harp-like instruments from the most ancient of civilizations: Greek, Assyrian, and Egyptian.

Harper, Stele of Djedkhonsouioufânkh, 1069–664 BC

Harps remained rather simple until a development in 1720 by Jacob Hochbrücher (ca 1673–1763) changed everything. His ‘single-action harp’ added 7 pedals to the instrument so that while playing the instrument, the pitch of the strings could be changed. A complex mechanism runs from the pedals, up the front column of the harp and connects to the strings for a certain pitch: the C-pedal affects all the C strings, etc.

Single-Action Harp in Spruce, 21st century (Mürnseer Musikinstrumentbau)

Before that change, the most prominent use of a harp or a harp-like instrument was in Monteverdi’s opera L’Orfeo, since the leading man was a string player – in art, this could be anything from a harp to a lyre to a violin.

Louis Doukis: Dibutade (Butades) (Orpheus and Eurydice), 1826

By the 1720s, Handel was including harps in his oratorios, and in 1778, Mozart wrote his Concerto for Flute and Harp.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Concerto for Flute and Harp in C Major, K. 299 – I. Allegro (Jiří Válek, flute; Hana Mullerová, harp; Capella Istropolitana; Richard Edlinger, cond.)

The harp was always limited by tuning until 1810 when the French instrument maker Sébastian Érard created the double-action harp, which was fully chromatic. Every note of the scale was available, freeing the harps to take on more adventurous music.

Érard Double-Action Harp, 1810–1830 (Milan: Castello Sforzesco)

Closeup of the pedals and dynamic openings

If you look at the pedals, you’ll see that there’s a two-step zig-zag for altering the string’s pitches, plus an additional pedal that controls the doors on the back of the body to regulate the dynamics of the instrument.

The development of the double-action made the harp a favourite instrument not only in France but also worldwide. Harps were not only used for sonatas and concertos but also chamber music and small ensemble music of all combinations.

Jan Ladislav Dussek (1760–1812) had a mother, a mistress, and a wife who were all harpists, and starting in the 1790s when he was in London, he started writing sonatinas, sonatas, and concertos for the harp.

Jan Ladislav Dussek: Harp Sonata No. 2, Op. 34 – I. Allegro con spirito (Roberta Alessandrini, harp)

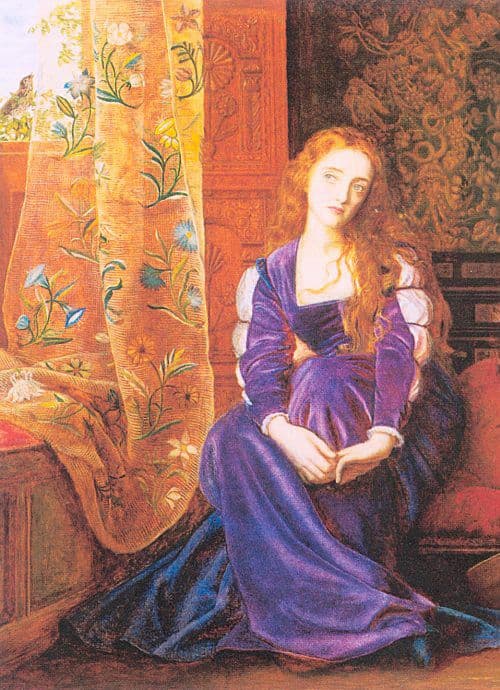

Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924) wrote his Une châtelaine en sa tour, Op. 110, in 1918, based on a poem that he’d set to music in 1891 from Paul Verlaine’s La Bonne chanson collection: ‘Une sainte en son Auréole’. The poem evokes a distant past: ‘A Saint in her halo, | A Chatelaine in her tower, | All that the |Human word of grace and love contains’, and Fauré’s setting gives us a complex set of variations, all evoking grace and love with a soft quality sustained by the seemingly golden notes.

Arthur Hughes: The Pained Heart, ca. 1867

Gabriel Fauré: Une châtelaine en sa tour, Op. 110 (Anne-Sophie Bertrand, harp)

Some of the most demanding harp pieces of the early 19th century came from the pen of English composer Elias Parish Alvars (1808–1849). He toured Europe extensively before becoming a harpist at the Vienna Opera in 1836 and a chamber harpist to the Emperor of Austria in 1847.

Parish Alvars wrote over 80 works for solo harp, and developed extended techniques for the instrument, integrating pedaling and fingering skills, for example. In this work, Sérénade, the challenge comes at the beginning and the ending where one hand has to play harmonics while playing chords in the other.

Elias Parish Alvars: Sérénade, Op. 83 (Phyllis Schlomovitz, harp)

Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868) was far better known for his operas than for his harp music but a brief work he wrote in 1853 for the harpist Contessa Rita Perozzi, simply entitled Allegretto, challenges its player not with technical problems but with its ornamented lyrical theme.

Gioachino Rossini: Allegretto (Paola Perrucci, harp)

Belgian harpist Alphonse Hasselmans (1845–1912) became professor of harp at the Paris Conservatoire in 1884 and held the position until his death nearly 30 years later. He was a primary influence on the 20th century harp school in France and his virtuosic performances inspired not only other performers but also composers to write for him. His own compositions were designed to expand the technical requirements for performers and his piece, La Source, with its constant arpeggios evoking a flowing stream was their test of a performer.

Flowing Stream (Photo by Robert Harmon)

Alphonse Hasselmans: La Source, Op. 44 (Floraleda Sacchi, cond.)

Nino Rota (1911–1979) started composing at age 8 and made his name with his many film scores. He also wrote operas, symphonies, and even a harp concerto. His 1945 Sarabanda e toccata for solo harp mixes a Classical style with modern harmonies, bringing the harp into the 20th century.

Nino Rota: Sarabanda e Toccata – Toccata (Elisa Netzer, harp)

Marcel Grandjany (1891–1975) was a student at the Paris Conservatoire, winning the Premier Prix in 1905. When he moved to the US in the mid-1930s, he taught at some of the leading North American conservatories, including Juilliard, The Manhattan School of Music, and the Montréal Conservatoire. This work from 1953 was Grandjany’s attempt at building up the solo harp repertoire, which he felt had languished in the 20th century.

Marcel Grandjany: Fantasy on a Theme of Haydn, Op. 31 (Xavier de Maistre, harp)

Its title evoking words from a letter that Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother, And Then at Night I Paint the Stars…, is Canadian composer Kelly-Marie Murphy’s piece written on commission by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and the Toronto Symphony Orchestra on the retirement of their principal harpist, Judy Loman. The third movement, Scintillation, takes its title from a work by another harp composer, Carlos Salzédo, and is in the form of an extended cadenza.

Van Gogh: The Starry Night, 1889 (New York: Museum of Modern Art)

Kelly-Marie Murphy: And then at night I paint the stars… – III. Scintillation (Judy Loman, harp)

One last work is Stephen Hodel’s Toccare. The composer considered that the harp was one of the few instruments that is played by physically touching the instrument with one’s hands – no bow or mallet lies between the performer and the strings. The sound you hear at the beginning can be equated to the performer warming up her instrument: ‘touching the soundboard, randomly moving the pedals up and down or hitting and scratching the strings’, all actions that produce sound from the waiting instrument.

Stephan Hodel: Toccare (Elisa Netzer, harp)

As old-fashioned as a harp may seem, modern composers’ willingness to write for the instrument definitely makes it timeless. Its mechanical developments, starting with the ability to change pitch without stopping playing (single-action harp) and then with its ability to play any pitch required (double-action harp) made it an instrument that could keep up with the composer’s most stringent requirements or his wildest imagination.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter