The Reformation and Counterreformation of the 16th and 17th centuries had a decisive impact not only on the architecture of the time, moving from the harmony and balance of the Renaissance to the painted heavens, extreme ornamentation and disturbance captured in the concave and convex form of the Baroque, but was also replicated in the musical forms of the opera and the art of the castrati singers of the period. In church building, the basilica form was resurrected, not only bringing public and priests into a shared space, but changing the church service to a more participatory experience, in which music, and particularly the organ, played a significant part.

The Reformation and Counterreformation of the 16th and 17th centuries had a decisive impact not only on the architecture of the time, moving from the harmony and balance of the Renaissance to the painted heavens, extreme ornamentation and disturbance captured in the concave and convex form of the Baroque, but was also replicated in the musical forms of the opera and the art of the castrati singers of the period. In church building, the basilica form was resurrected, not only bringing public and priests into a shared space, but changing the church service to a more participatory experience, in which music, and particularly the organ, played a significant part.

Bach : Passacaglia and Fugue in C-Minor

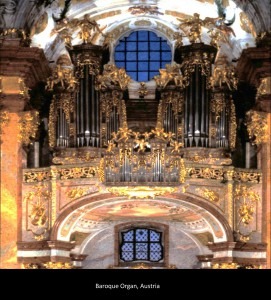

In Germany, profound differences developed between the churches and organs of the Protestant north and Catholic south. In Southern Germany and Austria, organs were seen as decorative elements within the Baroque decoration of the church, to the point that the sound qualities of the instrument were sacrificed in order for the organ to fit into a specific architectural space. Here the organ disappears in the overwhelming Baroque decoration and is considered nothing but a theatrical element in the ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (the total work of art).

The most famous organ builders and greatest organs were all in northern Europe – for example, Arp Schnitger, who built the great organ of St. Jacobi in Hamburg in 1693, where Johann Sebastian Bach applied for the position of organist in 1720 (and was rejected), Zacharias Hildebrandt and Gottfried Silbermann from Saxony. Silbermann organs were considered masterpieces not only by J.S. Bach, who was often asked to test these new organs as to their ‘lung capacity’, their potential wind and sound qualities, but to this day are considered some of the best organs ever built. Baroque organs were tuned not in a ‘tempered’ fashion, but ‘mitteltőnig’ (middle-tuned, i.e. one tone above the normal ‘A’), resulting in a rich, warm and resonant tone. They were the perfect instruments for Bach to explore extraordinary sound possibilities and to create many of his organ and choral masterpieces. In the service of the Duke of Saxony-Weimar from 1708 until 1717, he composed some of the organ music most familiar to us today – the Toccata and Fugue in D-Minor, the Passacaglia and Fugue in C-Minor, etc.

The most famous organ builders and greatest organs were all in northern Europe – for example, Arp Schnitger, who built the great organ of St. Jacobi in Hamburg in 1693, where Johann Sebastian Bach applied for the position of organist in 1720 (and was rejected), Zacharias Hildebrandt and Gottfried Silbermann from Saxony. Silbermann organs were considered masterpieces not only by J.S. Bach, who was often asked to test these new organs as to their ‘lung capacity’, their potential wind and sound qualities, but to this day are considered some of the best organs ever built. Baroque organs were tuned not in a ‘tempered’ fashion, but ‘mitteltőnig’ (middle-tuned, i.e. one tone above the normal ‘A’), resulting in a rich, warm and resonant tone. They were the perfect instruments for Bach to explore extraordinary sound possibilities and to create many of his organ and choral masterpieces. In the service of the Duke of Saxony-Weimar from 1708 until 1717, he composed some of the organ music most familiar to us today – the Toccata and Fugue in D-Minor, the Passacaglia and Fugue in C-Minor, etc.

Bach : Die Kunst der Fuge

Bach : Die Kunst der Fuge

In his early organ works, Bach was mainly influenced by Reineken and Buxtehude, but in Weimar he heard and played the music of the new Italian masters, (e.g. Vivaldi, Corelli and Albinoni), applying his own counterpoint skills to their fast themes. His Orgelbűchlein (Little Organ Book), a set of short, imaginative organ preludes, each based on a melody of a standard Lutheran chorale, unravels Bach’s ‘architectural’ musical language, with rhythm and the turn of phrase associating with specific ideas in the chorale text. His intellect and mathematical thinking is evident in all of these works, as well as in Das Wohltemperierte Klavier (The Well-tempered Clavier) and Die Kunst der Fuge (The Art of the Fugue).

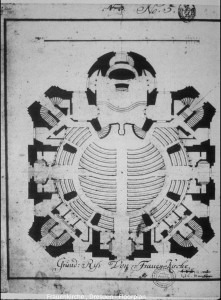

The newly built Baroque churches such as the Frauenkirche in Dresden (Church of Our Lady) were also architecturally suited to these new organs as their sound could fill their circular space of the basilica, within which the congregation now participated actively.

The newly built Baroque churches such as the Frauenkirche in Dresden (Church of Our Lady) were also architecturally suited to these new organs as their sound could fill their circular space of the basilica, within which the congregation now participated actively.

In comparison to the organs in the south, Silbermann organs appear rather plain visually, and very similar to each other. Their quality lies in the use of the best and most expensive materials, extraordinary workmanship and execution, with no sacrifice made just to accommodate a specific architectural space. The Silbermann organ of the Schloßkirche in Dresden, Germany, recently restored to its original Baroque sound, was one of his last and largest works, with 47 registers divided over three manuals and a pedal.

In comparison to the organs in the south, Silbermann organs appear rather plain visually, and very similar to each other. Their quality lies in the use of the best and most expensive materials, extraordinary workmanship and execution, with no sacrifice made just to accommodate a specific architectural space. The Silbermann organ of the Schloßkirche in Dresden, Germany, recently restored to its original Baroque sound, was one of his last and largest works, with 47 registers divided over three manuals and a pedal.

Over the course of the following centuries and particularly during the Romantic period of the 19th century, the tonality of many Baroque organs had been changed according to the reigning sound concepts of the time. Today there is increased interest in the restoration of the original tonal qualities of Baroque organs. Master organ builders such as Wolfgang Rehn, Director of Organ Restoration at Kuhn Orgel, GmbH, Switzerland, are continuing to make a number of such restorations in several European countries. Hearing Baroque organ music on Baroque organs in Baroque churches is an experience never to be forgotten.

Over the course of the following centuries and particularly during the Romantic period of the 19th century, the tonality of many Baroque organs had been changed according to the reigning sound concepts of the time. Today there is increased interest in the restoration of the original tonal qualities of Baroque organs. Master organ builders such as Wolfgang Rehn, Director of Organ Restoration at Kuhn Orgel, GmbH, Switzerland, are continuing to make a number of such restorations in several European countries. Hearing Baroque organ music on Baroque organs in Baroque churches is an experience never to be forgotten.

You May Also Like

-

Klais Organs: The Power behind the Throne The age-old craft of organ building is a highly creative profession that demands constant analysis of tradition, while simultaneously keeping abreast of the latest technical, practical and aesthetic developments.

Klais Organs: The Power behind the Throne The age-old craft of organ building is a highly creative profession that demands constant analysis of tradition, while simultaneously keeping abreast of the latest technical, practical and aesthetic developments. -

Organ Restoration — A Lifelong Calling Master Organ builder Wolfgang Rehn, (who, incidentally, happens to be my very own brother) formerly director of organ restoration at Kuhn Organ Builders

Organ Restoration — A Lifelong Calling Master Organ builder Wolfgang Rehn, (who, incidentally, happens to be my very own brother) formerly director of organ restoration at Kuhn Organ Builders -

Women in Baroque Music "London Festival of Baroque Music 2015" Women in music, either as composer, performers, or inspirational figures, are never celebrated enough.

Women in Baroque Music "London Festival of Baroque Music 2015" Women in music, either as composer, performers, or inspirational figures, are never celebrated enough. - Corelli and JS Bach:

The Musical and Architectural Baroque Style Arcangelo Corelli and Johann Sebastian Bach were two of the composers most familiar to me in my youth...

More Arts

- Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870)

“Music is the only noise for which one is obliged to pay” We look at his collaborations with composers on operas and more! - “In the Hall of the Mountain King”

Henrik Ibsen in Music "Peer Gynt goes very slowly. It is a horribly intractable subject except for a few places… " - Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

“No art could be less spontaneous than mine” Look at Degas' burning passion for opera from his artwork - Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669)

Born on 15 July Learn about his ancestry, childhood and more

Can you do fun facts about baroque era pipe organ please and thank you