Time Capsules can be a wonderful thing. Many people and organizations have gone through the trouble of intentionally assembling a cache of goods or information as a method of communication with future people. It gets even more interesting when such time capsules are inadvertently compiled and handed from generation to generation without knowledge of its content. Such was the case with a box of 88 invaluable original art works delivered to the Viennese art critic and music lover David Josef Bach (1874-1947) on the occasion of his 50th birthday in 1924.

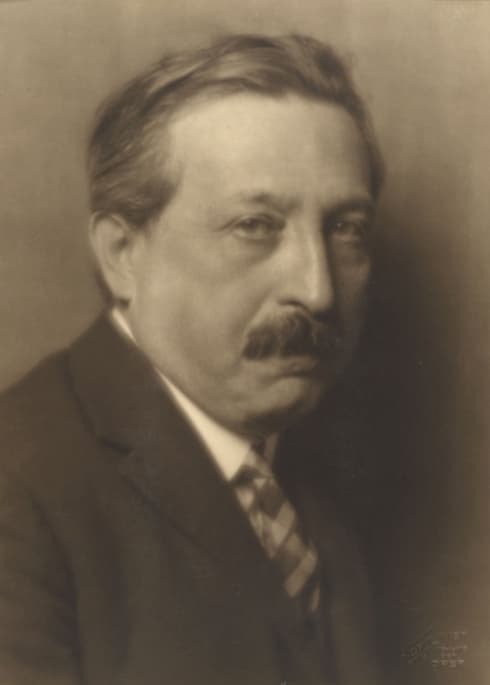

David Josef Bach

Bach had managed to bring this treasure drove to England in 1939, where it sat undisturbed, first in a garage and then in a bank vault for decades. The python skinned box designed by architect Josef Hoffmann was “rediscovered” in 1999 and contains contributions from Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Karl Kraus, Arthur Schnitzler, Oskar Kokoschka, Carl Moll, and many other leading artists of the time.

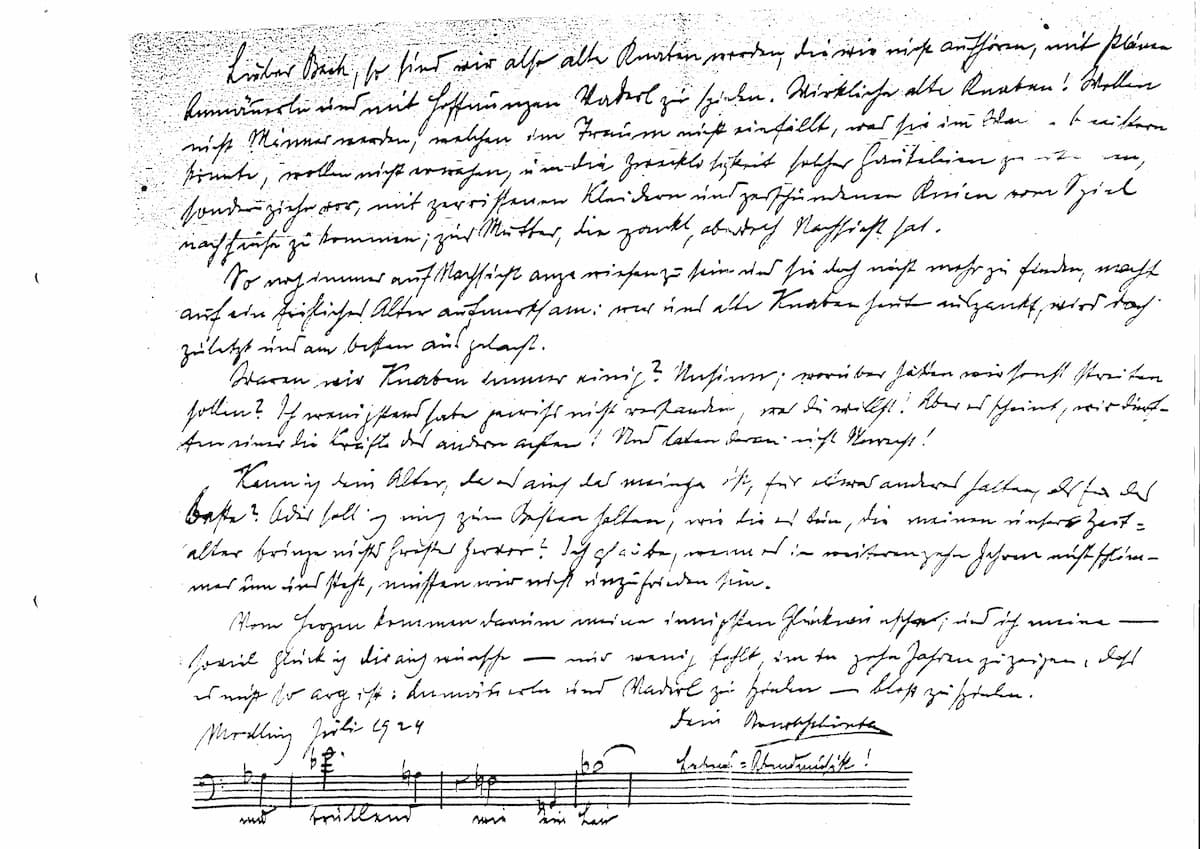

Letter from Arnold Schoenberg

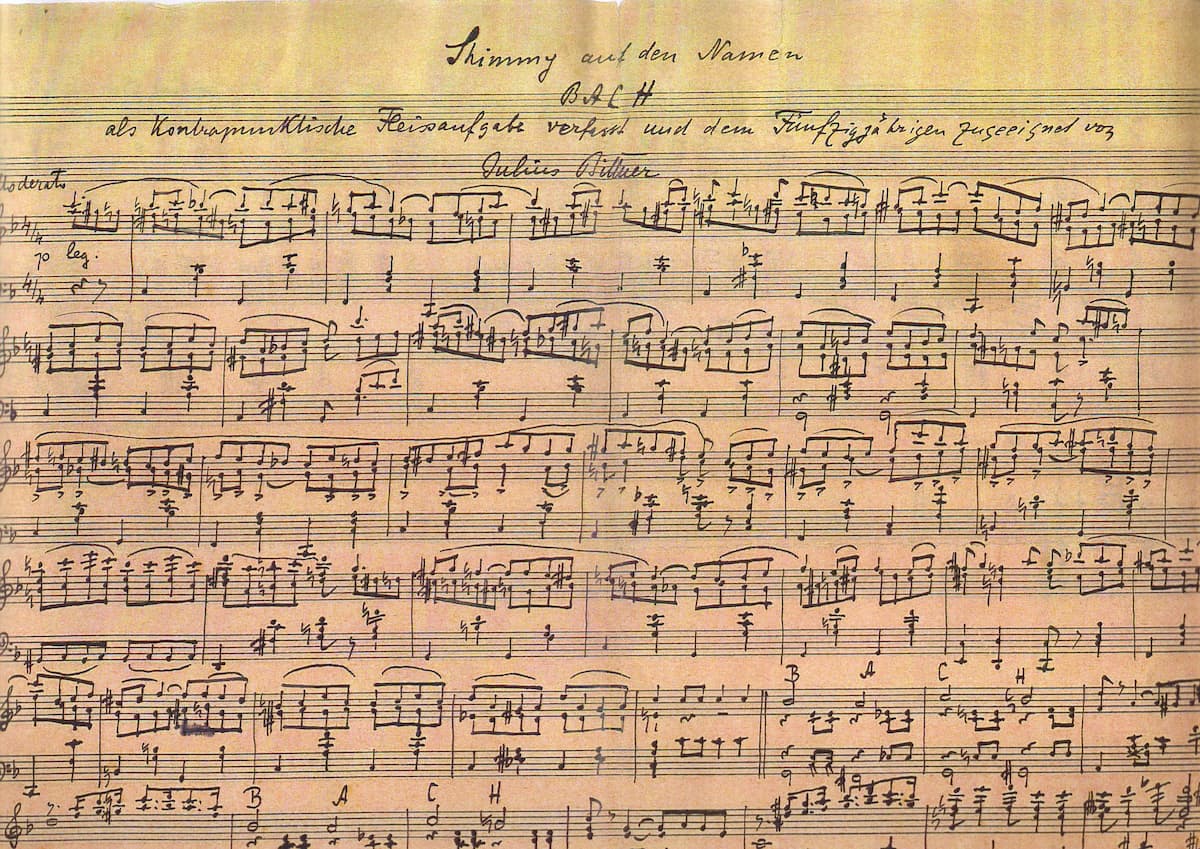

In addition, we find musical greetings and musical extracts by Richard Strauss, Alexander Zemlinsky, Franz Lehàr, Alban Berg, Béla Bartók, Julius Bittner, Hans Eisler, Zoltán Kodály, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Franz Schmidt, Josef Suk, Georg Szell, Anton Webern, Karl Weigl and Arnold Schoenberg.

Josef Suk: Asrael, Op. 27 “Part 1” (Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra; Libor Pešek, cond.)

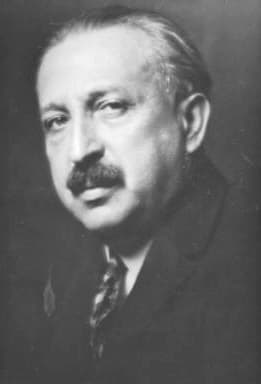

David Josef Bach

For most of us today, David Josef Bach is not a household name. Yet, in early twentieth-century Vienna, he was an important and highly influential figure in the city’s cultural life. Born in what is now Lviv in the Ukraine, his family moved to Vienna and the boy became a close friend of the young Arnold Schoenberg. The buddying composer later named him as one of three friends who “greatly influenced me in my youthful exploration of music and literature.” Bach was appointed music critic at the Arbeiter-Zeitung (Worker’s Newspaper) in 1904, and in his column he was highly supportive of contemporary music. He also became a staunch supporter of Schoenberg and Mahler, and he was one of the earliest members of the Vienna Psychoanalytical Association, which met under the guidance of Sigmund Freud. Given the emerging explosive political situation in Vienna, Bach was openly denounced as “part of a Jewish conspiracy to undermine traditional Austrian culture.”

Erich Wolfgang Korngold: Piano Concerto, Op. 17 (Howard Shelley, piano; BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Matthias Bamert, cond.)

A musical greeting from Alban Berg

David Josef Bach had studied to become a linguist, philosopher, and mathematician. His greatest passion, however, was for music. An enthusiastic and active socialist, Bach brought music to the people by making the arts accessible to the working classes. In 1905, he initiated the “Arbeiter Sinfonie Konzerte” (Workers’ Symphony Concerts).

Through their Trades Unions, workers could acquire discounted tickets for orchestral concerts. In addition, that included access to theatre productions at the Viennese Kunststelle (Vienna Arts Centre), where Workers were able to attend performances of Goethe, Schiller, Shakespeare, John Galsworthy, and George Bernard Shaw. There can be no doubt that David Josef Bach “was arguably the first man to make high art accessible and affordable to the Viennese proletariat.” Arnold Schoenberg wrote, it was “D.J. Bach who furnished my character with the ethical and moral power needed to withstand vulgarity and commonplace popularity.” And in his birthday greeting Schoenberg writes, “So we have become old boys… we don’t want to grow up and become the sort of men to whom nothing happens in dreams that we cannot grasp when awake… Whoever now scolds us old boys will ultimately be held up to ridicule.”

Zoltán Kodály: Psalmus Hungaricus, Op. 13 (Raymond Nilsson, tenor; London Philharmonic Choir; London Philharmonic Orchestra; János Ferencsik, cond.)

Julius Bittner: Bach Shimmy

Bach became editor-in-chief of the literature and art section of the Arbeiter-Zeitung in 1917, and soon thereafter, highly influential politically. He was appointed Director of the “Social-Democratic Arts Council” and in charge of cultural events within a program to reform public housing, social and health services, education, and financial policies termed “Red Vienna.” Bach continued to organize readings, theatre plays and concerts, and to help working-class audiences to be better prepared, he published a monthly arts magazine. He also founded the amateur “Vienna Choral Society,” and the “Workers’ Music Conservatoire.” Bach held a unique position in the cultural politics of Vienna, as “he attempted to create a cultural consensus during a time of increasing political polarization.” His unique status is beautifully reflected in his “Birthday Kassette” bringing together a great diversity of contributors from all political and artistic backgrounds. It is a truly unique time capsule of 1924 Viennese cultural life.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Béla Bartók: Piano Concerto No. 1, “Allegro molto” (Alfred Brendel, piano; BBC Symphony Orchestra; Bruno Maderna, cond.)