Dmitri Shostakovich was born in 1906 in St. Petersburg, Russia. He was an extraordinary talent who spent his entire creative life interacting with the Soviet regime, and his dark soulful works are favorites in the classical music world.

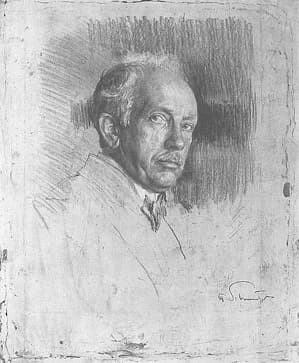

Shostakovich playing at Madison Square Gardens

Here are a few facts about Shostakovich’s life and career:

- Shostakovich lived through the tumultuous historic periods of a few Soviet periods, including Joseph Stalin’s bloody reign.

- He faced immense pressure to conform to the state’s demands for “socialist realism” in his music. This led to periods of alternating praise and criticism from authorities.

- He was immensely prolific. He wrote fifteen symphonies, fifteen string quartets, six concertos, over two dozen orchestral suites, and so much more.

- He liked referencing himself in his music. One of his most famous musical signatures is something known as the DSCH motif, which is a translation of letters from his name into a series of notes. The DSCH motif appears in multiple works.

- People still argue today about how much of his work was sarcastic or held double meanings.

Intrigued? If so, here are ten of Shostakovich’s works to get you started.

Symphony No. 1 in F minor (1923–1925)

Shostakovich wrote his first symphony at the age of nineteen. It was his graduation piece when he left the Petrograd Conservatory (previously the St. Petersburg Conservatory).

When his aunt heard it performed, she was surprised to hear that Shostakovich had included excerpts of compositions from his childhood in the symphony.

It was received incredibly well and continues to be performed to this day: impressive work for a teenager!

Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (1930-34)

This opera tells the story of an unhappily married woman named Katerina who is raped, commits adultery, and becomes a killer: intense subject matter for a Soviet composer to take on in a regime-approved way. It didn’t help that the music was notably graphic.

The opera was a hit for two years until 1936, when Stalin attended a performance. Disgusted, he departed halfway through the performance.

On cue, the Soviets denounced Shostakovich in the magazine Pravda, and his life was changed forever. People reportedly crossed the street to avoid being seen talking to him. Shostakovich would have to work hard – and smart – to avoid the gulag and to get back into the Party’s good graces.

Symphony No. 5 in D minor (1937)

Shostakovich’s next big creative task was overwhelming. He had to please Stalin while still fulfilling himself creatively.

His response to the denunciation was to write his fifth symphony. It is immediately accessible to lay audiences, but it also has a tinge of acid to it.

Listen to the ending of the final movement (48:57 in the video above). Some people have read this as an unalloyed pro-Soviet celebration. Others read it as a parody of celebration.

What’s the correct interpretation? We can’t know for sure, exactly. Nothing with Shostakovich is ever simple.

Symphony No. 7 in C major (1941)

World War II began in 1939. In 1941, Hitler began invading the Soviet Union.

The terrible siege of Leningrad began in September 1941 and did not end until January 1944, killing an unimaginable 1.5 million people.

Shostakovich was in the middle of writing his seventh symphony when the siege began. In between stints spent in bomb shelters, he went on the radio to say, “An hour ago I finished the score of two movements of a large symphonic composition. If I succeed in carrying it off, if I manage to complete the third and fourth movements, then perhaps I’ll be able to call it my Seventh Symphony. Why am I telling you this? So that the radio listeners who are listening to me now will know that life in our city is proceeding normally.”

Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Khachaturian

With his seventh symphony, Shostakovich became a national hero. He wrote much of the work in Leningrad, but it was finished after he and his family were evacuated.

The world premiere was given “in exile” in the city of Kuybyshev, where the Shostakoviches were evacuated to. The score was then sent via microfiche all around the world and played in various Allied countries, including America, in 1942.

By the time it got to St. Petersburg, only fifteen members of that city’s orchestra were still alive or in town. Nevertheless, they performed the symphony on 9 August 1942. Loudspeakers broadcast the symphony to the front lines to demoralize the Nazis.

On a sheerly musical level, this may not be Shostakovich’s greatest symphony. But it is a gripping work and an important highlight of his career.

Violin Concerto No. 1 (1947-48)

Even though he had now become a national hero, Shostakovich was very aware that his position was precarious. Circumstances could change at a moment’s notice, just as they had during the Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District fiasco.

During this time, he wrote a dark, aggressive violin concerto that he knew Soviet officials would not take kindly to.

He collaborated with his friend, master violinist David Oistrakh, in secret on this concerto. Both were aware the political climate would have to change before it could be brought to the concert stage.

Eventually, restrictions on artists loosened somewhat, and Oistrakh and Shostakovich were able to premiere the violin concerto publicly in 1955.

It is a deeply emotional work from start to finish, and the voice of the solo violin is agonized, giving a glimpse into how psychologically difficult these circumstances must have been.

24 Preludes and Fugues (1950-1951)

In 1950 Shostakovich embarked on an ambitious project, an homage to Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier, which features 48 preludes and fugues.

Shostakovich exercised his music geekery here, paying tribute to Bach by using similar notes and similar rhythms. That said, he never indulged in cheap imitation, and the work is unmistakably his.

Waltz No. 2 from Suite No. 1 for Variety Orchestra (1955-56)

This suite contains some of Shostakovich’s most popular music. This movement is the famous waltz.

The instrumentation in this suite is unusual, featuring saxophone, accordion, and guitar, which would make the music sound at home in a grandiose, unhinged carnival.

Cello Concerto No. 1 in E♭ major (1959)

This concerto features an unusual structure. It is in four movements, instead of the traditional three. The third movement does not feature any orchestral accompaniment at all, and is instead a solo for the soloist. And the whole work is dominated by an insistent four-note theme that returns again and again in new guises.

This four-note theme found its way as a motif in several works and is one of Shostakovich’s compositional hallmarks. It’s called the DSCH motif and is based on his name – D, Es (i.e., E-flat), C, and B. (In German, B-natural is known as H.)

Musical cryptography like this has been around for a long time, but it gains a special poignancy in the context of the brutal Soviet regime when so many ideas and identities had to be hidden.

String Quartet No. 8 in C minor (1960)

During all of this political upheaval, Shostakovich often found himself making his most honest confessions in chamber music rather than large symphonic works.

One of his most stunning works is his eighth string quartet, which he wrote in just three days in the summer of 1960. Some believe it was meant to be a final testament before a suicide.

Whether that’s true or not, it was clearly deeply personal. It includes the DSCH motif in each of its four movements, and quotes a variety of his earlier works, like his first and fifth symphonies, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, as well as the cello concerto.

This violent, devastating, heartbreaking quartet is legendary. There’s nothing else in his output – or any composer’s outlet – quite like it. It will haunt you.

Viola Sonata (1975)

The viola sonata was one of Shostakovich’s final works. The dedicatee was violist Fyodor Druzhinin, who the composer consulted in his final days.

The timeline of its creation is sobering:

On July 1, 1975, Shostakovich wrote, wondering if a particular technique was doable on the instrument.

On July 4, he warned that his health was declining, and he wasn’t sure if he’d be able to continue working.

He finished the sonata on July 5. There were delays in copying it, but Druzhinin finally got a fair copy on August 6.

Shostakovich died on August 9.

Grave of Dmitri Shostakovich © findagrave.com

He looked backwards by, again, quoting many of his older works, including all fifteen of his symphonies, as well as references to Beethoven and Richard Strauss’s Don Quixote. It was a fitting finale to an incredible career.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Emily! Enjoyed the article. Especially the final photo — I spent an entire afternoon in Novodevichy Cemetery looking for it. I ran into Maxim Shostakovich several months later and asked him where his father’s grave was. When he told me I was so depressed. It was in the section of the cemetery I’d just come to when the cemetery closed and I had to leave. So, thank you so much for the photo! I am placing the huge bouquet of flowers I had that day on it in my mind.