Robert Schumann was born in the town of Zwickau in present-day Germany in 1810.

Along with his wife, the great pianist and composer Clara Schumann, he went on to become one of the leading figures of Romantic Era music.

Kriehuber: Robert Schumann (1839)

Here are some facts you should know about his life:

- When Robert Schumann was a child, he loved books just as much as he loved music. Throughout his life, he expressed himself by writing as well as composing.

His family pressured him to study law in Leipzig, but he was never able to fully commit himself to his studies. - In 1829, he began taking piano lessons with a Leipzig teacher named Friedrich Weick. Weick had made his name training his prodigy daughter Clara, who began touring Europe at the age of eleven to serve as a kind of living advertisement for her father’s methods.

- Schumann’s hand was injured during this time, and he had to dial back his performance studies. Instead, he focused on writing and composition.

In 1834, he began a magazine about music called Die Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, or the New Journal for Music. It became an influential outlet. - When Clara was sixteen, she and the twenty-five-year-old Robert fell in love.

Their courtship was rocky due to Friedrich’s harsh disapproval of their relationship, but despite this, they were married the day before Clara’s 21st birthday in 1840. The Schumanns would have eight children together. - During his life, Robert battled increasingly severe mental health issues.

He was well-known for his manic periods, during which he’d write dizzying amounts of music, and his depressive periods, during which he’d write very little at all.

In early 1854, his hallucinations worsened, and he recognized that he was losing touch with reality. He went to an asylum in Bonn and died there two years later, in July 1856. He was only forty-six. - Clara took on the work of raising his children and advocating for his music. She lived for decades more and had a hugely successful performing career. She assured his entrance into the classical music canon and is a major reason why we still hear his music today.

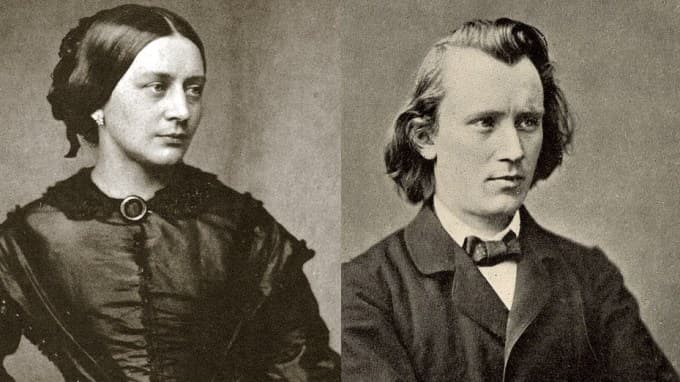

Clara Wieck at 16 years old

Intrigued? Hopefully, because the Schumanns are one of the most interesting couples in classical music history!

So, here’s a tour of ten of Robert Schumann’s best-known works:

Ten Impromptus on a Theme by Clara Wieck (1833)

We’ll start by looking at the earliest artifacts of Robert Schumann’s creative partnership with Clara Wieck.

Clara Wieck was not just a prodigy pianist; she was also a composer, and she composed this melody when she was thirteen.

To show his appreciation for her and her father, Robert composed ten variations on this theme. The work includes the theme, ten variations on it, and a grand Beethoven fugue at the end.

It is youthful, energized, inspired music.

Kinderszenen (“Scenes from Childhood”) (1838)

By 1838, Robert Schumann and Clara Wieck were very much in love, although her father’s disapproval was making their relationship very difficult.

To prove his devotion, Schumann wrote another set of piano pieces Kinderszenen for her to play. There are thirteen pieces here in all. They were inspired by her offhand comment to him that sometimes she felt like he was “like a child.”

The most famous of the thirteen pieces is the seventh, called “Träumerei” or “Dreaming.” It is indeed a very dreamy piece and one of the quiet classics of the Romantic Era piano repertoire.

Kreisleriana (1838)

When composing his piano work Kreisleriana, Schumann took inspiration from an E.T.A. Hoffmann character named Johannes Kreisler, Hoffmann’s alter ego. Kreisler is a composer who has dramatic swings in personality. It’s easy to see why Schumann was attracted to this subject matter!

Schumann was inspired by the idea of multiple personalities residing in one human. He nicknamed two of his own personalities: Florestan was quick and impulsive and extroverted, while Eusebius was slower and dreamier, and introverted. These two personalities appear in the music.

He also threw Clara into the mix, too. “You and one of your ideas play the main role in it, and I want to dedicate it to you – yes, to you and nobody else – and then you will smile so sweetly when you discover yourself in it,” he wrote to her.

Schumann composed this half-hour work in just four days: impressive, of course, but also a sign of how intense his composing hyper fixation could get!

Dichterliebe “A Poet’s Love” (1840)

This would become Schumann’s most famous song cycle. It consists of sixteen songs, with lyrics from poet Heinrich Heine.

The poetry features colorful descriptions of what it’s like to be in love, set to an achingly beautiful, intimate piano accompaniment.

Schumann was overflowing with inspiration on the subject, given that this was the year in which he was finally able to marry Clara.

Somewhat ominously, Schumann ends the cycle with a tragic poem in which the narrator requests a massive casket and seven giants to carry it. “They must carry the coffin and throw it in the sea, because a coffin that large needs a large grave to put it in. Do you know why the coffin must be so big and heavy? I will also put my love and my suffering into it.”

Symphony No. 1 “Spring” (1841)

After his marriage, Schumann was inspired to write his first big work for orchestra.

Clara wrote in her diary, “It would be best if he composed for orchestra; his imagination cannot find sufficient scope on the piano… His compositions are all orchestral in feeling… My highest wish is that he should compose for orchestra—that is his field! May I succeed in bringing him to it!”

Early in 1841, he created his first symphony, which he sketched out in just four days and orchestrated within a few weeks.

The timeline of the programmatic “spring” inspiration is uncertain. Schumann later wrote to a friend, “Could you breathe a little of the longing for spring into your orchestra as they play? That was what was most in my mind when I wrote [the symphony] in January 1841… Further on in the introduction, I would like the music to suggest the world’s turning green, perhaps with a butterfly hovering in the air, and then, in the Allegro, to show how everything to do with spring is coming alive… These, however, are ideas that came into my mind only after I had completed the piece.”

Piano Quintet in E-flat (1842)

Schumann composed this ebullient chamber music work in just a few weeks, another instance of his extraordinary, somewhat unnerving productivity during creative mania.

What’s even more bewildering, given the brilliance of this work, is that Schumann had not composed any chamber music for strings before 1842, and yet he was writing this – one of the classics of the genre – by August.

Although the quintet fairly fizzes with exuberance, it also has its somber moments. The measured funeral march in the second movement (9:35 in the recording above) is particularly stately.

This was one of the many works of Robert’s that Clara championed for decades after his death.

Piano Concerto in A minor (1845)

Schumann’s legendary piano concerto began life as a one-movement fantasy in 1841 (which, predictably, he wrote over the course of just three days).

Clara encouraged him to add more music to it to make it a full-fledged concerto. He did this in 1845, and so the Robert Schumann piano concerto was born.

Clara, of course, performed the premiere of the concerto. That premiere took place in Dresden in December 1845 when she was seven months pregnant with their fourth child.

Cello Concerto in A minor (1850)

The cello concerto also, unsurprisingly, came to life in a very short period of time: only two weeks, in October 1850.

Schumann hated audience applause in between movements, so he decided to write a work in which all the movements flowed into each other without a break. This makes the concerto feel very free and almost like a fantasy.

When Schumann showed the score around to feel the possibility of a premiere, the work was not received well. And, of course, Clara couldn’t advocate for it in the same way she could his piano concertos and chamber music. Accordingly, he never heard it played in his lifetime.

Although it is unusual – some would say enigmatic – this concerto ultimately became one of the pillars of the cellist’s repertoire.

Violin Sonata No. 1 in A minor (1851)

Yet again, here’s a work that was written over the course of just a single week in September 1851. It has since become a classic, but Schumann claimed he didn’t like it very much. That said, it’s important to keep in mind his ever-deteriorating mental health when listening to these works – and reading what he thought about them.

He was having difficulty in his professional life, too, which is perhaps reflected in the sonata’s restless storminess. He had been appointed conductor of the Düsseldorf orchestra, but he wasn’t well-suited for the job and faced constant difficulties there. Things got so bad that he was eventually fired.

Symphony No. 4 (written in 1841; revised in 1851)

In 1853, as Schumann’s mental health was deteriorating, he and Clara met a twenty-year-old composer named Johannes Brahms for the first time. They were both hugely impressed by the young man’s genius. In fact, Schumann saw in him a potential successor. Brahms was hugely inspired by his mentors and accidentally fell in love with Clara.

Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms

After Schumann died in 1856, Clara and Johannes became partners in advocating for Schumann’s music. For years, they worked together on this and other projects, and even after the hint of romance fizzled out, they remained creative soulmates.

However, there was drama when it came time to release the score of Schumann’s fourth symphony. Schumann had written it originally in 1841, then rewritten it in 1851. Late in her life, Clara released an edition, claiming in an introduction that it had only been fully orchestrated in 1851. Johannes, however, had receipts: i.e., the (yes, fully orchestrated) 1841 version, which he vastly preferred to the 1851 version that Clara had chosen to release. Clara was not happy with Johannes!

It is worth listening to both versions of the symphony and keeping in mind what a big impact survivors can have in establishing the reputation of a canonized composer. Which version do you like best?

1841 version:

1851 version:

Conclusion

While he was at the asylum, Robert Schumann was forbidden from seeing Clara. His doctors were afraid that seeing Clara would trigger a dangerous relapse.

However, Brahms came to visit and went back to report to Clara what he could. He also helped out in the household (there were eight kids to look after, including a newborn!), and played piano duos with Clara in the lonely evenings to keep her company.

Finally, Robert’s case became hopeless. He stopped eating and died in July 1856, one of the truly archetypal composers of the Romantic Era.

You can learn more about him in our Robert Schumann tag.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter