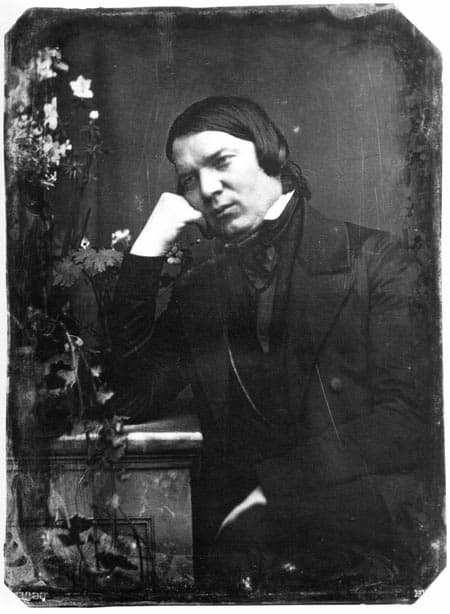

In 1840, Robert Schumann wrote to his beloved Clara, “This ceaseless inner music is almost killing me; I am almost obsessed by it. Oh Clara, what bliss it is to compose for the voice! I have done without it for a long time.” And shortly thereafter he called the twelve songs that make up the Liederkreis Op. 39 “my most romantic music ever, with much of you in it, dearest Clara.”

Robert and Clara Schumann, 1850

Only one year earlier, Schumann had written to a composer and colleague, “Are you perhaps like me, someone who all his life has placed vocal compositions below instrumental music and never regarded them as great art?” What then actually changed Schumann’s mind? In 1839 Schumann was in a legal tussle with Friedrich Wieck over the hand of his daughter Clara. Wick claimed that Schumann was a scoundrel, drunk, and did not make enough money to support his daughter.

Robert Schumann: “Moonlit Night” (arr. J. Starker for cello and piano) (Andrew Joyce, cello; Rae de Lisle, piano)

Year of Songs

Robert Schumann, 1850

To prove to the courts that he could make lots of money in a short period of time, Schumann embarked on his “Year of Song” in 1840. Almost half of the works in this genre were created and published in this short period of time, and Schumann emerged as one of the greatest composers of the 19th century. He shaped the image of the Romantic style in music. Through his efforts, the art song became one of the main pillars of new music.

When Schumann completed the Liederkreis, based on poems written by Joseph von Eichendorff, he was not yet married to Clara. The entire collection of poems is not based on the usual topic of love but on solitude. It is the epitome of lyricism, with the songs describing isolation, premonitions, enigmas, mysteries, and promises of the loss of sensuality and spirituality.

Robert Schumann: “Intermezzo” (arr. clarinet and piano) (Shuhei Isobe, clarinet; Etsuko Okazaki, piano)

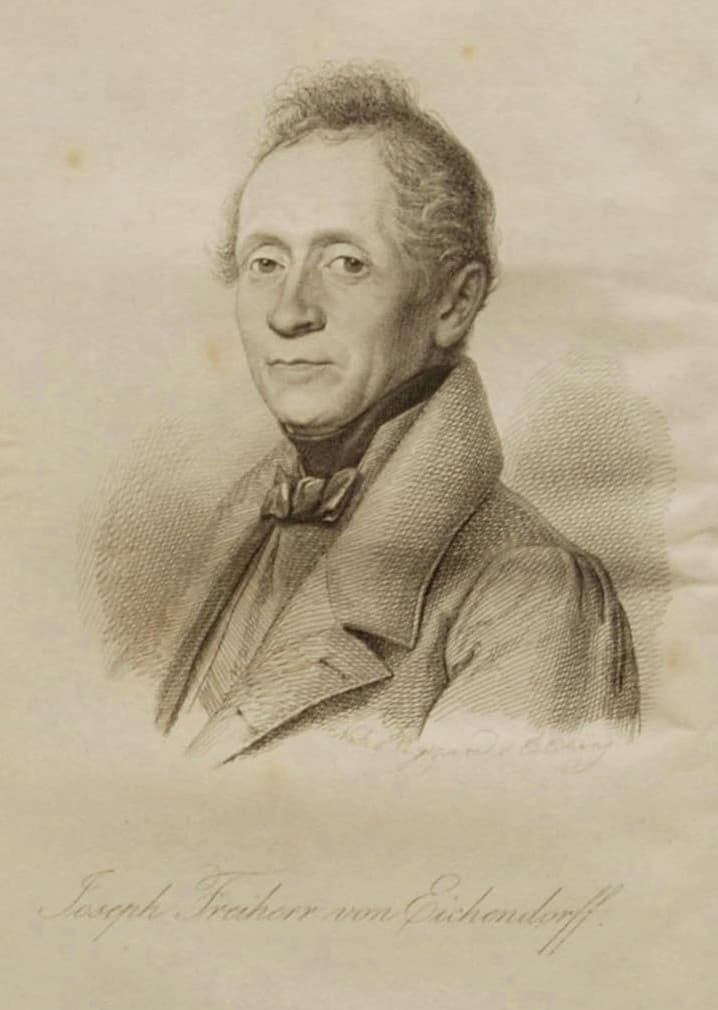

Joseph von Eichendorff

Joseph von Eichendorff

For his Liederkreis, Schumann selected the poetry of Joseph von Eichendorff, who the philosopher Theodor Adorno identified as “a poet of homesickness.” Some basic concepts of Eichendorff’s poetry address the passing of time and nostalgia. Time for Eichendorff “is not just a natural phenomenon but each day and each of our nights have a metaphysical dimension.”

The morning, on the one hand, evokes the impression that “all nature had been created just in this very moment, while the evening often acts as a metaphor for the pondering of transience and death.” Nostalgia, in turn, has been identified with the phenomenon of infinity. Comprised of longing and melancholy, “the inner emotion for longing is to long for, the inner emotion of melancholy is to mourn.”

Robert Schumann: “In a Distant Land” (arr. A Hasselmans for harp) (Antoine Malette-Chénier, harp)

The Poetry

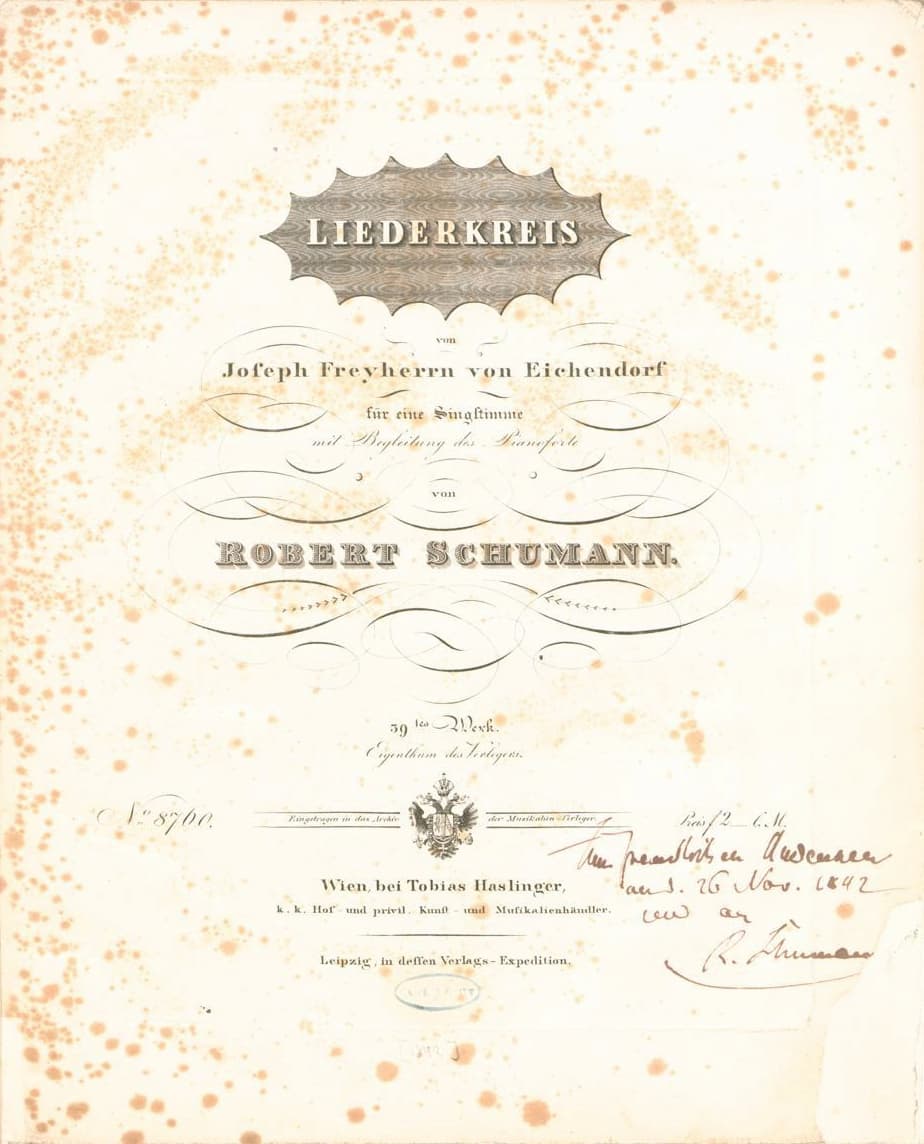

Robert Schumann’s Liederkreis score cover

The poems for the Liederkreis are not strictly a cycle, but an overarching narrative of being in close touch with nature appears throughout. Birds, flowers, and the moon are all symbols of the love theme, and every poem deals with some aspects of romance and its connection with human experience. In fact, with the Eichendorff Liederkreis, Schumann virtually invented a new type of song, the romantic night piece, serene, ecstatic, or ominous.

Schumann, of course, was a born melodist, and a few years earlier, he made an interesting comparison. He writes, “Chess and music are much alike. The queen (melody) has the most power, although the king (harmony) is always the decisive factor. As a scholar writes, “This witty comparison reveals a deep awareness of not only the strength of the melody’s influence, but also the knowledge of the diversity of possible ways of shaping the course of voices in a musical piece.”

Robert Schumann: “Melancholy” (arr. F. Meinders for piano) (Frederic Meinders, piano)

In a Distant Land

The Liederkreis opens with a setting of “In der Fremde” (In a Distant Land), typical in its expression of estrangement and nostalgia amid a dark, woodland landscape. Schumann’s tune has a haunting pathos, discreetly heightened by its gently rippling arpeggio accompaniment.

From my homeland beyond the red flashes,

That’s where the clouds come from,

But my father and mother are long dead,

And no one knows me there now.

How soon, oh, how soon the quiet time will come,

Then I will rest, too, and over me

Will murmur the lovely forest solitude,

And no one here will know me either.

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39, No. 1 “In a distant Land” (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

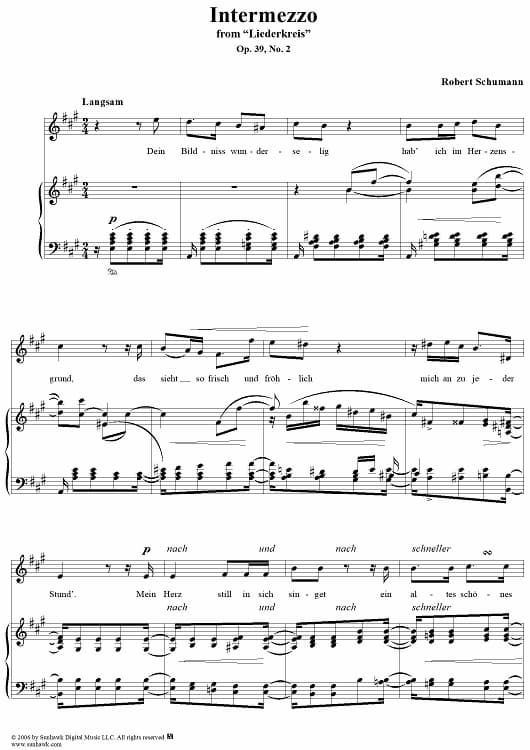

Intermezzo

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39 “Intermezzo”

“Intermezzo” No. 2 is an increasingly impassioned avowal of love to Clara, growing from a falling five-note figure Schumann often associated with her. It is a passionate love song featuring Schumann’s predilection for syncopation. The syncopated left hand, expressing delight in love is later joined by an independent melody echoing the words “you are like a flower.”

Your wondrous lovely image

I keep in the depths of my heart,

It gazes so fresh and cheerfully

At me always.

My heart sings to itself quietly

A familiar fair song,

That rises into the air

And flies quickly to you.

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39, No. 2 “Intermezzo” (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

Forest Conversation

The forest becomes most sinister in “Waldesgespräch” No. 3 (Forest Conversation). It is a variation of the Lorelei myth, with a hunter encountering an enchantress. Hunting horns accompany the meeting of the rider and the pale stranger, and she accosts him without warning. As the key abruptly changes, the enchantress tells him to flee while he admires her beauty. In a beautiful timed moment of recognition, and with the ironic echoing of the hunting horns, the piano quietly dies away in the postlude.

It’s already late, it’s already cold,

Why are you riding alone through the forest,

The forest is long, you are alone,

You lovely maid, I’ll see you home!

“The guile and trickery of men is vast,

My heart is broken by grief,

The hunting horn sounds here and there,

Oh flee! You don’t know who I am.”

So richly adorned are horse and woman,

So wondrous fair the young figure,

Now I know you—God help me!

You are the sorceress Lorelei.

“You know me well—from the high cliff

My castle looks silently deep into the Rhine.

It’s already late, it’s already cold,

You’ll never escape from this forest.”

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39, No. 3 “Forrest Conversation” (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

Stillness

After the dramatic forest conversation, “Die Stille” No. 4 (Stillness) provides a complete contrast. Secretive, confessional, and feminine, it begins without a prelude and unfolds as a delicate reverie in which the girl tells of her happiness.

No one knows or can guess

How good I feel, how good!

Oh, if only one knew it, just one,

No other person need know.

It’s not so quiet outside in the snow,

Nor so silent and secret

Are the stars in the sky

As my thoughts are.

I wish I were a little bird

And could fly over the sea

Right over the sea and further

Until I was in heaven!

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39, No. 4 “Stillness” (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

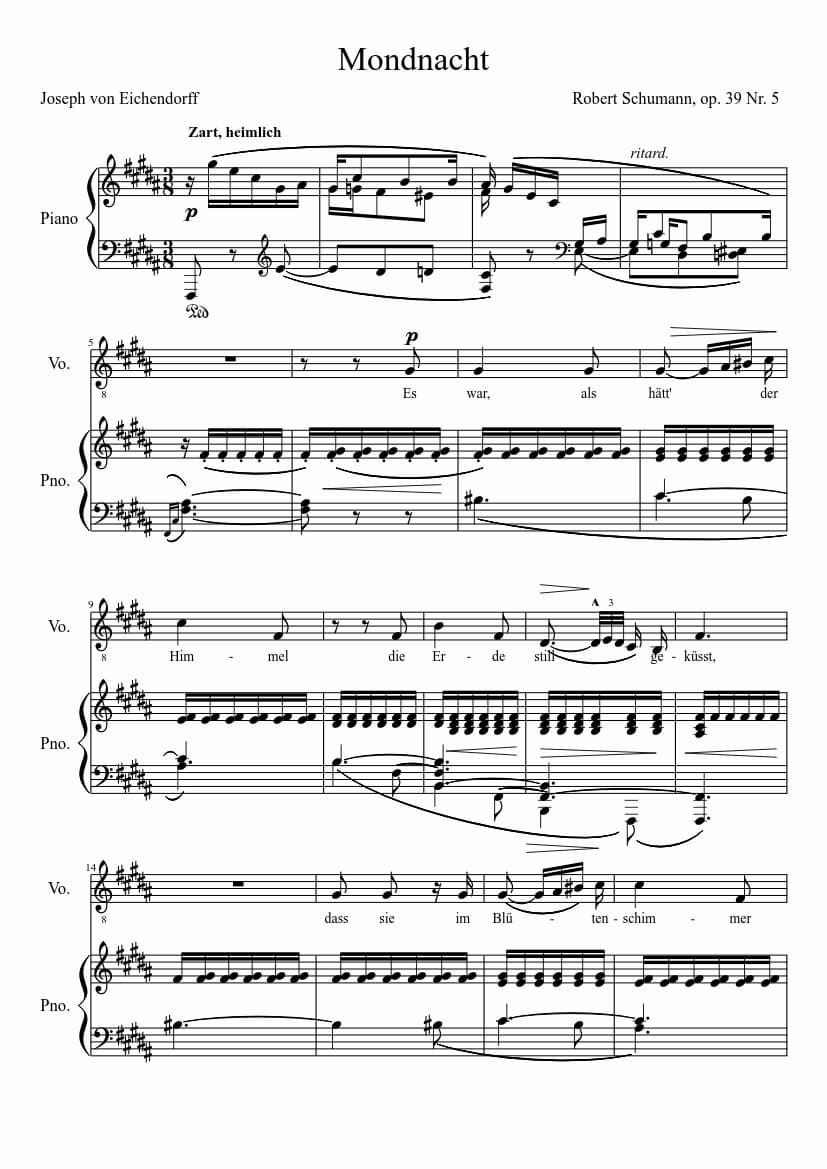

Moonlit Night

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39 “Moonlit Night”

Quite possibly the world’s loveliest vocal nocturne, “Mondnacht” No. 5 (Moonlit Night), is also the most famous song of the cycle. Here, Schumann matches the art of the poet in richness, nuance and form, creating a context in which verbal and musical elements embrace and reinforce one another. The human soul is yearning for a reunion with the universal soul of the divine in a search for a fleeting moment of bliss and fulfilment.

It was as if the sky

Had silently kissed the earth,

So that she, in the blossoms’ radiance,

Must now only dream of him.

The breeze passed through the fields,

The grain swayed gently

The woods murmured quietly,

The night was so starry clear.

And my soul spread

Its wings out widely,

Flew through the silent lands

As if it flew toward home.

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39, No. 5 “Moonlit Night”

Lovely Distant Land

“Schöne Fremde” No. 6 (Lovely Distant Land) is another night song, but instead of the hushed moonlit night, there is now a breeze blowing through the trees. Yet, it is still the mystery and magic of nature below the moon that shines at the core of the setting. The shimmering treble melodies are now broken up and there is clear movement in the bass.

The treetops rustle and tremble

As if at this hour

Around the half-sunken wall

The old gods danced.

Here behind the myrtle trees

In secret, twilit splendour,

Why do you speak wildly, as in dreams,

To me, fantastic night?

All the stars sparkle down on me

With the radiant glance of love,

The distant lands speak ecstatically

Of a future, great happiness.

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39, No. 6 “Lovely distant Land” (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

In a Fortress

“Auf einer Burg” No. 7 (In a Fortress) evokes the mysterious times of knighthood, with an old knight sitting alone in his castle for many hundred years before turning to stone. The setting is almost completely devoid of human emotion, with a gloomy, incantatory vocal line and modal harmonies. The melodic line consists of falling fifths and rising sixths, and even the pretty bride in the wedding party passing by, is weeping.

Fallen asleep on his watch

Up there is the old knight;

Rain showers pass by

And the forest murmurs through the bars.

Overgrown are beard and hair

Turned to stone are coat and collar,

He has been sitting many hundred years

Up there in his silent refuge.

Outside it’s quiet and peaceful,

Everyone has gone to the valley,

Forest birds sing solitary

In the empty window arches.

A bridal party rides down below

Upon the Rhine in sunshine,

Musicians play cheerfully

And the lovely bride weeps.

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39, No. 7 “In a Fortress” (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

In a Distant Land

“In der Fremde” No. 8 (In a Distant Land) is once again a song of exile. However, while the opening song had started with a brooding and profound utterance of loneliness and separateness, now the wind cannot be trusted. It speaks of other times and places, joyous unions and beloved people who are out of reach. Nature is not here to comfort or help the lonely soul but becomes a disorienting and disturbing force.

I hear the brooklets murmuring

Through the forest, here and there,

In the forest, in the murmuring

I do not know where I am.

Nightingales are singing

here in the solitude,

As though they wished to tell

Of lovely days now past.

The moonlight flickers,

As though I saw below me

The castle in the valley,

Yet it lies so far from here!

As though in the garden,

Full of roses, white and red,

My love were waiting for me,

Yet she died so long ago.

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39, No. 8 “In a distant Land” (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

Melancholy

Schumann wrote one of his most enchanting and beautiful melodies for “Wehmut” No. 9 (Melancholy). The words tell of a profound sense of resignation, but that sense of melancholy is only superficial. The melancholy is actually a happy one, as tears flow after hearing a joyful song.

I can still sing sometimes

As if I were happy,

But secretly tears well up

And I begin to weep.

Nightingales pour forth,

When spring breezes play outside,

Their echoing song of longing,

From the depths of their prisons.

Then all hearts listen,

And all are delighted,

But no one feels the pains,

The deep sorrow in the song.

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39, No. 9 “Melancholy” (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

Twilight

Friedrich Wieck

In “Zwielicht” No. 10 (Twilight), Schumann creates an oppressively sinister mood. Twilight falls, and with it, the coming of darkness treachery. The piano accompaniment coils around the voice in oppressive chromaticism, wanting to almost strangle the sense of tonal outlines. Possibly, Schumann remembered the time when Clara, torn between loyalty to her father and Schumann, abruptly discounted all ideas about marriage.

Darkness is spreading its wings,

The trees murmur ominously,

Clouds gather like oppressive dreams—

What does this dread mean?

If you have a favorite roe-deer,

Don’t let it graze alone,

Hunters ride in the forest and blow,

Sounding their horns and passing on.

If you have a friend on earth,

Don’t trust him at this hour,

Friendly perhaps in glance and voice,

He’s planning war in deceptive peace.

What perishes today in weariness,

will arise tomorrow newly born.

Things go astray in the night—

Be careful, stay alert and watchful!

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39, No. 10 “Twilight” (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

In the Forest

In the second-to-last song, “Im Walde” No. 11 (In the Forest), memories of the wedding party and the hunting horns are evoked by a lively rhythmic accompaniment. Suddenly, everything falls silent, and we are left with a sighing forest and the poet’s fear amid a darkening inner and outer landscape.

A wedding party passed along the mountain,

I heard the birds singing,

Many riders flashed, the forest horn sounded,

It was a merry hunt!

And before I knew it, everything was silent,

Night covered the horizon,

Only the forest still rustled on the mountains,

And I shuddered in the depths of my heart.

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39, No. 11 “In the Forest” (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

Spring Night

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39 “Spring Night”

The Liederkreis ends with “Frühlingsnacht” No. 12 (Spring Night). After the rather eerie forest song, we have arrived at an ecstatic conclusion. As the poet welcomes spring, the moon is shining, and all of nature is shouting, “She is yours, she is yours.” What a wonderful shimmering vision of physical and spiritual elation. The Op. 39 Liederkreis is probably the most refined and textually most faithful of Schuman’s vocal cycles, showcasing the typical ideal lyrical fusion of poem and song.

Over the garden in the air

I heard migrating birds passing,

That means spring is in the air

Below, it has already started to bloom.

I’d like to rejoice, I’d like to weep,

And it seems it couldn’t be true!

Old wonders appear again

Out in the moonlight.

And the moon, the stars say it,

And the grove murmurs it in dreams,

And the nightingales sing it:

She is yours, she is yours!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39, No. 12 “Spring Night” (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)