When we think of Richard Wagner, born on 22 May 1813, we envision grand operas, mythic tales, and orchestral splendour. Works like The Ring Cycle, Tristan and Isolde, or Lohengrin thrived in the theatre, where he could blend music, drama, poetry, and visuals into a “total work of art.” Wagner is synonymous with larger-than-life musical dramas that redefined opera and pushed the boundaries of musical expression.

Richard Wagner at the piano

Yet, tucked away in the shadow of his operatic masterpieces lies a small but fascinating body of work: his piano music. The piano was a more personal medium for Wagner, often serving as a tool for sketching ideas or exploring musical thoughts. His piano output is modest, consisting mainly of short pieces, an occasional sonata, transcriptions, arrangements, and pieces dedicated to friends, lovers, or patrons.

On the occasion of Wagner’s birthday on 22 May, let us briefly explore this lesser-known aspect of his compositional oeuvre.

Unpolished Keys

Richard Wagner

Richard Wagner: “Albumblatt in E Major” (Pier Paolo Vincenzi, piano)

One thing for sure, Richard Wagner was not a talented pianist. His first piano teacher bluntly told his young charge that nothing would ever come of him. Richard was furious, but later recalled, “Of course, the man was right…In all my life, I have never learned to play the piano properly. Thenceforth, I played for my own amusement; nothing but overtures with the most fearful fingering. It was impossible for me to play a passage clearly, and I conceived a great dread of all scales and runs.”

Wagner’s secret keys, however, do offer a unique window into his creative mind, revealing a more intimate and experimental side. For starters, the piano provides insight into Wagner’s creative process, as it was his primary tool for composing. He would often work out his operatic ideas at the keyboard, and the “Albumblatt in E Major” sounds Wagner in a raw and unfiltered state. It’s a musical prototype that could later be transformed into the grand tapestries of his operas.

Pianistic Ventures

Richard Wagner’s Piano Sonata Op. 1

Richard Wagner: Piano Sonata in B-flat Major, Op. 1 (Pier Paolo Vincenzi, piano)

While Wagner is best remembered for his operas, his ability to write for the piano demonstrates that he was not a one-dimensional composer. It certainly highlights his musical versatility, even if his theatrical instincts shine through. His B-flat Major sonata sounds his engagement with the Classical tradition, underscoring his deep connection to the musical culture of the time.

The Wagner catalogue of works mentions two sonatas for solo piano and one sonata for four hands, but all three of these early efforts have been lost. Op. 1 was published in 1831, and critics suggest that “in the context of Wagner’s wider piano output, it is a somewhat naïve and redundant work.” However, it might be considered fundamental evidence of Wagner’s education under Christian Theodor Weinlig, cantor of St. Thomas in Leipzig.

Beethoven’s Shadow

Richard Wagner: Piano Sonata in A Major, Op. 4 “Grosse Sonate” (Pier Paolo Vincenzi, piano)

Once Richard Wagner had decided to take proper lessons with Theodor Weinlig, he violently rebelled against exercises in counterpoint and canon. Nevertheless, by relying on the legacy of Beethoven and the pianism of Ignaz Pleyel and Carl Maria von Weber, Wagner produced his most complex piano works in the Sonata in A, Op. 4. He even considered creating a symphonic version of this sonata, but abandoned that idea in 1834.

Originally Wagner cast the work in four movements, but in the end eliminated the fugue movement. From the opening theme, the shadow of Ludwig van Beethoven is everywhere. The slow movement offers two captivating melodies, and the Finale is a high-spirited affair in the manner of Carl Maria von Weber. The work was published only in 1960, and Wagner would later distance himself from his early compositions by declaring them “mere plagiarisms from my youth.”

Wesendonck Sonata

Minna Wagner

Richard Wagner: Eine Sonate für das Album von Frau Mathtilde Wesendonck (Pier Paolo Vincenzi, piano)

It would take Richard Wagner 21 years before he tackled a piano sonata again. The single-movement work often referred to as the “Wesendonck Sonata” is a highly personal response to his relationship with Mathilde, the wife of his patron Otto Wesendonck. Richard developed a close intellectual and emotional relationship with Mathilde while staying at the family residence in Zurich for over ten years. He certainly was consumed by an ever-growing passion for Mathilde.

The sonata foreshadows the harmonic complexity of Tristan, as transitions between themes often feature unexpected modulations. It certainly is a highly intimate and passionate work with a sense of personal expression that aligns with his feelings for Mathilde. The mood oscillates between ardent lyricism and tender reflection. Wager described it as a minor work in his correspondence, surely deflecting attention from its personal significance.

Passionate Ode

Richard Wagner: “Notenbrief für Mathilde Wesendonck” (Pier Paolo Vincenzi, piano)

Wagner’s “Notenbrief für Mathilde” is a direct reflection of the composer’s bond with Mathilde Wesendonck, whose poetry and presence shaped his creative output in the late 1850s. Its intimate tone and title suggest a private dialogue, which reveals Wagner’s deep admiration and emotional dependence on her.

The subtle chromatic inflections create a sense of longing, while the cantabile melody reflects Wagner’s operatic sensibility. This vocal influence aligns with the Wesendonck Lieder, Wagner’s setting of Mathilde’s poems. As a “musical letter”, the piece carries symbolic weight, serving as a musical equivalent of Wagner’s written correspondence. In Wagner’s oeuvre, the choice of E-flat Major is generally associated with warmth and nobility, reinforcing this personal significance.

Tristan Echoes

Mathilde Wesendonck

Richard Wagner: Tristan and Isolde, “Vorspiel und Schluss” (Pier Paolo Vincenzi, piano)

As pianist Pier Paolo Vincenzi writes, “among Wagner’s correspondence with Mathilde Wesendonck there is, attached to a letter of 1859, a small extract from what is a pillar of German Romanticism and, at the same time, a turning point and a bridge towards the evolution of the musical language of the 20th century: Tristan und Isolde.” By that time, things had gotten a bit more complicated as Minna Wagner had intercepted a letter from Richard to Mathilde.

Wagner had written, “The day before yesterday, an angel came to me at noon, blessed and comforted me. Now I am able to pray to my angel with heartfelt emotion. This prayer is a prayer of love. Love! Profound joy in this love, it is the source of my salvation. When I look into your eyes, there is nothing more to say. I feel so sure of myself when this wonderful, sacred gaze falls upon me and envelops me…” Otto Wesendonck terminated Wagner’s Zurich residency, but the composer continued to write lavish “fantasy love letters” to Mathilde nevertheless.

Musical Keepsakes

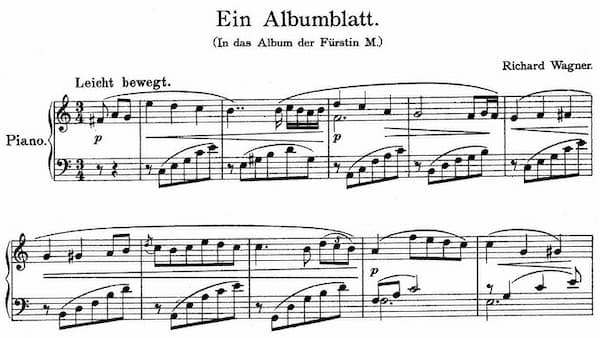

Wagner: Albumblatt in C Major, “In das Album der Fürstin Metternich”

Richard Wagner: Albumblatt in C Major, “In das Album der Fürstin Metternich” (Pier Paolo Vincenzi, piano)

The “Albumblatt” was a fashionable genre in the 19th century. It was a brief and expressive piece often inscribed in an album as a musical keepsake, akin to a signed photograph or a personal note. For Wagner, these pieces served as tokens of gratitude or affection, often written for patrons who supported him financially or socially.

One such “Albumblatt” is dedicated to the Princess Pauline Metternich, an Austrian noblewoman and influential figure in European cultural circles. A key patron of Wagner, she helped secure the 1861 premiere of Tannhäuser in Paris. The “Albumblatt” dates from 1862 and was likely a token of gratitude for her advocacy.

Intimate Art

Richard Wagner: Albumblatt in A-flat Major, “Ankunft bei den schwarzen Schwänen” (Pier Paolo Vincenzi, piano)

The Albumblatt in A-flat Major also dates from Wagner’s time in Paris. It is dedicated to Countess Marie de Pourtalès, a prominent figure in Parisian high society. The wife of Count Edmond de Pourtalès, a wealthy banker and art collector, she hosted a prominent salon for artists, musicians, and intellectuals.

The inscription “Arrival at the Black Swans” seemingly refers to Wagner’s troubles surrounding the Tannhäuser premiere in 1861. This Albumblatt bears traces of Wagner’s operatic vocabulary, particularly in its lyrical melody and chromatic touches. It certainly underscores the importance of patronage in Wagner’s career and his reliance on personal relationships to sustain his artistic vision.

Richard Wagner’s piano music offers an intimate counterpoint to the monumental scale of his operatic creations. They reveal a composer capable of distilling his harmonic innovation and lyrical expressiveness into concise and personal forms. More than mere ephemera, Wagner’s piano music invites reconsideration as a vital and valuable insight into his broader cultural milieu and creative process.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Richard Wagner: Fantasia in F-sharp minor (Pier Paolo Vincenzi, piano)