Music is a wonderful support for sensorial illustrations and evocative descriptions. While some is considered absolute — music for the sake of music — the contrast, expressive music, is often a great support for composers’ creativity.

© Kathy Collins / Getty Images

Also known as program music, it has been written in Western Europe for many centuries, starting around the Renaissance and up to today’s soundtracks and popular music. Defined by the attempt to render an extra-musical narrative, it is mostly attributed to instrumental music and often accompanied with program notes.

Although mostly unlimited in the themes and approaches, there seems to be a recurrent idea or main subject that comes back over and over again: nature. Through the evocation of birds and animals, the illustration of rain and thunder or the sound of the waves, nature seems to be an infinite source of inspiration for composers.

Antonio Vivaldi/Max Richter

One of the most famous set of concerti ever written — and certainly one of the most well-known baroque musical work; Vivaldi’s Four Seasons is an ensemble of concerti for violin and orchestra, composed around 1721, and very often considered as the pinnacle of descriptive music, and a revolution in musical conception.

The evocative music takes turns with each season in describing singing birds, storms, hunting parties or frozen landscapes, through innovative strings writing and orchestral arrangements.

From such an influential work, in 2012 the British composer Max Richter released Recomposed by Max Richter: Vivaldi – The Four Seasons, a rework of the original concerti with Richter’s minimalistic approach.

Ludwig van Beethoven

© Allergic Living Canada

From its starting point, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 in F major, Op. 68 — also known as the Pastoral Symphony — recalls nature and its attributes. Composed in 1808, it contains five movements each associated with a programmatic title, such as “Scene by the brook” or “Thunder, Storm”.

Beethoven depicts rural landscapes and sensations, and has clear references to nature’s qualities such as bird calls, or thunderstorm and rain. He makes extensive use of rhythmic cells to convey the repetition of patterns in nature, as well as an altered version of the usual sonata rondo form for scherzi to describe rural dances and atmospheres.

The Pastoral Symphony is not the only work in which Beethoven pays homage to nature, his Violin Sonata No. 5 in F Major, Op. 24 — Spring — or Piano Sonata No. 17 in D Minor, Op. 31— Tempest —is another good set of examples of his most descriptive music.

Claude Debussy

© SurferToday.com

La Mer, also known as La Mer, trois esquisses symphoniques pour orchestra, was composed by Debussy in 1905. Although not during his time, it is now one of his most admired work and a very good example of his compositional style.

Described by the composer as sketches for orchestra — through the use of impressionistic harmonies, impressive tonal colours, descriptive musical devices and innovative orchestral writing — the work is structured around three movements, growing in excitement and motion. Although not considered by many as being program music as it stands—some suggest the work being a hidden symphony — I truly believe that La Mer represents a beautiful example of how evocative and descriptive Debussy’s music is.

Being an isolated example, I cannot recommend enough the discovery of his works — in particular his Préludes or Images — as they constitute on their own a masterpiece in expressive music.

Debussy: La mer (Philharmonia Orchestra; Pablo Heras-Casado, cond.)

Olivier Messiaen

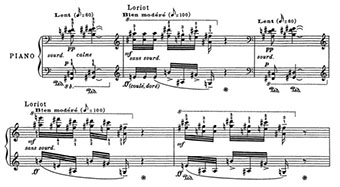

Messiaen’s Catalogue d’oiseaux, imitating the song of Golden Oriole

© Stretta Music

Catalogues d’oiseaux, I/42 is a collection of thirteen pieces for piano solo by Messiaen, completed in 1958. A work devoted to birds, it is the result of his passion for their songs, which he recorded, transcribed and catalogued methodically. The work does not limit itself only to birds, as it also refers to a selection of French provinces; their habitat, rural landscape and scenery.

The work impresses listeners by its authenticity with nature, and is somehow a stretch from traditional perception of musicality, a characteristic of Messiaen’s compositional style. Perhaps a bit unusual for the untrained ear, it is however very easy to picture birds, and to hear them sing naturally through each piece.

Catalogue d’oiseaux is not Messiaen’s only work that centers on birdsongs and natural pictures, and another great set of examples is Réveil d’oiseaux or Petites esquisses d’oiseaux.

Messiaen: Catalogue d’oiseaux (Catalogue of Birds) – No. 2. Le Loriot (Golden Oriole) (Pierre-Laurent Aimard, piano)

Messiaen: Catalogue d’oiseaux (Catalogue of Birds) – No. 3. Le Merle bleu (Blue Rock Thrush) (Pierre-Laurent Aimard, piano)

Messiaen: Catalogue d’oiseaux (Catalogue of Birds) – No. 8. L’Alouette Calandrelle (Short-toed Lark) (Pierre-Laurent Aimard, piano)

Messiaen: Catalogue d’oiseaux (Catalogue of Birds) – No. 11. La Buse variable (Buzzard) (Pierre-Laurent Aimard, piano)

Philip Glass

An American composer who attempted to describe nature and the seasons is Glass — known for being one of the fathers of minimalism, with The American Four Seasons, his Violin Concerto No. 2, premiered in 2009.

Although treating the same subject as Vivaldi, Glass’ take is very different; in his point of view The American Four Seasons are a companion to Vivaldi’s. The concerto is structured very oddly, alternating between movements and introductive preludes and songs. The particularity of these sets of pieces is that no indication has been provided on which movement relates to which season: it is the listener’s role to make his own interpretation.

This freedom allows the listener’s experience of the natural seasons to interfere with the composer’s initial direction. Glass’ concerto is a lot less precise and detailed in its description of nature’s elements than Vivaldi’s, leaving more space for creativity and interpretation for the listener.

Through each one of these works, it has been observed how abundant nature is when it comes to inspiring composers. Similarly to painters, they take inspiration in every detail of their environment, from the fauna to the flora or the seasons to the sea.

While I have focused this article on just a few pieces, there are countless works of art that would have been worth mentioning, such as Biber’s Sonata Representativa, Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons, Ravel’s Jeux d’eau, Vaughan Williams’ Sinfonia Antartica or Urmas’ Starry Sky Cycle.

Nature keeps inspiring composers and artists perhaps because of its infinity and endless diversity; inspiration seems to be triggered seamlessly, and one only needs to open his eyes and ears and enjoy the scenery surrounding him for the music to start flowing.

What’s this, no Sibelius?

Touché !

The Lark Ascending?