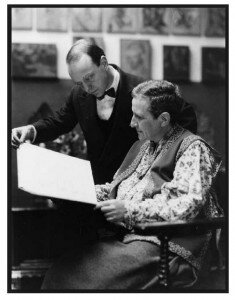

Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein

In 1926, the American composer Virgil Thomson went to the fabled address of 27 Rue de Fleurus, where the American poet and writer Gertrude Stein lived with her companion, Alice B. Toklas. Thomson was familiar with Stein’s writings and spoke about them with insight. Stein decided to keep Thomson in her circle and by early 1927, he delivered to her his first setting of one of her texts, Susie Asado.

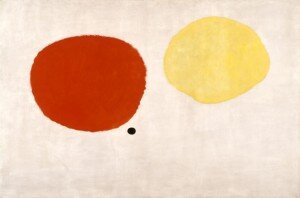

Miró: Painting (1930)

Stein’s famously repetitive text style (Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose), where meaning changes with repetition, suited Thomson’s theories of setting English-language text to music, and he said:

“My hope in putting Gertrude Stein to music has been to break, crack open, and solve for all time anything still waiting to be solved, which was almost everything, about English Musical declamation. My theory was that if a text is set correctly for the sound of it, then the meaning would take care of itself. … With meanings already abstracted, or absent, or so multiplied that choice among them was impossible, there was no temptation toward tonal illustration, say, of birdie babbling by the brook or heavy heavy hangs the heart. You could make a setting for sound and syntax only, then add, if needed, an accompaniment equally functional.”

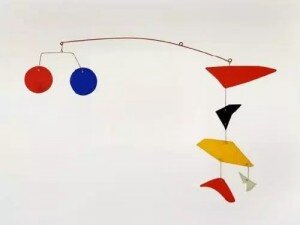

Calder: Enseign de Lunettes

In Susie Asado, Thomson used the simple building blocks of music: arpeggios and scales, which he later compared to ‘the squares, circles and discs found regularly in the paintings of Joan Mirò and the sculptures of Alexander Calder.’ Calder and other contemporaries, such as Mondrian, also worked in simple primary colours, just as Thomson was doing with music

In setting aside the romance of poetry, Stein and then Thomson concentrated on the rhythm of the words themselves as driving the music. They looked for a project and came up with the idea of an opera with the subject of Spanish saints.

Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas,27 rue de Fleurus (handcoloured)

The text Stein delivered was described as ‘meandering and plotless with no scenes or discernible action.’ The subject of Four Saints in Three Acts were Spanish 16th century saints: St. Teresa, St. Ignatius, St. Settlement, and St. Chavez. An additional 15 saints form the Chorus. The text includes discussions about what was happening in the Stein household, injections of religious imagery (fish, for example), and Thomson set every word of it, even the stage directions. Innovations that Thomson added were dividing the principle saint’s role into St. Teresa I (soprano) and St. Teresa II (contralto) so she could sing duets with herself. Thomson chose an all-black cast for the premiere, but did not constrain future productions to that choice.

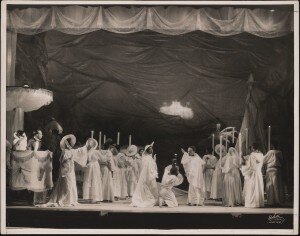

Looking at the Heavenly Mansion, 4 Saints in 3 Acts (White, 1934)

To get the work on stage, Thomson called on his friend, the painter Maurice Grosser, another avid reader of Stein, and he created the book, or the scenario for the work, mediating between the words and the music. For example, when Stein has the text ‘How many windows and doors and floors are there in it,’ Grosser took it to be an allusion to a Vision of a Heavenly Mansion and had one of the chorus saints enter with a telescope to see the celestial mansion. Other parts of the book were created around single words, and others, sometimes, had to be created out of the air.

Thomson in rehearsal with the cast

Grosser was a landscape painter and portraitist and his idea of the book/scenario for the opera was that it was a set of paintings. Images of religious art from across the centuries informed Grosser’s imagination. Historically, St. Teresa was a saint of religious ecstasy and visions and St. Ignatius was a militant saint, but in the opera, those fierce characters have been worn down through time.

As we listen to the start of Act III, we can hear Thomson’s very American-sounding simple harmonies and yet tipped with a few Spanish sounds at the same time. Some accordions come in and the overall feeling is less Renaissance Spain than, perhaps, Missouri.

Lee Miller: Edward Matthews as St. Ignatius (1933)

A review of a 2013 performance of the work in Boston talked about the repetitions in Stein’s text worked well with the American folk and gospel styles used by Thomson (we hear similar harmonies in Copland). The reviewer also points out that an opera such as Philip Glass and Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach (1976) isn’t that different from this opera of 50 years earlier. Is Stein’s text style of the Prologue, with its lists, that different from the incessant counting of the Knee 1 section?

Glass: Einstein on the Beach: Knee 1 (Philip Glass Ensemble; Michael Riesman, cond.)

To get through Stein’s texts, a clear diction is required of the singers, more in keeping with the hymn and gospel styles that Thomson references, because, in the end, it’s the text that’s important.

And if we look at a very modern opera, Mason Bates‘ The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs (2017), we can still hear those elements of Stein and Thomson: clear diction, and perhaps even, considering the subject and what the object has become, the same nonsensical text:

The modernist opera created by Virgil Thomson continues to resonate to this day.