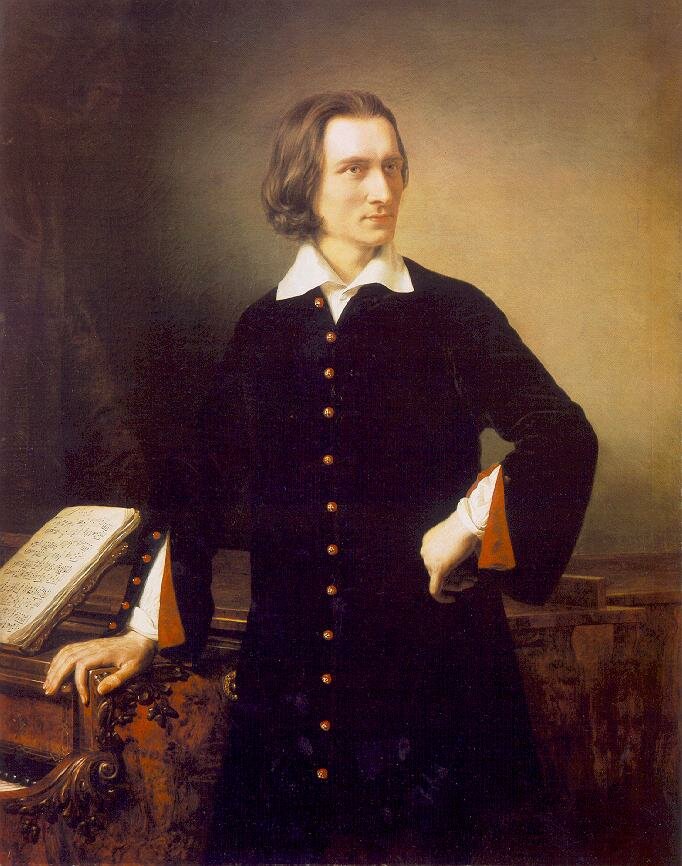

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s original Anton-Walter-piano pictured at Mozart’s former apartment in central Vienna (REUTERS/Herwig Prammer)

Say “Piano Sonata” and most people will think of Beethoven’s ‘Moonlight’ Sonata (Op. 27/2), a work which bears what is generally considered to be the standard structure of a sonata – a work in three movements, usually with a slow middle movement and a fast-paced finale (in fact, the Moonlight sonata does not adhere to this organisation). While composers have sought to adapt the genre (adding movements or scoring the work in a single ‘fantasy’ movement), this standard three-movement template has remained the bedrock of the sonata’s structure for over three hundred years.

The evolution of the piano sonata is interesting not only for the progression of a distinct musical form but also because it charts the development and improvement in piano design, from the instrument’s invention in the early eighteenth century to the introduction of the cast-iron frame in the 1820s.

The word “sonata” comes from the Latin and Italian: sonare, “to sound”, and literally means music that was played rather than sung. The earliest keyboard sonatas, from the Baroque era, were mostly short, one-movement works. Domenico Scarlatti wrote over 500 such ‘sonatas’ in one-movement structure, in which the seed of the standard sonata’s form was set. Usually scored in ternary (ABA) form, these miniatures predict the standard three-movement format of the Classical sonata. Bach wrote a number of concertos for solo keyboard. Also in three movements, with a lyrical middle movement and a lively rondo finale, these are sonatas in all but name.

By the late eighteenth century the piano sonata was established in the format we know it today – an Allegro (brisk) first movement, a slow movement (Adagio, Andante or Largo, or a minuet and trio) and a fast finale, usually scored in rondo form.

The piano sonatas of both Haydn and Mozart chart the decline of the harpsichord and clavichord and the rapid development of the piano, both in terms of its technology and extended expressive capabilities.

Haydn: Keyboard Sonata No. 62 in E-Flat Major, Hob.XVI:52

The early sonatas of Haydn and Mozart point to an instrument with a limited range of around 5 octaves (compare this with the modern piano whose range is almost 8 octaves), yet within these confines both composers wrote remarkably fine works for the instrument. Of Haydn’s 60-odd piano sonatas, his three great late sonatas in particular show him responding to the greater sonority offered by John Broadwood & Son’s pianos, instruments which Haydn encountered during his visits to London. The opening of the E-flat major sonata Hob. XVI: 52 has a symphonic grandeur, offset by glittering passagework and sprightly dotted figures. The slow movement is one of infinite elegance and operative lyricism, while the toccata-like Finale really tests the technology of the Broadwood’s more nimble action. Earlier, in the C major sonata, Hob. XVI: 50, Haydn makes innovative use of the pedal in the slow movement – not the sustaining (right hand) pedal but rather the ‘open’ or una corda pedal, available on the new Broadwood instrument, to create a passage of ethereal mystery.

Haydn: Keyboard Sonata No. 60 in C Major, Hob.XVI:50 – II. Adagio

Mozart also appreciated the scope of the new instrument and the sparkling variety of his piano sonatas reflect the “ideal sound” these new instruments afforded. The ‘Pianoforte’, as its name suggests, could play both soft and loud, and in his sensitivity to different vocal and orchestral timbres, Mozart implied particular instruments through the use of contrasting voicing, dramatic dynamic chiaroscuro, registers and textures, and his vibrant musical imagination. We find orchestral tutti, operatic arias and recitative, string quartet idioms, tender woodwind exchanges, brass fanfares, all within the compass of a single instrument.

Mozart: Piano Sonata No. 5 in G Major, K. 283