The clarinet concerto by Edison Denisov (1929-1996), premiered on 9 July 1989, finds the European-oriented composer firmly rooted in Russian-Siberian soil, “developing a certain partiality to the tonal qualities of the clarinet.” In fact, the clarinet had previously featured in a number of Denisov compositions. His 1968 “Ode for clarinet, piano and percussion” sounds an edgy synthesis of Darmstadt modernism, and the “Clarinet Sonata” of 1972 established itself as one of the seminal works of the clarinet repertory. “It was one of the first pieces by a Soviet avant-garde composer to be at all widely performed and with its micro-intervals, use of glissandi and other innovative techniques it showed the clarinet in an entirely new light.”

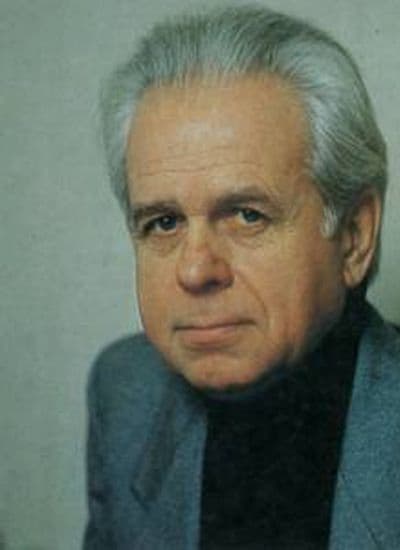

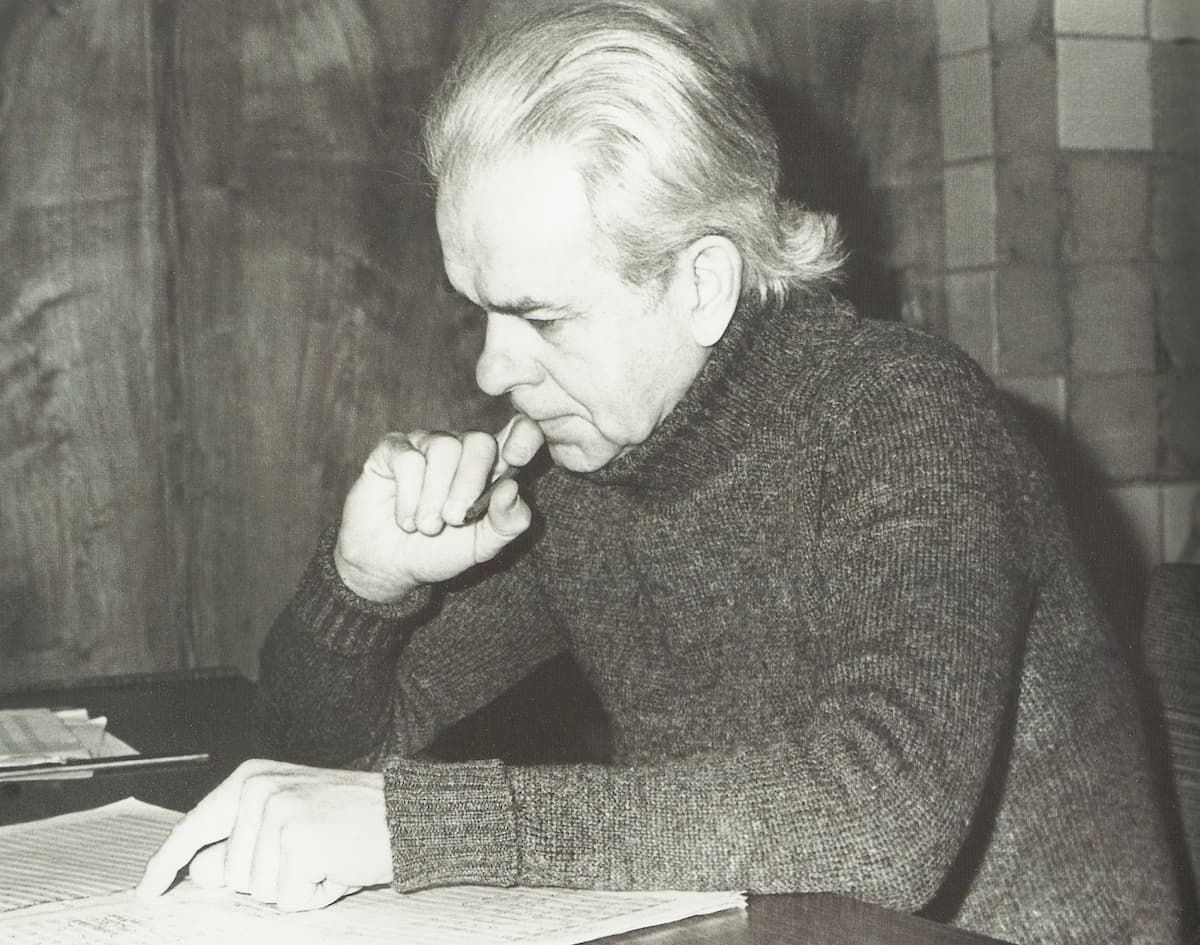

Edison Denisov

In his Clarinet Quintet of 1987, Denison was guided by “beauty as the principal factor in his work. This means not only beautiful sound, which, naturally, has nothing to do with outward prettiness, but beauty here means beautiful ideas as understood by mathematicians, or by Bach and Webern. The most important element of my music is its lyricism. I find serial procedures very promising, but in my work, I strive for synthesis and use tonality, modality, aleatory, and other expressive media.” Composed in the tradition of the classic-romantic clarinet quintets by Mozart, Weber, and Brahms, “the work places the clarinet at the starting point of the musical discourse. The compositional concentration increases as the movements proceed, “becoming tighter and tighter towards the finale.”

Edison Denisov: Sonata for clarinet solo

Named after the American inventor Thomas Edison, Denisov grew up in the town of Tomsk, frequently called the “Siberian Athens.” He studied mathematics, physics, and chemistry, and learned to play the mandolin, guitar, clarinet, and piano. He sent some of his earliest compositions to Shostakovich, who encouraged further studies at the Moscow Conservatory. As Shostakovich wrote, “Dear Edik, your compositions have astonished me… I believe that you are endowed with a great gift for composition and that it would be a great sin to bury your talent. Of course, to become a composer, you have a lot to learn.”

Kuznetsova Street 30, Tomsk, birthplace of Edison Denisov

Denisov eventually did enroll at the Moscow Conservatoire, and he was forced into the doctrine established by Joseph Stalin. “Good Socialist Realist artists,” a scholar explained, “were to depict the world as it was seen your party consciousness, with a view to the glorious future.” For composers, that meant that their music had to be “optimistic, aspiring to heroic exhilaration, and meeting the requirements of accessibility, tunefulness, stylistic traditionalism, and folk-inspired qualities.”

Some professors were more sympathetic to new music, and Denisov’s composition teacher Vissarion Shebalin was looking to educate his students using the widest scope of music possible. And that included forbidden music by Stravinsky, Hindemith, Schoenberg, Berg, Honegger, Dallapiccola, and Petrassi. Denisov received his degree in 1956, and upon completion of graduate studies, he embarked on an independent study of composers whose music he felt warranted his attention. His research and analysis led to a series of articles. In 1963, he was the first person in the field of Russian musicology to write a work on dodecaphony and serial technique.

Denisov came soon under pressure and was banned from teaching composition. As an administrator proclaimed, “In a year or two Denisov will dry up as a composer and therefore he has to be prepared for teaching theoretical subjects.” He was accused of painting a distorted picture of the state of Soviet music and dismissed from his teaching position at the Moscow Conservatoire altogether in 1967. His works were banned, and he was blacklisted “for unapproved participation in a number of festivals of Soviet music in the West.” Denisov eventually became a leader of the Association for Contemporary Music reestablished in Moscow in 1990.

The Clarinet Concerto expresses particularly strong symphonic inclinations. Full of extended lyricism, “several voices flower on par at different times in quasi-a-rhythmical and a-metrical rendering.” At this stage in his career, Denisov had refined his personal style, and beautifully engaged his fascination with tone colors and timbres. As a critic writes, “The rhapsodic first movement of the concerto is followed by a slow movement of great tonal beauty, a veritable lyrical swansong: grand, deeply moving music.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter