Claudio Arrau was probably the least flamboyant of pianists, avoiding virtuosic display as rigorously as some other pianists crave it. To be sure, he had the technical abilities of a virtuoso, but he was an intellectual and deeply reflective interpreter. According to Daniel Barenboim, “Arrau created a special sound known for its full-bodied and orchestral properties, and secondly, he produced a spellbound utterly disembodied timbre.”

Claudio Arrau Performs Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 3 in C Major, Op. 2, No. 3

Ancestry

Claudio Arrau was born on 6 February 1903 in Chillán, the capital city of the Ñuble Region in the Diguillín Province of Chile, located about 400 km south of the country’s capital, Santiago. His father’s family originally came from Provence, and Carlos Arrau was an ophthalmologist who died in a horseback riding accident when Claudio was one year old.

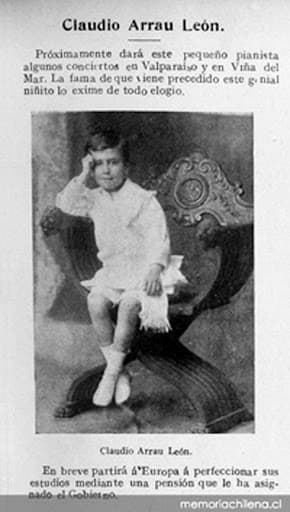

Claudio Arrau as a little boy

His mother, Lucrecia León Bravo de Villalba, had Spanish background, partly Andalusian and partly Castilian. Apparently, Lucrecia was trapped in an unhappy marriage as her husband supposedly had a habit of fathering a good many illegitimate children. She was an amateur pianist and lived, according to Claudio, “only from the moment they discovered my talent.”

Frédéric Chopin: Scherzo No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 31 (Claudio Arrau, piano)

The Talent

Arrau was a child prodigy who could read music before he could read words. His mother remembers that he taught himself to read music. “Claudio didn’t play with the other children, he stayed at my side and listened to me play the piano or finger the notes. When he was three, he sketched out lines, clefs, and notes.” There had never been a professional musician in his family, but his mother introduced him to the instrument.

Arrau loved Bach and was reading Beethoven‘s sonatas at the age of 4, and his first public recital took play in 1908. Arrau remembers a program that included pieces by Mozart, Beethoven, and Schumann. He might also have played a bit of Liszt, but as a contemporary critic writes, “The ecstatic audience showered him with applause until he returned to play a four-hand piece with his mother…If his love of the art endures, he is sure to become a musical sensation.”

Claudio Arrau Performs Schumann’s Carnaval Op. 9

The Scholarship

In October 1909, Arrau once again gave a full-fledged recital. He was called “the hero of the evening, and his performance was incredible; it was clearly the work of artistic genius, of one who is destined to see his name crowned in glory.” Arrau remembers playing for the members of the Chilean legislature, including the Chilean President Pedro Montt. Everybody quickly agreed that it was essential to secure a scholarship for the young genius.

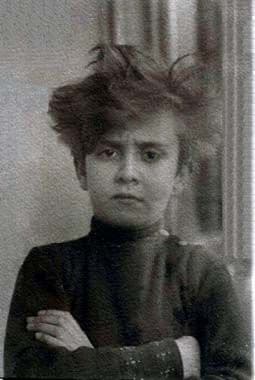

Young Claudio Arrau

In 1911, Arrau left home on a ten-year grant from the Chilean government to study in Germany. Accompanied by his mother, brother, and sister, he started his studies with Martin Krause in 1913. Krause had been a Liszt student and was known as one of Germany’s foremost pedagogues and critics. Although Arrau was underage, Krause arranged for him to enroll at the Stern Conservatory in Berlin. In his letter of recommendation, he writes, “Claudio Arrau, a highly endowed Chilean youth, has under my direction made the most astounding advances in piano playing…He is engrossed with his whole soul and enthusiasm in his art.”

Claudio Arrau Performs Brahms’ Piano Sonata No. 3 in F minor, Op. 5

Studies with Krause

Arrau was a shy boy and “had an inferiority complex. I thought I was still too undeveloped to play for such a famous man.” However, he remembers Krause as a nice man, a mixture of kindness and severity. Krause did not enjoy teaching child prodigies, but he knew that Arrau was special. As Krause wrote to a colleague in Leipzig, “In my opinion, Arrau is the greatest piano talent since Liszt.”

Claudio Arrau with Martin Krause, ca. 1914

Arrau took up lodgings in the Krause household, and he received a lesson every evening, “every day, an hour and a half at least.” Arrau remembers that Krause believed in practicing difficult passages at different speeds, in different rhythms, and in different keys. And then staccato, leggiero, martellato—all sorts of combinations. “You shouldn’t perform a work in public,” he would say, “unless you were able to play it ten times as fast and ten times as loud. You only communicate the feeling of mastery to an audience if you have tremendous reserves of technique.”

Krause died in the fifth year of teaching Arrau; he did not continue formal study after that point.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter