Born in Helsinki, Finland on 10 June 1958 to a businessman father and a homemaker mother, Esa-Pekka Salonen knew from an early age that music was his destiny. His mother tried to get him to play the piano at four, but he refused. “At that age,” he explains, “it was very clear to me that girls play piano and boys play soccer.” He took up the French horn with the initial aim of eventually joining an orchestra, but hearing Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony and Messiaen’s Turangalila made him want to become a composer.

Esa-Pekka Salonen

Having graduated from high school, Salonen enrolled at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki to study horn and composition. In no time, he “was fully immersed in the then-current rhetoric of European compositional ideology.” While many Finnish composers were still writing brooding symphonies in the spirit of Sibelius, a small but vocal group of advant-gardists were making their voices heard. As Alex Ross reports, “Salonen wrote a paper entitled “the defeat of tonalism,” and he once interrupted a school party by playing music by Pierre Boulez.

Esa-Pekka Salonen Conducts Debussy’s La Mer

With fellow students Magnus Lindberg and Kaija Saariaho, Salonen formed a music appreciation gang called “Korvat Auki!” (Ears Open). They started to put on new music for people, and one legendary evening was devoted to the conceptual composer Mauricio Kagel. “The audience consisted of two elderly ladies who had come by mistake; another attracted a janitor, his dog, and the mother of one of the composers.” They also formed a performance ensemble called “Toimii” (It Works).

These ensembles functioned as both performance groups and workshops, where ideas and compositions were created, critiqued, and polished on a scale not previously known in Finland. And it was within this performance group that Salonen started to study conducting. Salonen explains, “we felt that no real conductors would be interested in our music, so our association needed a conductor. I had maybe the most experience of performing music because I was a French horn player and I played in the Helsinki orchestras as a sub. So I became the conductor of the group.”

Esa-Pekka Salonen: Nachtlieder (David Howard, clarinet; Vicki Ray, piano)

Salonen remembers, “My friend played the violin, and another played piano, percussion, and I conducted because somebody had to do it. I grew up in an environment where conducting was just one activity among other musical activities. No better, no worse. I, not for a second, thought of myself as being more important than, say, a friend who played the viola or the flute. It was just a different function. I’m deeply grateful for that experience because it has helped me later in life in terms of how I communicate with musicians because my function is to keep things going. Not dictate, but enable, give them tools to achieve a certain result.”

Jorma Panula

During his years at the Sibelius Academy, Salonen nurtured and refined his talents as a composer, “emerging with a strong compositional voice steeped in avant-garde ideals.” In addition, he also became a talented conductor studying under Jorma Panula. Panula is one the most respected names in conducting pedagogy, a conductor who is happy to proclaim that he has no method.

Salonen Conducts Sibelius: “Death of Melisande”

Panula was quoted as saying that he “taught Salonen not only music, but also to read novels, appreciate art, and drink wine.” Panula was encouraging a well-rounded approach to life itself as well as to music-making. Salonen remembers that this open-mindedness and multi-faceted approach to conducting, composing, and life was greatly encouraged by his teacher. As he once wrote, “Everyone is doing everything.”

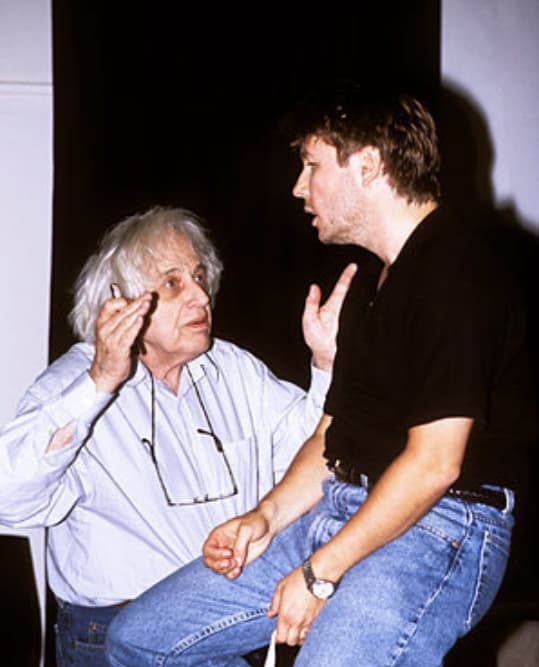

György Ligeti and Esa-Pekka Salonen

Having completed his composition studies, Salonen stood in front of the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra for the first time in 1979. However, his international career took off in 1983, when he stepped onto the podium on short notice to stand in for the indisposed Michael Tilson Thomas. On that evening, the London Philharmonic Orchestra performed Mahler’s third symphony, yet Salonen still considered himself more a composer than a conductor. This career-defining evening did not strike him initially as anything more than an opportunity. “It wasn’t a make-or-break thing for me,” he said. “I wanted to do my best, but I wasn’t planning on a conducting career.” The very next morning, however, “the phone and fax went wild.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

I just happened to be in London on that fateful day in 1983, and I attended that Mahler 3rd performance. The kid (he looked like an early adolescent) was simply outstanding, and the great work unfolded masterfully in his hands. Backstage afterwards congregated all the top honchos of the international music business – there was no question that we had just witnessed the birth of a major star!