Some say that Francis Poulenc was granted an ideal death. He died of a heart attack in his Paris apartment on the rue des Medicis, on 30 January 1963. On that day he was planning to have lunch with Denise Duval and record some additional radio broadcasts with his friend Stéphane Audel. Because he was nursing a bad cold, he canceled lunch and had his sudden heart attack at 1 p.m.

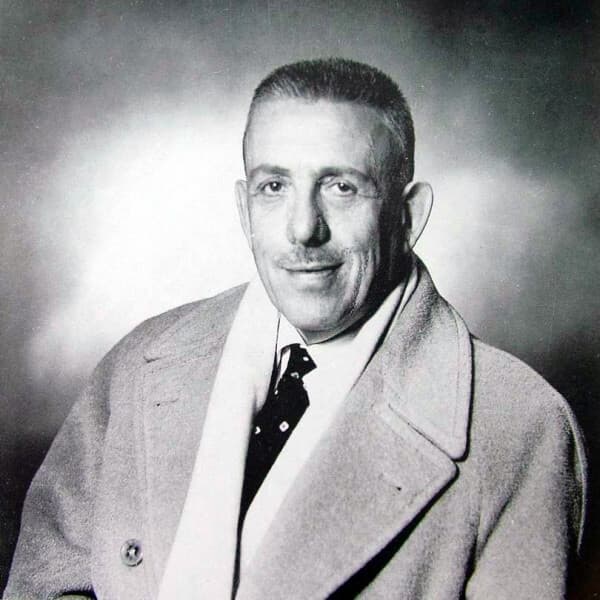

Francis Poulenc

He probably did not expect to die, but as a biographer writes, “the heavy dose of mood-altering drugs he had gobbled for years, may have weakened his heart.” There might have been some hereditary reasons for the heart attack as well, as his father had died at almost the same age. Just a couple of days before his death, he accompanied Duval in a recital at Maastricht, and sent her flower to her hotel with the note “My Denise, I owe you my last joy.” The funeral took place on 2 February 1963 at Saint-Sulpice, and in compliance with his wishes, none of his music was performed. Marcel Dupré played works by Bach on the grand organ of the church, and Poulenc was buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery, alongside his family.

Francis Poulenc: Sonata for Oboe and Piano

Poulenc’s Enigmatic Personality

Poulenc and Denise Duval

His longtime friend and fellow composer Ned Rorem offered a telling description of Poulenc’s enigmatic personality. “Like his name, he was both dapper and ungainly. His clothes came from Lanvin but were un-pressed; his hands were scrubbed, but the fingernails were bitten to the bone. His physiognomy showed a cross between weasel and trumpet and featured a large nose through which he wittily spoke. His sun-swept apartment on the Luxembourg was elegantly toned in orange plush, but the floors squeaked annoyingly. His social predilections were for duchesses and policemen, though he was born and lived as a wealthy bourgeois. His villa in Noizay was austere and immaculate but surrounded by densely careless arbors. There he wrote the greatest vocal music of our century, all of it technically impeccable and truly vulgar. He was deeply devout and uncontrollably sensual. In short, his aspect and personality, taste and music, each contained contrasts, which were not alternating but simultaneous.”

Francis Poulenc: Sept répons des ténèbres

Poulenc: Most Eclectic Composer Who Ever Lived

Milhaud, Cocteau and Poulenc in later years

To be sure, Poulenc’s music and personality mirror the often-conflicting nature of humanity. Simultaneously earthy and refined, a promiscuous homosexual who fathered a daughter late in his life, he was a modern urbane composer who was unafraid to indulge his urges for nostalgia and for mystic spirituality. As a critic once famously remarked, “Poulenc’s music may lie in the gutter, but it is always looking at the stars.” And Jessica Duchen described Poulenc as “a fizzing, bubbling mass of Gallic energy who can move you to both laughter and tears within seconds. His language speaks clearly, directly, and humanely to every generation.” For a good number of critics, musicologists, and composers, Poulenc was probably the most eclectic composer who ever lived, “borrowing disguisedly from a hodge-podge of tried and true languages. Yet in speaking those languages with an accent instantly identifiable as his, he proved them far from exhausted.”

Francis Poulenc: Gloria (Janice Watson, soprano; BBC Chorus; BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Yan Pascal Tortelier, cond.)

Poulenc’s Musical Style

Tomb of Francis Poulenc in Père Lachaise Cemetery

During the later stages of his career, a compelling myth emerged that assumed that music came easily to Poulenc. The composer responded, “the myth is excusable since I do everything to conceal my efforts.” There is no doubt, however, that Poulenc had a beautiful gift for melody. As a scholar writes, “For Poulenc, the most important element of all was melody and he found his way to a vast treasury of undiscovered tunes within an area that had, according to the most up-to-date musical maps, been surveyed, worked and exhausted.”

And let us not forget that the purely melodic associations of the human voice always inspired Poulenc’s music. Poulenc never claimed to have invented a new harmonic language but was content to use conventional harmony. However, “his use of harmony is so individual, so immediately recognizable as his own, that it gave his music freshness and validity.” Poulenc was a painstaking craftsman, and to pianist Pascal Rogé, “both sides of Poulenc’s musical nature were equally important: You must accept him as a whole. If you take away either part, the serious or the non-serious, you destroy him. If one part is erased you get only a pale photocopy of what he really is.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Francis Poulenc: Sonata for Clarinet and Piano