On the occasion of the recent wedding of Louis XV and Maria Leszczyńska, daughter of the deposed king of Poland, the Hamburg Opera am Gänsemarkt saw the premiere of Georg Philipp Telemann’s intermezzos Pimpinone on 27 September 1725. The Telemann intermezzos featured as interludes to Georg Friedrich Handel’s opera seria Tamerlano, and the tree-part interludes were highly popular because it took a pointed and realistic look at contemporary life.

Georg Philipp Telemann: Pimpinone, “Wilde Hummel”

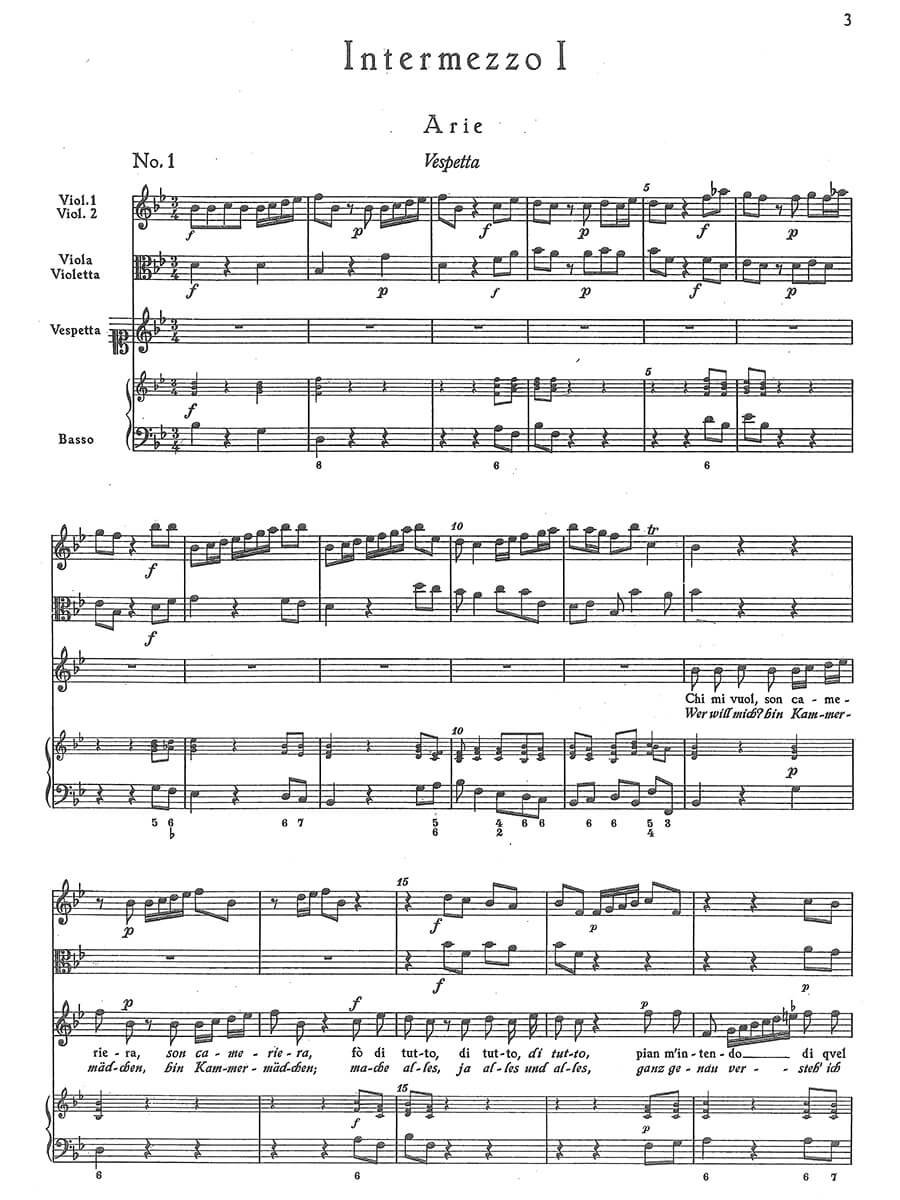

Intermezzo 1

Georg Philipp Telemann

The domestic helper Vespetta is being introduced to the rich and aging merchant Pimpinone. She praises her virtues required for a chambermaid, including modesty and her willingness to work. Pimpinone is pleased, as he hopes that Vespetta will also provide him with sexual services. He had heard that her previous mistress was jealous of Vespetta, and she knows how to flatter the old man in order to get hired.

As a young woman from the lower classes, Vespetta knows that she has to provide services to well-off men, in both the household and in bed, to secure her livelihood. She also understands that her capital is her youth, her labour, her body, and her sexuality. A wealthy employer from a higher class of society would be ideal.

Georg Philipp Telemann: Pimpinone, “Intermezzo 1” (Marie-Sophie Pollak, soprano; Dominik Köninger, baritone; Berlin Akademie für Alte Musik; Georg Kallweit, cond.)

Intermezzo 2

Telemann’s Pimpinone album cover

After working to Pimpinone’s satisfaction for a while, Vespetta wants to be legally entitled to take part of his wealth. And she already understands that this is only possible as a married woman. Vespetta pretends that she wants to leave Pimpinone, but he reacts quickly by showing her the ring and earrings he has just bought. However, Vespetta does not want to be just a mistress, and turns him down.

Pimpinone finally understands, and he is desperate to marry Vespetta, but only if she, as his wife, renounces all amusements and fully obeys him. He offers her a gift of 10,000 thalers as a dowry but only on the condition that she remains at home and entertains no visitors. After some apparent contemplation, Vespetta agrees.

Georg Philipp Telemann: Pimpinone, “Intermezzo 2” (Marie-Sophie Pollak, soprano; Dominik Köninger, baritone; Berlin Akademie für Alte Musik; Georg Kallweit, cond.)

Intermezzo 3

We find Vespetta and Pimpinone married, but their marital life is anything but fun. Vespetta is ready to enjoy her freedoms allowed by her new status, and she feels no longer bound to previous agreements. Pimpinone, on the other hand, wants to control her according to old traditions, and even a visit to her godmother arouses Pimpinone’s jealousy. The situation quickly escalates, as Pimpinone reminds her of her promise to obey him, and Vespetta declares that through marriage, the difference in class has been annulled.

As she declares, “I have chosen you despised marital bed to gain more freedom / I will do my duty as your spouse, but I am not chained as a slave.” She tells him that in future, she would like to go to the opera, dance, speak French, play cards and insists on equal rights. Pimpinone confesses that he loves Vespetta, and she points to the cleverly written marriage contract, which provides her with the dowry in the event of a divorce. The intermezzo ends in a furious argument with no happy end in sight.

Georg Philipp Telemann: Pimpinone, “Intermezzo 3” (Marie-Sophie Pollak, soprano; Dominik Köninger, baritone; Berlin Akademie für Alte Musik; Georg Kallweit, cond.)

Musical Setting

Telemann’s Pimpinone

The trope of the leering old man of wealth and a young woman of a lower social class in an eternal struggle for powers, was very popular. And Telemann knew exactly how to musically handle this situation. Many arias and duets unfold in a parlando style, which would subsequently become the hallmark of opera buffa. As an annotator wrote, “Telemann proves to be a master at musical sketches of moods, situations and people in these scenes from a marriage.”

Telemann skilfully exaggerates individual works, or even stops the flow of words completely, particularly in Pimpione’s arias. And the composer takes great care to musically illustrate the relationship. The first intermezzo “ends with a duet that appears joyful, as both are tiptoeing around each other, but in a predictable progression, by the end of their forth duet, the separation is final. Telemann also composes agile recitatives that translate everyday speech for the stage, and the work features some deliciously funny scenes.

Telemann’s thoughtful setting was highly successful and pointed the way forward to later intermezzi, particularly to Pergolesi’s famous La serva padrona.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter