Gustav Mahler in New York

After listening to Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, the American physician and poet Lewis Thomas wrote an essay that addresses the anxieties produced by the development of nuclear weapons. “I cannot listen to Mahler’s Ninth with anything like the old melancholy mixed with the high pleasure I used to take from this music. There was a time, not long ago, when what I heard, especially in the final movement, was an open acknowledgement of death and at the same time a quiet celebration of the tranquility connected to the process. I took this music as a metaphor for reassurance… Now I hear it differently. I cannot listen to the last movement of the Mahler Ninth without the door-smashing intrusion of a huge new thought: death everywhere, the dying of everything, the end of humanity. The easy sadness expressed with such gentleness and delicacy by that repeated phrase on faded strings, over and over again, no longer comes to me as old, familiar news of the cycle of living and dying. All through the last notes my mind swarms with images of a world in which the thermonuclear bombs have begun to explode in New York and San Francisco, in Moscow and Leningrad, in Paris, in Paris, in Paris. In Oxford and Cambridge, in Edinburgh…”

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 9 – I. Andante comodo (Columbia Symphony Orchestra; Bruno Walter, cond.)

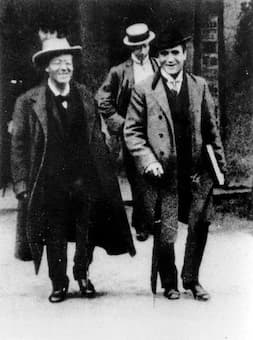

Gustav Mahler and Bruno Walter, 1908

The work was premiered on 26 June 1912, at the Vienna Festival by the Vienna Philharmonic conducted by Bruno Walter. Alban Berg suggested, “The entire first movement is permeated by the premonition of death… Premonition becomes certainty, when in the midst of the deepest and most painful joy in life, death announces itself with greatest force.” Berg is undoubtedly alluding to the fact that Mahler, who died in May 1911, never heard his Ninth Symphony performed. As such, commentators have habitually interpreted the work as Mahler’s conscious farewell to the world. It was composed, after all, following the death of his beloved daughter Maria Anna in 1907 and the diagnosis of his fatal heart disease. On the heels of the spiritual affirmation conjured in his Eight Symphony, we find a Ninth that descends into the darkest crevasses of hell. Mahler returned to a four-movement design, yet arranged them in a rather peculiar way. Enormous slow outer movements frame a pair of vividly contrasting scherzos. It has been suggested that the order of movements represents the classic pattern of reaction to grief: denial, anger, resignation and acceptance. As such, Mahler’s Ninth Symphony is the emotional focus of his last-period trilogy, with Das Lied using poetic terms to evoke the shadow of death, and the incomplete Tenth Symphony supposedly rising above the depths of despair.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 9 – II. Im Tempo eines gemächlichen Ländlers – Etwas tappisch und sehr derb (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Roger Norrington, cond.)

Mahler’s Komponierhäuschen in Toblach

After completing his first full season in New York, Mahler returned to Europe in May 1908, and Alma described “the saddest summer they ever spent together. “We were afraid of everything. He was always stopping on a walk to feel his pulse and he often asked me to listen to his heart and see whether the beat was clear or rapid or calm.” In this atmosphere of persistent gloom, Mahler completed his setting of Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth), and apparently began to draft a new symphony. Once he returned to Toblach a year on, he earnestly set to work on a composition Deryck Cooke describes as “goalless hedonism that becomes a mere starting-point for vanishing bitterness and horror with terrible violence, leading to ultimate heartbreak.” This symphony, which Mahler designated as his No. 9 was the last score he completed. It was also the last of Mahler’s completed scores presented to the public, which undoubtedly contributed to the suggestion that the work represents his musical farewell to life.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 9 – III. Rondo-Burleske: Allegro assai (Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Gustavo Dudamel, cond.)

Gustav and Alma in Toblach

The opening “Andante comodo” has been described as Mahler’s greatest achievement in symphonic compositions. A vast canvas of bare isolation accelerates towards a tormented climax that is unable to find resolution. Tellingly, after a catastrophic collapse, the movement disintegrates into utter nothingness. If the opening movement had taken us into the tortured and tormented internal world of Mahler’s psyche, the second movement returns us to the Austrian countryside. What should have been a symbol of the simplicity and joy of life now becomes the expression of bitterness and anger. Almost a caricature of itself all joy seems to have vanished, and the “Rondo-Burleske” also disintegrates into calculated chaos. This movement, which has been described as “Mahler’s most modern movement,” comes to a crashing conclusion. To balance, or better yet, to complete the first movement, Mahler turns once more to an “Adagio” conclusion. Besides quoting a passage from his “Songs on the Death of Children,” the last two pages of the score last for almost six minutes. It was Leonard Bernstein who suggested that this movement symbolically prophesized three kinds of death; “Mahler’s own impending death, the death of tonality, and the death of Western culture in all the arts.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 9 “Adagio”