Ralph Vaughan Williams, 1954

Ralph Vaughan Williams enjoyed excellent health throughout his life, and at the age of 85 he has just completed the piano score of his new opera Thomas the Rhymer. He also planned two song cycles for voice and piano, to poems by his wife, and of these the completed items were published posthumously as Four Last Songs. His Cello Concerto was in an advanced stage of work, and he discussed with his publisher a new and revised edition of Hugh the Drover, on which he had worked along with his Ninth Symphony. As he went to bed on the evening of 25 August 1958, he was contemplating the recording session for this Ninth Symphony that he would attend the following day, however, he died suddenly in the early hours of 26 August 1958 at Hanover Terrace. In one of his last public statements shortly before his death he said, “Bach was behind the times, Beethoven was ahead of them, and yet both were great composers. Modernism and conservation are irrelevant. What matters is to be true to oneself.”

Ralph Vaughn Williams: Four Last Songs

Simona Vere Pakenham © John Vickers

A close friend of the composer and his wife Ursula, Simona Vere Pakenham wrote a touching account of Vaughan Williams’ death and funeral service. “Ursula rang, considerably before breakfast, to tell us that Ralph had died in the night… The gap between August 26th, when Ralph had died, and the funeral on 19th September seemed interminable. All his friends were shaken as well as full of grief. When he was alive I had thought of him as old—his snow-white hair, which stood out in a crowd like Persil advertisements, so you could tell at a glance whether he was in a concert audience, was enough to remind you of that fact. But one’s immediate reaction to the news was how could he have died so young? There was almost a feeling of annoyance as he had no right to leave us so suddenly and when he seemed in such a creative mood.” Pakenham continues, “Of the funeral itself I have subdued and misty recollections. The day was grey and drizzly, the interior of the Abbey somber. Almost everybody had dressed in black, which did not seem appropriate for Ralph.”

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus (Susan Lynn, violin; Thomas Waddington, cello; Audrey Douglas, harp; English String Orchestra; William Boughton, cond.)

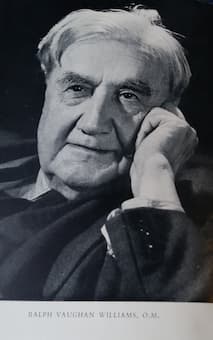

Ralph Vaughan Williams

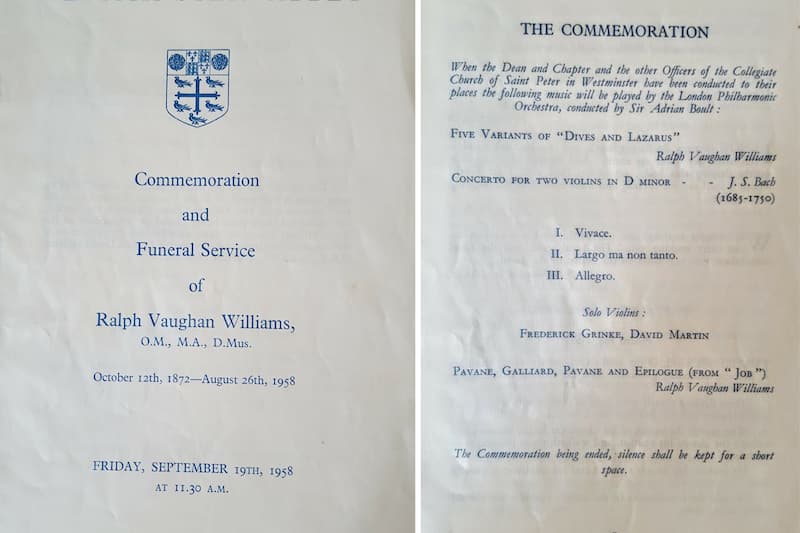

Sir Adrian Boult conducted the Commemoration, a concert of music by Ralph Vaughan Williams and his favorite composer, Johann Sebastian Bach. Pakenham reports, “I do not know who had decided to open the proceedings with the Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus. The opening bars of that lovely and so English tune were enough to undo all our resolutions of dignity and a good many of us, despite our resolutions, dissolved into tears. I have a persistent memory of the Tallis Fantasia following, but it is not included in the Order of Service. Can I have dreamt it? The Order of Service did however, include the Concerto for Two Violins in D minor by J.S. Bach, and the Pavane, Galliard, Pavane and Epilogue from Job by Vaughan Williams. Pakenham’s most vivid memory of the actual funeral was of Ursula’s deportment. “In a simple dress of charcoal grey, hatless and carrying only a small sprig of green leaves, she led the principal mourners, following the clergy procession into the Musician’s Aisle to lay his ashes near to Purcell and his teacher Stanford.”

Ralph Vaughn Williams: Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis (Sinfonia of London; John Barbirolli, cond.)

Music played at Vaughan Williams’ funeral and commemoration

Ralph Vaughan Williams’ statue in Dorking

The choir sang “O Taste and See” which RVW had written only five years earlier for the same abbey but a very different occasion. “Then when the small procession had returned, we ended with the marvelously uplifting arrangement of the “Old Hundredth” which he had persuaded the Archbishop to allow in that same ceremony in order that the congregation could get to their feet and add their voices to those of the choir. That was precisely what was needed to send us out more happily into the grey afternoon.” The Musical Times obituary noted “that in his music he expressed the essential spirit of England as perhaps no other composer has ever done before, one where rugged optimism and an unflinching commitment to human decency were defining characteristics.” The music of Ralph Vaughan Williams struggled to gain acceptance, as the composer was long perceived as “a primitive musician wrestling interminably with his lack of technique and somehow, with immense effort, emerging with a rough-hewn masterpiece ready for the publishers.” Vaughan Williams himself was his harshest critic as he wrote, “I wish I didn’t dislike my own stuff so much when I hear it—it all sounds so incompetent… But in the next world I shan’t be doing music, with all the striving and disappointments. I shall be being it.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Symphony No. 9

“a primitive musician wrestling interminably with his lack of technique”

Words that could not be further from the truth. RVW was a supreme composer and knew his stuff backwards. He built symphonies with the skill of a precision craftsman and was clearly self critical and at pains to get the best possible result, which is often deeply emotional.

If I could only listen to one composer for the rest of my life, I’d pick Ralph in a flash. I don’t think anyone wrote for strings as effectively and emotionally as he.

Indeed. Views, perhaps, that reflect the musical snobbbery of the time.