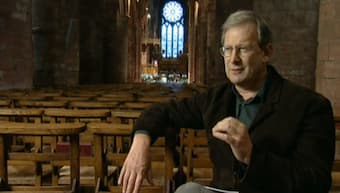

John Eliot Gardiner

John Eliot Gardiner, born on 20 April 1943, is revered as “one of the world’s most innovative and dynamic musicians, constantly in the vanguard of enlightened interpretation and standing as a leader in contemporary musical life.” He founded and artistically directed the Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique. Well-known for his performances of the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, Gardiner is a key figure in the early music revival and a pioneer of historically informed performances. Gardiner’s obsession with Bach culminated in 2000, when he and his musical forces traveled around Europe and the U.S. performing all of Bach’s sacred cantatas on their appropriate Sundays in different churches. And he crowned his achievements in 2013, publishing his book Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven, a project 12 years in the making. Wanting to get to know Bach the man better, he found an individual with anger management issues, and yet with a great capacity for tenderness. “Bach had normal flaws and failings, which make him very approachable. But he had this unfathomably brilliant mind and a capacity to hear music and then to deliver music that is beyond the capacity of pretty well any musician before or since.”

John Eliot Gardiner: Bach’s “Christ lag in Todesbanden” BWV 4

Gardiner was born in Fontmell Magna, Dorset to Rolf Gardiner and Marabel Hodgkin. As a child, he became a member in the local church choir and he taught himself how to play the violin. He was educated at Bryanston School before reading history and Arabic at King’s College, Cambridge. Gardiner also studied music with Thurston Dart, conducting with George Hurst, and composition with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. As a student at King’s he founded the Monteverdi Choir for a one-off performance of Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 at Kings College Chapel Cambridge in 1966. The performance was immensely popular and Gardiner made his conducting début at the Wigmore Hall in London in the same year. For a Proms concert in 1968, Gardiner founded, as a complementary body to the choir, the Monteverdi Orchestra. “He drew from his singers a then unfashionable brightly focused tone in the Continental tradition, bringing to their Baroque repertory an unaccustomed clarity and incisiveness. These qualities decisively influenced other groups in the ongoing search for an ‘authentic’ performing style.”

Gardiner was born in Fontmell Magna, Dorset to Rolf Gardiner and Marabel Hodgkin. As a child, he became a member in the local church choir and he taught himself how to play the violin. He was educated at Bryanston School before reading history and Arabic at King’s College, Cambridge. Gardiner also studied music with Thurston Dart, conducting with George Hurst, and composition with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. As a student at King’s he founded the Monteverdi Choir for a one-off performance of Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 at Kings College Chapel Cambridge in 1966. The performance was immensely popular and Gardiner made his conducting début at the Wigmore Hall in London in the same year. For a Proms concert in 1968, Gardiner founded, as a complementary body to the choir, the Monteverdi Orchestra. “He drew from his singers a then unfashionable brightly focused tone in the Continental tradition, bringing to their Baroque repertory an unaccustomed clarity and incisiveness. These qualities decisively influenced other groups in the ongoing search for an ‘authentic’ performing style.”

John Eliot Gardiner: Monteverdi’s “Verspers”

Gardiner was drawn to historical instruments because of their capacity to emulate the human voice. “I think it’s like a conversation between a different group of people sitting down to have a political argument. Sometimes they’re strident, and sometimes they’re caressing and trying to persuade in a more gentle way, but there is this sense of conflict and struggle, of pulling and pushing all the time, elasticity of dialogue and dialectic. And these instruments can do that.” Gardiner has an exceptional feeling for dramatic pacing and effect, so it was a natural progression to turn towards opera. He made his opera debut in 1969 with a performance of Mozart’s The Magic Flute at the English National Opera. Four years later, in 1973, he made his first appearance at the Covent Garden conducting Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride. In fact, from 1983 to 1988 he was music director of the Lyons Opéra, introducing several rare works there, including Charpentier’s Médée and Leclair’s Scylla et Glaucus. Gardiner’s reputation was initially based on performances with period instruments, but his over 250 recordings reflect the breath of his repertory.

Gardiner was drawn to historical instruments because of their capacity to emulate the human voice. “I think it’s like a conversation between a different group of people sitting down to have a political argument. Sometimes they’re strident, and sometimes they’re caressing and trying to persuade in a more gentle way, but there is this sense of conflict and struggle, of pulling and pushing all the time, elasticity of dialogue and dialectic. And these instruments can do that.” Gardiner has an exceptional feeling for dramatic pacing and effect, so it was a natural progression to turn towards opera. He made his opera debut in 1969 with a performance of Mozart’s The Magic Flute at the English National Opera. Four years later, in 1973, he made his first appearance at the Covent Garden conducting Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride. In fact, from 1983 to 1988 he was music director of the Lyons Opéra, introducing several rare works there, including Charpentier’s Médée and Leclair’s Scylla et Glaucus. Gardiner’s reputation was initially based on performances with period instruments, but his over 250 recordings reflect the breath of his repertory.

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Iphigénie en Tauride (Diana Montague, mezzo-soprano; John Aler, tenor; Thomas Allen, baritone; Rene Massis, baritone; Monteverdi Choir; Lyon National Opera Orchestra; John Eliot Gardiner, cond.; Lucinda Houghton, soprano; Nancy Argenta, soprano; Suzanne Flowers, soprano; Carol Hall, mezzo-soprano; Nicola Jenkin, soprano; Jean Knibbs, soprano; Rachel Platt, soprano; Mary Seers, soprano; René Schirrer, bass; Sophie Boulin, soprano; Danielle Borst, soprano; Collete Alliot-Lugaz, soprano; Jane Armstrong, soprano)

In 1990, Gardiner formed a new period-instrument orchestra, the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, to perform music of the 19th century. To commemorate the 250th birthday of Ludwig van Beethoven, Gardiner channeled the grandeur and passion of Beethoven’s symphonic work into a performance medium that would have been familiar to the composer: valveless brass, woodwinds without additional keys and levers, gut strings, and hide-covered timpani struck with hard sticks.

In 1990, Gardiner formed a new period-instrument orchestra, the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, to perform music of the 19th century. To commemorate the 250th birthday of Ludwig van Beethoven, Gardiner channeled the grandeur and passion of Beethoven’s symphonic work into a performance medium that would have been familiar to the composer: valveless brass, woodwinds without additional keys and levers, gut strings, and hide-covered timpani struck with hard sticks.

For Gardiner, “Beethoven was an allusive man and composer, brought up in a very humanistic and intellectually stimulating environment in Bonn. He had a constant need to use music as a tool, as a weapon, as a vehicle for the transmission of revolutionary thoughts.” The mission of the ORR was trying to recover the world of the Beethoven sound, “which is a tricky thing to do because Beethoven was largely deaf for the last part of his life.” However, according to Gardiner, “Beethoven had such an acute inner ear that he could reconstruct the sounds he’d learned when he was growing up in Bonn and was a viola player. And he had such an extraordinary ability to retain that when he couldn’t actually hear the sounds of his own orchestra. And yet he expanded the expressive range and the color spectrum of an orchestra in the most amazing and joyous way.” Gardiner has received more Gramophone awards than any other artist. He has also received an honorary doctorate from the University of Lyons, has been created a Commander of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and is an honorary fellow of King’s College, London, and the RAM. He was made a CBE in 1990 and knighted in 1998.

For Gardiner, “Beethoven was an allusive man and composer, brought up in a very humanistic and intellectually stimulating environment in Bonn. He had a constant need to use music as a tool, as a weapon, as a vehicle for the transmission of revolutionary thoughts.” The mission of the ORR was trying to recover the world of the Beethoven sound, “which is a tricky thing to do because Beethoven was largely deaf for the last part of his life.” However, according to Gardiner, “Beethoven had such an acute inner ear that he could reconstruct the sounds he’d learned when he was growing up in Bonn and was a viola player. And he had such an extraordinary ability to retain that when he couldn’t actually hear the sounds of his own orchestra. And yet he expanded the expressive range and the color spectrum of an orchestra in the most amazing and joyous way.” Gardiner has received more Gramophone awards than any other artist. He has also received an honorary doctorate from the University of Lyons, has been created a Commander of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and is an honorary fellow of King’s College, London, and the RAM. He was made a CBE in 1990 and knighted in 1998.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

John Eliot Gardiner: Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 5”