John Collier: Priestess of Delphi (1891)

(Art Gallery of South Australia)

Zeus sent out two eagles and where their paths crossed was the center of the world. At that center, Delphi the Oracle, made her pronouncements. You could seek guidance from her, but the interpretation of what she said was up to you.

Everyone sought the Oracle’s guidance and brought fantastic treasures to Delphi in her honour. Each city state built its own treasury to show its wealth and power. Delphi became a place only for archaeologists – earthquakes and rock falls destroyed the temple complex under Mount Parnassus, and it was only in the late 19th century that it was uncovered. Now, it’s all a ruin, to be visited by those with a sense of history.

The Athenian Treasury at Delphi

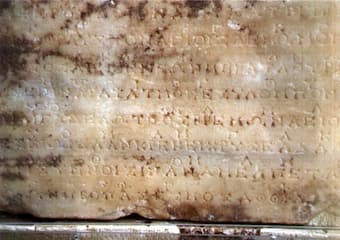

The oldest pieces of notated music were found at Delphi, dating from 128 BCE. The two pieces were found carved into the wall of the Athenian Treasury at Delphi and transcribed by Théodore Reinach. The First Delphic Hymn uses vocal notation, and the Second Delphic Hymn uses instrumental notation. The composer of the first hymn is thought to be Athēnaios Athēnaiou (Athénaios, son of Athénaios), a singer, hence the vocal notation. The composer of the second hymn is ascribed to Limēnios, son of Thoinos, a kithera player.

Each of the Delphic hymns starts with an invocation of the Muses to descend from their home above Delphi on Mount Parnassus and to join the procession to celebrate their brother Apollo.

The music annotation: the small symbols above the text indicate the pitches

French archaeologist Annie Bélis used her musical training to write about the music of classical antiquity. She founded the Ensemble Kérylos to perform the music she was writing about and here, they perform the first Delphic Hymn. Since we know nothing about performing practice in the first centuries BCE, we can only guess at how this might have been sung.

Her performance includes both the paean, made up of 3 verses of 9 lines apiece, and the hyperchemie / hyporchema, a dance with 9 more lines of text. Nearly all of the hyperchemie is lost.

Anonymous: Delphian Hymns to Apollo: Athenaios, Son of Athenaios: Pæan and Hyperchemie (Jerome Correas, bass-baritone; Ensemble Kérylos; Annie Bélis, cond.)

The second Delphic hymn is made up of 10 sections – 9 sections for the paean and 1 section for the prosodion. As with the first Delphic Hymn, there are breaks where the stone is missing.

Anonymous: Delphian Hymns to Apollo: Limenios, Son of Thoinos: Pæan and Prosodion (Jerome Correas, bass-baritone; Ensemble Kérylos; Annie Bélis, cond.)

Our lack of knowledge about how these pieces would have been performed has inspired modern composers to take up the melodies and modernize them.

Mark Edwards Wilson wrote a trilogy of works about the three great centres for oracles in the ancient world: Delphic, Dodona, and Siwa. His approach to Delphi takes the Delphic Hymns and uses them as the basis for a set of variations. His emphasis on their non-tonal musical lines gives us the contrast between ancient and modern music.

Mark Edwards Wilson: Delphi: Symphonic Metamorphoses on the Delphic Hymn of Athenaios 128 B.C. (Kiev Philharmonic Orchestra, Robert Ian Winstin, cond.)

Eugène Delacroix: Lycurgus Consulting the Pythia (1835/1845)

(University of Michigan Museum of Art)

That we have musical scores from two thousand years ago is marvel enough. That they continue to inspire composers today is a wonderful evocation of the past into today. Wilson’s work in particular, with its alternating tonalities, helps us see into the past with today’s lenses.

The high priestess at Delphi, called the Pythia, was established in the 8th century BC and continued as an oracle until the late 4th century AD. The oracle appears in literature from Aeschylus to Livy to Xenophon and her pronouncements formed critical elements of stories such as that of Oedipus, who the oracle says will ‘kill his father and marry his mother.’

What would you ask the Oracle? How would you interpret her answer? That remains one of the Delphic mysteries.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Hello! This awesome!

Thank you

*Would it be possible to have the lyrics ?

It is quite hard to understand.

Hi,

You can find the complete lyrics in Greek and English at (http://www.doublepipes.info/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Athenaios-Paean-DRAFT-7-May-2017.pdf) .

The Wikipedia page (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delphic_Hymns ) also shows you the original marble engravings, now at the Delphi Archaeological Museum.