Prior to his transformation of operatic thought via the notion of the “Gesamtkunstwerk,” a concept that attempted to achieve a synthesis of poetic, visual, musical, and dramatic arts, Richard Wagner was predominantly known as an opera composer in the romantic tradition. Much of the score of Tannhäuser belongs to that tradition as Wagner expands mid-19th century models of “melody, harmony, and form to take his music to unprecedented expressive heights, both in the vocal and orchestral writing.” For his libretto, Wagner blended together three legends, including the saga of a 13th-century German Minnesänger and poet named Tannhäuser.

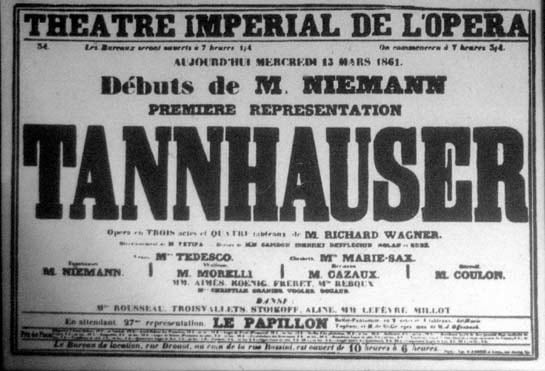

Poster of Tannhäuser performance in Paris

The historical Tannhäuser, judging from his poems, was rather fond of the good things in life, “especially wine, good cheer, and love.” As a scholar wrote, “Apparently his sensuousness did not wholly commend itself to his contemporaries, and the legend grew that for having spent a year with Venus the Pope condemned him for his sin to eternal damnation.” Wagner also draws on the “Sängerkrieg,” a minstrel song-singing contest held in 1207 at the Wartburg castle in Thuringia. Whether the contest was purely legend or had some basis in an actual event has been long debated, but Wagner nevertheless wove the story into his operatic narrative.

Richard Wagner: Tannhäuser “Overture”

Richard Wagner, 1861

And then there is the mythical grotto of Venus, the goddess of love. The original title of the opera had been “The Hill of Venus,” but the eventual publisher strongly objected and explained to the composers, “since you do not mix with the public, you have no idea what horrible jokes were made about this title; these jokes, he thought, must come from the professors and students of the Medical School in Dresden, as they had a special talent for that kind of obscene joke.”

John Collier: Tannhäuser en el Venusberg

The “Venusberg,” designates the legendary dwellings of Lady Venus, who luxuriously holds court with nymphs and mermaids inside the mountain named after her. She attracts men with her beauty, entices them to a life of pleasure and sin, and as such, to eternal damnation. That particular myth had been around since the Middle Ages, but Wagner found the actual location near the Wartburg Castle in Thuringia. He identified the “Venusberg” with the “Hörselberg” hills near Eisenach and the Wartburg Castle. The final piece for Wagner’s libretto draws on Saint Elizabeth of Thuringia, who married at the age of 14, and widowed at 20. She used her money to build a hospital and became a symbol of Christian charity after her death at the age of 24. And did I mention that Saint Elizabeth actually lived as the wife of the Landgrave of Thuringia in the Wartburg Castle?

Richard Wagner: Tannhäuser, “Venusberg Music”

Basically, the Tannhäuser character is torn between his love for the virginal Elisabeth and the goddess of love Venus, a dilemma he confesses at a singing competition. For Wagner, Tannhäuser narrates a story of sacred and profane love, and the ultimate redemption through love. While Wagner was composing the music for the Venusberg grotto, he “grew so impassioned that he made himself ill.” He wrote in his autobiography, “With much pain and toil I sketched the first outlines of my music for the Venusberg… Meanwhile, I was very much troubled by excitability and rushes of blood to the brain. I imagined I was ill and lay for whole days in bed.”

Wartburg castle in Thuringia

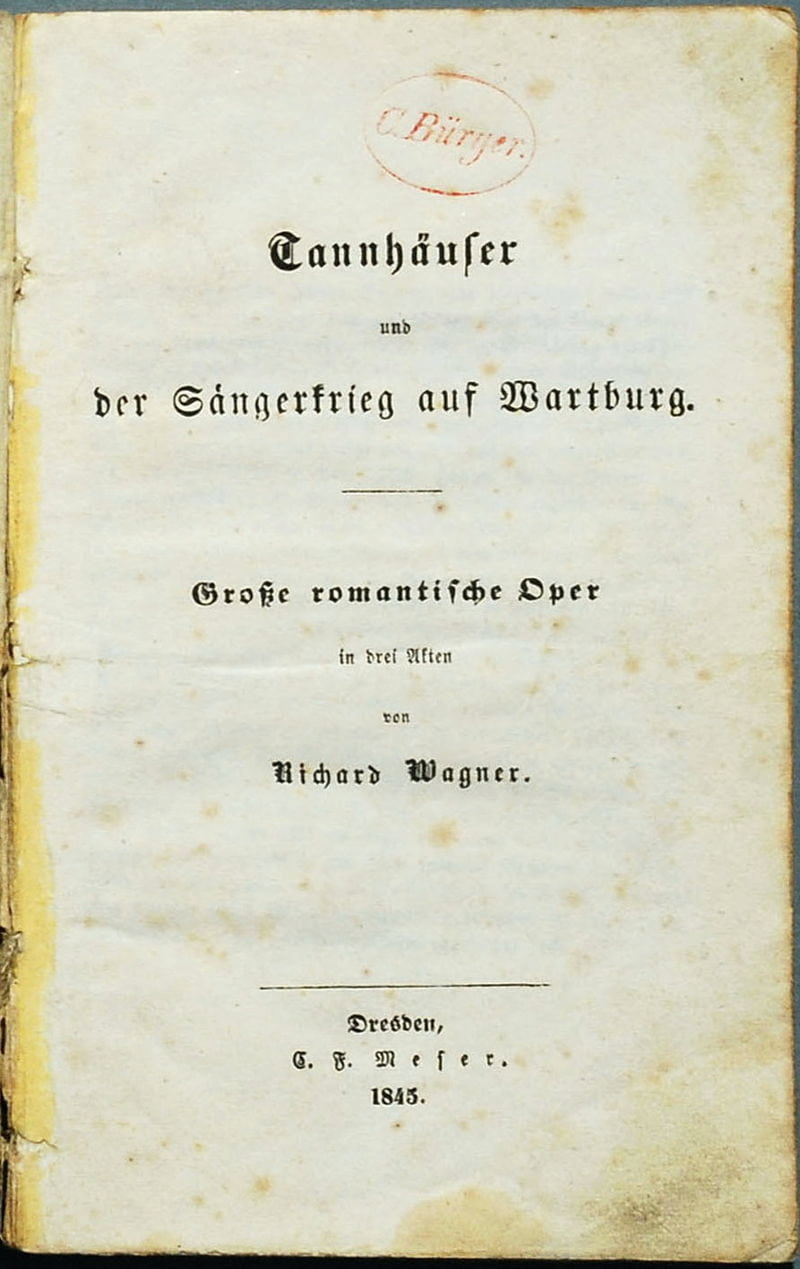

In the event, Wagner himself conducted the world premiere on 19 October 1845 at the Court Opera in Dresden. Originally, he had intended to premiere the opera on 13 October, as his niece Johanna Wagner, who was singing the part of Elisabeth, was celebrating her 19th birthday on that particular day. However, Johanna was ill, so the performance was postponed by six days. On that day, Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient sung as Venus, and Josef Tichatschek took the title role of Tannhäuser, but the work failed to make an impression with the audience.

Richard Wagner: Tannhäuser, “Oh! You my beautiful evening star”

Wagner himself was not satisfied and he tinkered with it for decades. It was finally published in 1860 with an alternate ending in what is generally known as the “Dresden Version.” In 1861, Emperor Napoleon III requested Wagner, at the suggestion of the wife of the Austrian ambassador to France, Princess Pauline von Metternich, to stage Tannhäuser at the Paris Opéra. Following the traditions of the opera house, Wagner had to insert the “Venusberg Ballet” into the score. However, rather than putting the ballet in its traditional place in Act II, Wagner selected to place it in Act I, leading to one of the most celebrated débâcles in the annals of operatic history.

Manuscript cover of Tannhäuser, 1845

“Revenging themselves on the politically unpopular Princess Pauline Metternich, who had negotiated the invitation, the members of the Jockey Club disrupted three performances at the Opéra in March 1861 with aristocratic baying and dog-whistles before Wagner was allowed to withdraw the production.” It once and for all ended Wagner’s hopes of establishing himself in Paris. Wagner made even more revisions to the “Paris Version”, particularly to the final scene in what is known as the “Vienna Version” of 1875. You are most likely to hear this particular version in modern performances today. Three weeks before his death in 1883, Wagner told his wife Cosima that he was still dissatisfied with Tannhäuser, and “that he still owes the world the real Tannhäuser.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Richard Wagner: Tannhäuser, “Dich teure Halle”

I still love this opera. Yes is a wonderful play.