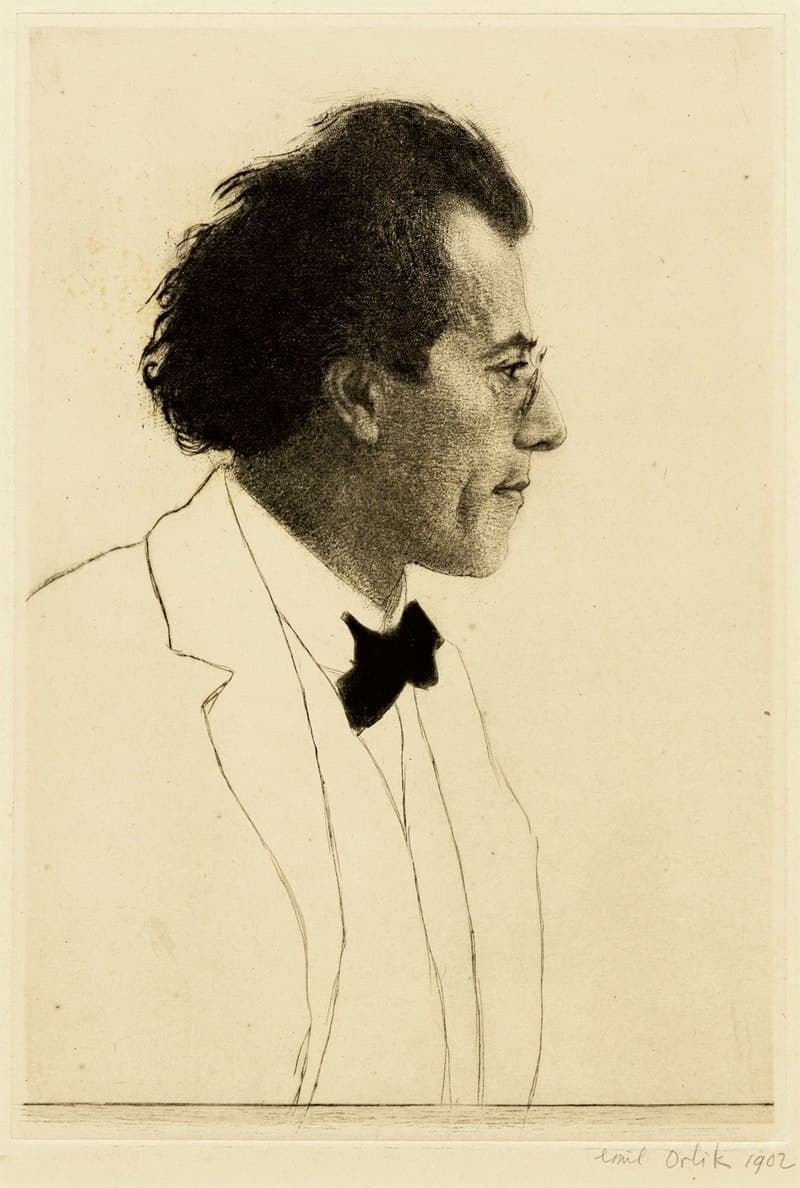

Gustav Mahler

In the afternoon of 24 February 1901, Gustav Mahler conducted the sixth Philharmonic concert in a performance of Bruckner’s Fifth Symphony. Mahler had been unhappy that Bruckner had left so many passages and themes “of a Beethovenian grandeur not carried through, developed and integrated in the whole.” As such, he had made some cuts to the first movement, trying “to eliminate that which is empty and irrelevant.” The performance predictably caused an uproar, and Mahler was accused of “an outrageous lack of regard for his former master, and having smashed the statue with an impious hand, leaving only its torso intact.” An especially vitriolic critic wrote, “The connoisseurs were filled with boundless fury and bitterness at such a shameful mutilation of an immortal creation.” Mahler did not have much time to reflect on the criticism, as he conducted the hundredth-anniversary performance of Die Zauberflöte in the evening. Mahler had been pushing himself very hard, and an audience member noticed “his pale cheeks, those eyes like burning coals,” and commented, “no one can go on like that.”

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor “Funeral march”

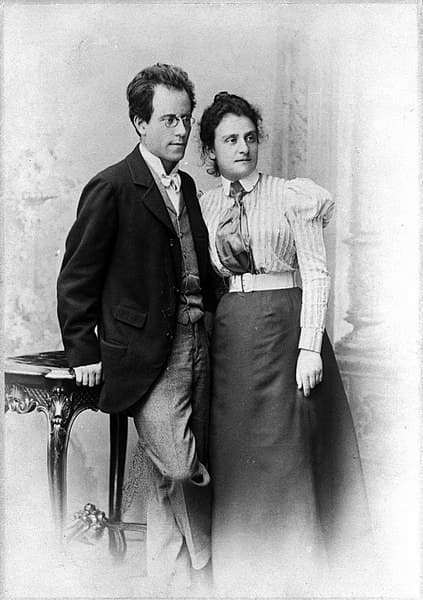

Gustav Mahler with his sister Justine Mahler

During the night, Mahler suddenly collapsed in his apartment. He initially thought the attack would pass, but eventually did phone his sister Justine. She discovered her brother lying in a pool of his own blood and immediately called the family physician Dr. Singer. After an initial examination, it was decided that a surgeon should be notified. Upon arrival, the surgeon told them “that they had taken a terrible risk by not sending for him earlier” and only an emergency operation for an intestinal haemorrhage, located particularly high up in the intestinal tube, saved his life. He subsequently reported to his close friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner: “When I saw the faces of the two doctors, I thought my last hour had come… While I was hovering on the border between life and death, I wondered whether it would not be better to have done with it at once, since everyone must come to that in the end. Besides, the prospect of dying did not frighten me in the least… and to return to life seemed almost a nuisance.”

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor, “Moving stormily, with the greatest vehemence” (Cologne Gürzenich Orchestra; Markus Stenz, cond.)

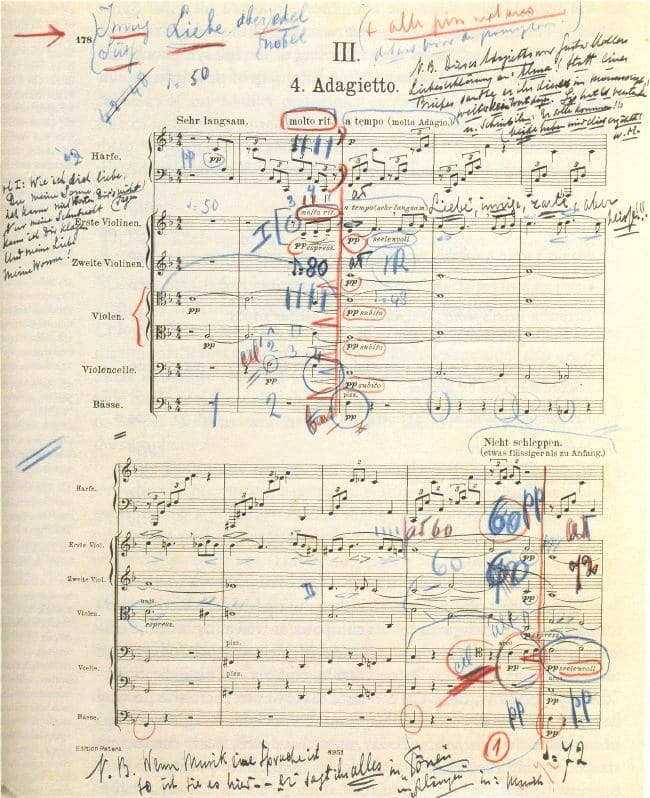

Manuscript of Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 “Adagietto”

This statement of resigned acceptance seems rather curious for a man in his early forties, yet we must remember that thoughts of death had preoccupied the composer since childhood. The second of fourteen children of whom only six survived into adulthood meant that he was part of “a funeral every other week.” Mahler spent the next day weak and in bed, and when the score of his Fourth Symphony was brought to him for corrections, he was horrified to think, “that if I had died last night, the entire structure and significance of the work would have been destroyed by this reversal of the movements.” Mahler recovered rapidly, and the surgeon decided to perform a follow-up procedure about a week later. Expertly performed, “the operation dispelled all anxiety for Mahler’s health,” but since the deterioration of the lining of the intestinal tube was even worse than he had feared, Mahler was prescribed a long period of convalescence. To the outside world, it seemed that Mahler quickly forgot about this life-threatening episode. There can be no doubt, however, that it profoundly changed not only the man but also the composer.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor, “Scherzo” (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Bruno Walter, cond.)

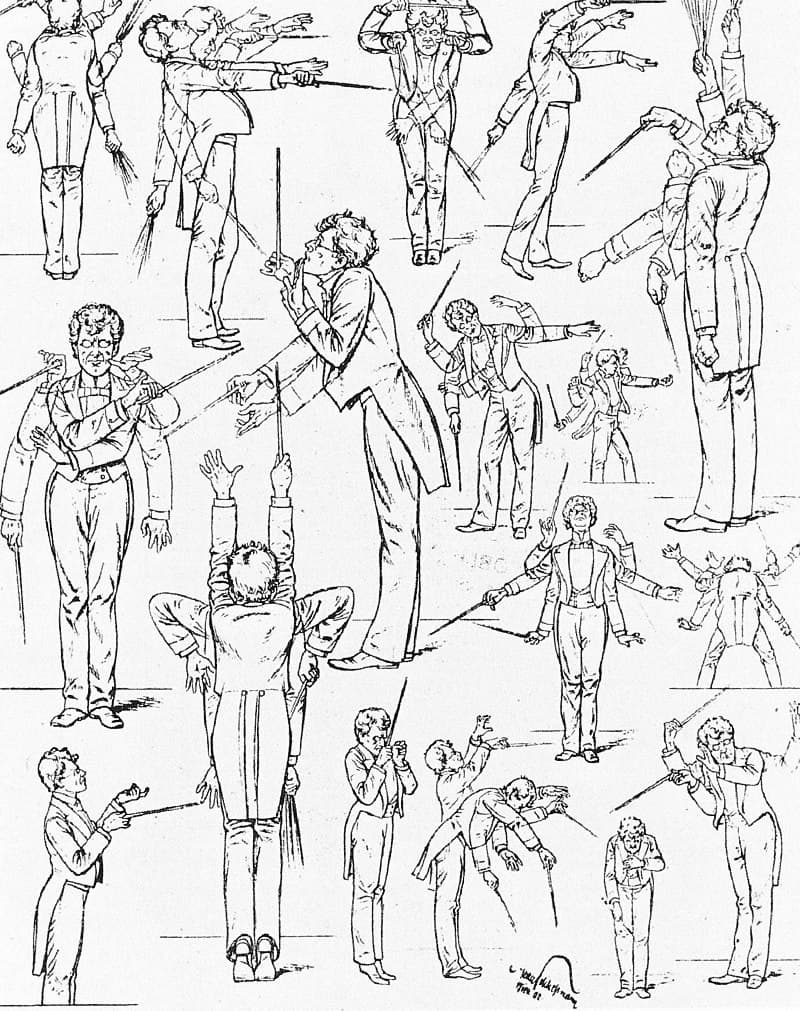

Caricature of Gustav Mahler conducting

Almost immediately, Mahler’s music underwent a profound change. Leaving the fantasy world of the Wunderhorn behind, Mahler soon embarked on a central trilogy of symphonic essays that, according to the composer, represented “a completely new style.” This new direction abandoned the use of voices and poetic texts, which had been an integral part of his earlier symphonies. Adopting a purely instrumental conception, Mahler also rejected the use of specific “programmes,” as he was clearly no longer willing to share written explanations of his works with the public. Poetic influences and the idea of a programmatic symphony had not disappeared, but as Donald Mitchell suggests, “the Fifth Symphony initiated a new concept of an interior drama, and the programme had become internalized.” In addition, his newly discovered admiration for the contrapuntal mastery of J. S. Bach led to an increased emphasis on counterpoint in his own works. In fact, hyperactive motivic counterpoint was to become a hallmark of this “new polyphonic orchestral style.” Bruno Walter remarked, “Mahler was aiming to write music as a musician,” and Arnold Schoenberg suggested that the Fifth Symphony “rightfully belongs to the new music of the twentieth century.”

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor “Adagietto”

Alma Schindler, 1902

Mahler conducted the premiere of his Fifth Symphony on 18 October 1904 with the Gürzenich Orchestra in Cologne. The work unfolds in five movements, but more importantly, the composer divided the symphony into three parts. The opening two movements constitute Part I, the concluding two movements Part III, and the entire Symphony pivots on Part II, a central Scherzo. Furthermore, the first and fourth movements serve as introductions to the second and fifth movements, respectively. As such, the Fifth Symphony is constructed to be symmetrical and concentric at the same time. It has been suggested that the complexity of this structure freed Mahler from the constraints of standard formal conventions. His music “moves from negative emotions towards positive ones” via the central Scherzo, which simultaneously contains “moments of great anxiety and jubilation.” This emotional progression might in fact be entirely autobiographical, with the opening funeral march and raging second movement connected to his life-threatening operation, and the “Adagietto” and concluding “Rondo” representing his love and eventual marriage to Alma Schindler.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor “Rondo-Finale”