The set of Parade, designed by Pablo Picasso

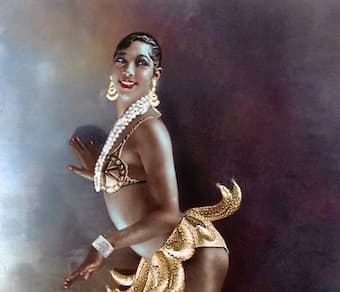

The famed Folies Bergère in Paris was built as an opera house and initially opened its doors by offering performances of light entertainment, including operettas, comic opera, popular songs, and gymnastics. The venue reached the height of its fame and popularity during the “Belle Époque” featuring grand spectacles that included elephants, polar bear and other exotic creatures, including bathing beauties plunging into swimming pools. And you have all heard about the famed Josephine Baker, no doubt. Erik Satie ingeniously transferred this circus atmosphere of the music hall and cabaret into the multimedia spectacle and ballet called “Parade,” which premiered at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris on 18 May 1917.

Erik Satie: Parade – Choral (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Philippe Entremont, cond.)

Josephine Baker

Initially, it was Jean Cocteau who dreamed up a scenario that would almost certainly antagonize and offend the audience. A Chinese magician, a little American girl and acrobats parade outside their tents giving free excerpts from their full performance in an effort to lure the audience into buying tickets. The crowd, however, mistakes their samples for the main show and disappears. To realize his vision of this multimedia spectacle and ballet, Cocteau assembled a unique meeting of the greatest artistic minds offered by Paris at that time. Serge Diaghilev and the “Ballet Russes” commissioned and performed the piece, Léonide Massine provided the choreography, Pablo Picasso designed and painted the costumes and the set—including the red opening curtain, Guillaume Apollinaire wrote the program notes for the first performance and invoked the word “surrealism” for the first time, and the “enfant terrible” of the Parisian café-concert scene Erik Satie composed the music.

Erik Satie: Parade – Prelude du rideau rouge (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Philippe Entremont, cond.)

Ballerina poses for Harry Lachmann for Diaghilev Ballets Russes in Paris 1917

The paradox that lay at the heart of “Parade” was one of Cocteau’s favorite themes. A critic writes “this theme relies on the confusion in the minds of the audience between foretaste and the feast-to-come, between the sideshow and the main event, between the exterior spectacle and the interior one. The hectic advertising meant to lure spectators inside actually holds them outside, sates them prematurely, blunts their curiosity by bludgeoning their senses.” Picasso and Satie rendered this paradoxical relationship between exterior and interior with particular eloquence. Picasso’s red curtain, painted upon a parted curtain revealed the performers at ease backstage. Satie’s musical analogue was to devise a fugal exposition to accompany the “Red Curtain,” an interiorized musical style to accord with the glimpse of the stage interior. As Picasso’s curtain rises, the musical style becomes extroverted and popular by including marches, waltzes and the ragtime song.

Erik Satie: Parade – Prestidigitateur Chinois (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Philippe Entremont, cond.)

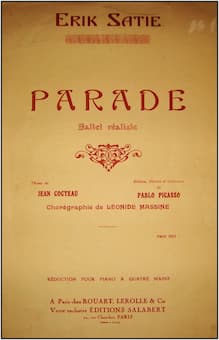

Erik Satie’s Parade 1st edition

By relying on the vitalizing potential of the “everyday” made visible in the appropriations of imported popular dances, Satie transformed Cocteau’s jumble of impressions into the most imposing piece of musical architecture. Satie relied on the basic structural pattern of the “3 Pieces in the Shape of a Pear,” placing three central numbers within a dual frame, that is, a twofold preliminary and a twofold conclusion. Each of the music hall numbers is framed with recurring entrance and exit music for the characters in question. The supreme effort and disappointment of the managers employs the same motivic material as the entrance of the manager, and the final movement entitled “Following the prelude of the Red Curtain” completes the prelude of the red curtain heard as the opening number.

Erik Satie: Parade – Petite fille Americaine (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Philippe Entremont, cond.)

Ballet costumes of Parade

Besides featuring a typewriter, pistol shot and sirens, the Little American girl also dances a lugubrious ragtime. This dance, which actually quotes Irving Berlin’s “That Mysterious Rag,” published in 1911, mirrored the craze for American popular music that would soon reach a feverish peak in Europe around 1920. Furthermore Cocteau’s notion of American womanhood, which was surely inspired by Hollywood heroines like Mary Pickford and Pearl White, involved a high degree of athleticism, and unselfconscious sex appeal. She swims, boxes, dances, leaps onto moving trains, Cocteau writes, “all without knowing that she is beautiful.” Maria Chabelska, who interpreted Satie’s ragtime music with great charm and gusto brought the dance to a poignant conclusion when, thinking herself a child at the seaside, she ended up playing in the sand.

Erik Satie: Parade – Acrobates (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Philippe Entremont, cond.)

In the movement entitled “Acrobats,” Satie employs large intervallic leaps in the upper register that are bitonally projected against a marching bass line to produce a lurching waltz tune. Satie’s effort in composing music for the seven sections of “Parade” earned him the unflattering label, the composer for typewriters and rattles.

Erik Satie: Parade – Final (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Philippe Entremont, cond.)

The first performance of “Parade” was drowned in audience uproar, and the resulting journalistic battle resulted in a court case and a prison sentence for Satie, which, typically, he managed never to serve. The fact that Parade saw the unique meeting of the greatest artistic minds offered by Paris at that time was conveniently overlooked.

The first performance of “Parade” was drowned in audience uproar, and the resulting journalistic battle resulted in a court case and a prison sentence for Satie, which, typically, he managed never to serve. The fact that Parade saw the unique meeting of the greatest artistic minds offered by Paris at that time was conveniently overlooked.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Ballet “Parade” 1917