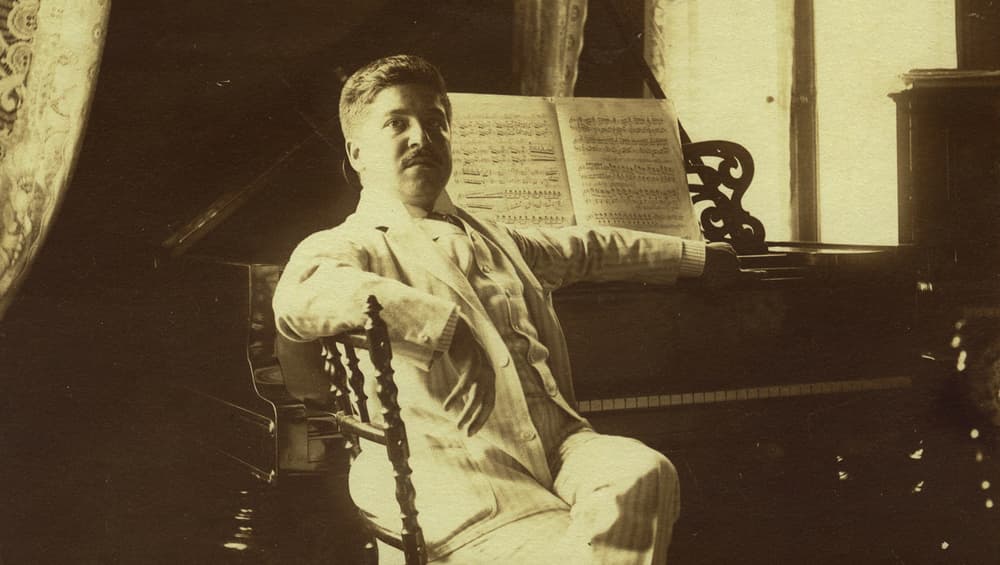

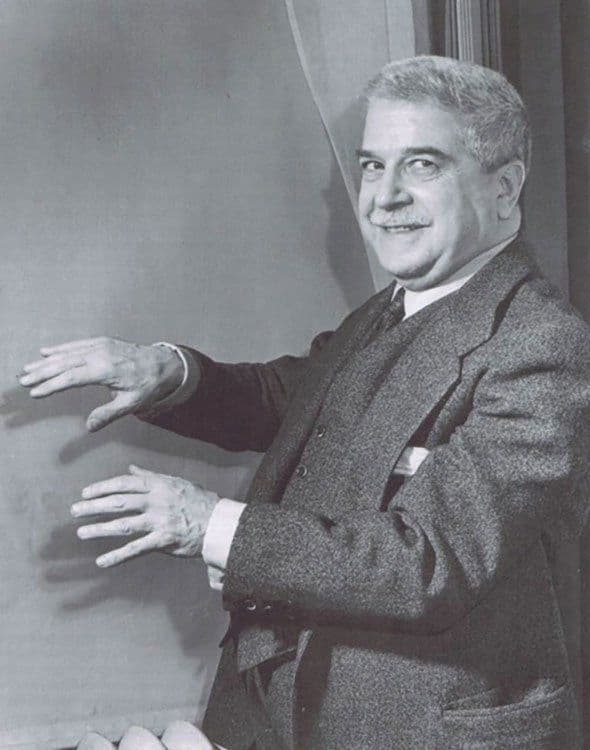

Pianist Artur Schnabel (1882-1951) is primarily associated with his glorious performances of the late Beethoven sonatas. As a scholar writes, “Here he often achieved a visionary quality in which the piano itself was almost forgotten; and although he allowed himself remarkable rhythmic freedom at times, his readings were still faithful to the composer’s intentions: to the spirit rather than to the letter. The truth is that in playing these great works his own imaginative world found its fullest expression.”

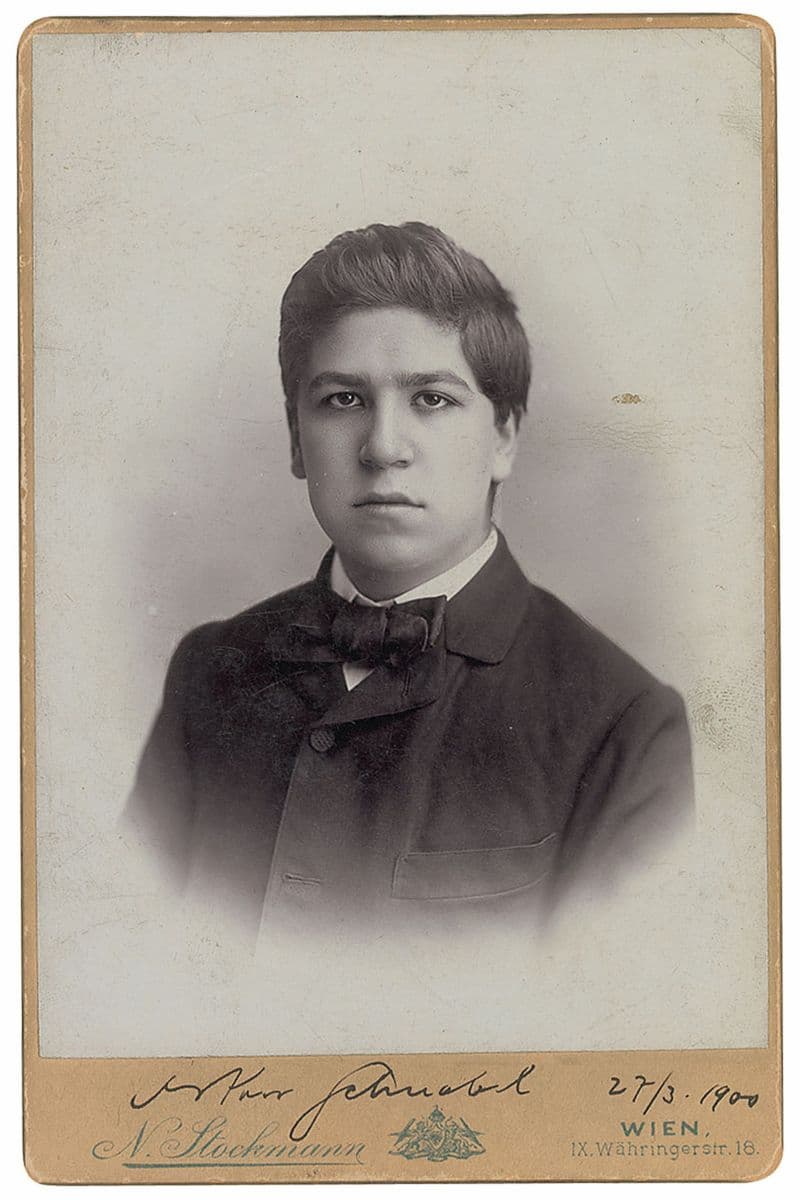

Artur Schnabel in 1900

Not to be outdone, his Schubert readings combine lyrical expression with a rhythmic élan and discipline that gave everything a new intensity. And in Mozart, he “achieved a perfection of phrasing, paired with his power of sustaining a long line without ever letting it become dull or lifeless.” Schnabel was known for his intellectual seriousness as a musician, always avoiding technical bravura. He never played encores, as he believed that they would cheapen the performance. As he once said, “I have always considered applause to be a receipt, not a bill.” The American composer Milton Babbitt famously said, “Schnabel was the thinking man’s pianist, and in spite of that was very popular.”

Artur Schnabel Plays Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 30, Op. 109

Schnabel was born on 17 April 1882 in the small town of Lipnik near Bielsko-Biała, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, today a part of Poland. “The little village was a curious place,” explained Schnabel. “My birthplace was tiny and rather poor, a suburb to a small town. The other town belonged to the Austrian province of Silesia. In Bielsko lived the so-called upper classes, and they were rather snooty we would say now. Biala, its twin, was more of an agricultural center. The people living in Lipnik, were apparently still poorer. I remember only one street; it was the whole place and the pride of it was the house of a liquor maker.”

Artur was the youngest of three children born to Isidor Schnabel, a textile merchant, and his wife Ernestine Taube (née Labin). Young Artur showed a remarkable aptitude for music, and his parents moved to Vienna in 1884 to support his talent. When his older sister Clara started taking piano lessons, Artur, without having lessons, succeeded in doing what she was taught much quicker than she. “I simply went to the piano and did it,” he recalls.

Artur Schnabel Plays Schubert’s Piano Sonata No. 21 in B-flat Major, D. 960 “Molto moderato”

“In 1889, when I was seven, I was taken to play for Professor Hans Schmidt, Professor at the Conservatory of the Society of Friends of Music, one of the most famous institutes in the world.” Schnabel remembered that Schmidt was the author of a thousand daily exercises, and he accepted him as a student. “My parents had decided that from my seventh year on, I was considered a professional musician. They had made me a pianist. I had no choice, as otherwise, I might have become a composer.”

Schnabel can’t remember what he learned from Schmidt, and he suggested that he might not have been a very inspiring teacher. He does remember, however, that a private concert was arranged for him by the time he turned eight years of age. “I played in a small hall connected with a piano showroom, and I played the D minor concerto by Mozart, still considered a work accessible chiefly to children—traditional misconceptions of this sort have an astonishing longevity. My concert must have been quite successful.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 22 in E-Flat Major, K. 482 (cadenzas by A. Schnabel) (Artur Schnabel, piano; New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Bruno Walter, cond.)

“When I was nine, somebody advised my mother that I should continue my studies with a certain Professor Leschetizky. He did not teach at a conservatory, and he had no official position. He lived rather aloofly and hardly appeared anywhere in public.” Leschetizky asked him to play his repertoire and then to sight-read.

“He opened, I remember, the piano score of Cavalleria Rusticana which had been published just a week before. My sight-reading must have satisfied him, for he accepted me as a student. The first year his wife, Madame Essipoff, a then famous piano virtuoso, actually took care of my pianism and he heard me only on a few occasions. Madame Essipoff was very kind to me. I had to play studies and exercises, chiefly Czerny’s, I remember. She used to put a coin on my hand, a silver coin almost as big as a silver dollar and if I played one Czerny study without dropping it, she gave it to me as a present.” Soon Leschetizky took over the instructions, and he said repeatedly to him in the presence of many other people, “You will never be a pianist. You are a musician.” As Schnabel recalled, “I did not make much of that statement and did not reflect much about it; even today I cannot quite grasp it.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Artur Schnabel Plays Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations, Op. 120

I cannot say what Schnabel’s recordings of the Schubert impromptus mean to me.