When famed conductor Otto Klemperer was roughly nine years of age, he encountered “the man who was to be the central inspiration of his entire life as a musician.” He remembers “seeing Mahler on the street when I was quite small. I was on my way to school. Without anyone pointing him out to me, I knew it was him. At that time he had a habit of pulling strange faces, which made a tremendous impression on me. I ran along shyly after him for about ten minutes and stared at him as though he were a deep-sea monster.”

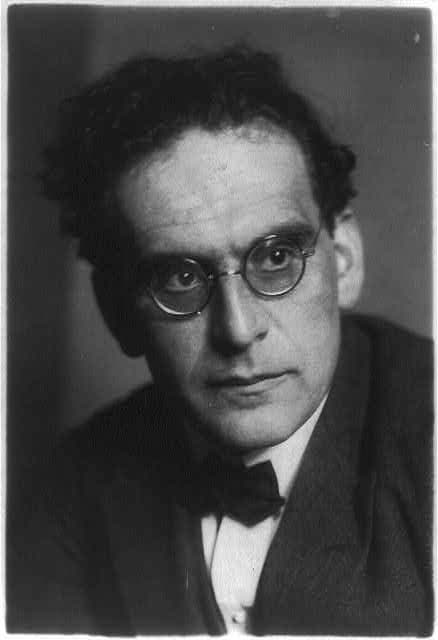

Otto Klemperer, c. 1920

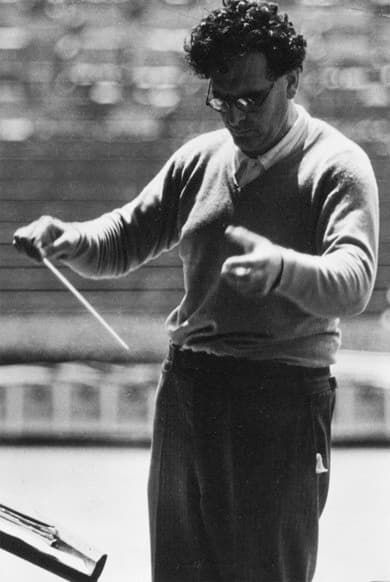

Klemperer formally met Mahler in Berlin in 1905, as he was rehearsing his Second Symphony. Klemperer was in charge of the off-stage orchestra, and he subsequently made a piano arrangement of the work. On a small calling card, Mahler wrote in 1907, “Gustav Mahler recommends Herr Klemperer as an outstanding musician, who despite his youth is already very experienced and is predestined for a conductor’s career. He vouches for the successful outcome of any probationary appointment and will gladly provide further information personally.” It was on the strength of Mahler’s recommendation that secured Klemperer’s appointment as chorus master and assistant conductor at the New German Theatre in Prague.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, “Resurrection” – V. Finale: Im Tempo des Scherzos (Ilona Steingruber, soprano; Hilde Rössel-Majdan, mezzo-soprano/alto; Vienna Academy Choir; Wiener Singverein; Vienna Symphony Orchestra; Otto Klemperer, cond.)

James Kwast

Otto Klemperer was born on 14 May 1885 in Breslau, the second child of Nathan Klemperer and his wife Ida, née Nathan. He grew up in a deeply Jewish religious household, but once the family moved to Hamburg they quickly assimilated into German society. As a biographer writes, “Otto Klemperer was brought up as a German citizen of Jewish faith, a halfway house that was to fail to withstand the storms of the twentieth century.” His mother Ida was a highly skilled pianist and composer of songs, and she regularly performed with a young violinist at home. Music was an integral part of the Klemperer household, and Otto decided early on that he wanted to be a musician or actor. He first took piano lessons from his mother at the age of five, and within one year, made rapid progress. Ida reports that her son’s “greatest pleasure was to put a book of poems on the piano and improvise on the ideas that these conjured up in his mind.” Blessed with perfect pitch, Otto was not only a promising pianist, but he seemingly had very definite opinions on how music should be performed.

Otto Klemperer Conducts Beethoven’s Symphony No. 8 (excerpt)

Ida Klemperer quickly recognized the exceptional abilities of her son and decided that Otto should have a professional teacher. As such, she engaged Hans Havekoss, a former organist and choirmaster from Mecklenburg. Otto studied with Havekoss for six years, “and quickly mastered much of the keyboard literature from Bach to Schumann.”

In terms of general education, Klemperer, by his own account was “a fairly undisciplined student,” and he subsequently lamented the shortcomings of his formal education. As a biographer writes, “as a result, he developed an almost exaggerated respect for learning and, as though in compensation for what he felt himself to lack, took special pleasure in the company of intellectuals.” In 1901, Klemperer was accepted at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, at that time the leading musical institution in Germany. He studied piano with James Kwast and theory with Ivan Knorr. Klemperer later explained, “To them, I owe the whole basis of my musical development.” Klemperer practiced the piano for eight hours a day and devoted a further hour to the violin and music theory. Unsurprisingly, his progress was rapid and within a couple of short months, he was chosen to perform at a conservatory concert.

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 4 in E-Flat Major, WAB 104, “Romantic” (1881 version, ed. R. Haas) (Vienna Symphony Orchestra; Otto Klemperer, cond.)

Kwast was forced to resign from Frankfurt because of a love affair with a student, and he took up a position at the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory in Berlin. “Klemperer and a number of other students decided to follow Kwast to Berlin,” and the press started to pay close attention to the emerging pianist.” Klemperer was well on his way to becoming a concert pianist, and he did enter a couple of competitions. However, as explained by his biographer Peter Heyworth, “nervousness hindered his progress. When performing in public, Klemperer’s hands grew wet with tension and his playing was considered to be less impressive than it was in private.”

When James Kwast moved to the Stern Conservatory in 1905, Klemperer once again followed him. While continuing his piano studies, he also joined Hans Pfitzner’s studio for conducting and composition. Under Pfitzner’s guidance and the influence of Brahms, Klemperer composed a piano trio that was publically performed. However, after his 1905 meeting with Mahler, it soon became clear that his career was moving in an entirely different direction.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Otto Klemperer Conducts Brahms’ Symphony No. 3, “Allegro con brio”