By the time Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) reached his 14th birthday, he already had an impressive variety and number of works in his compositional portfolio. In fact, between 1821 and 1823 alone, he composed a total of 12 symphonies for strings. With his parents belonging to the intellectual and financial elite of Berlin society, these compositions received their first performances at home concerts with the young Felix conducting. In the event, by 1824 he was ready to tackle a symphony written for full orchestra.

Felix Mendelssohn © U.S. Public Domain

Felix Mendelssohn: Symphony No.1 in C minor, Op. 11, “Allegro di molto” (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Roger Norrington, cond.)

It is truly astonishing that the teenage composer managed to quickly assemble a composition that skilfully synthesized Baroque techniques and Classical forms. Initially, he numbered the work “No. 13,” but it was immediately different from the previous twelve because the ensemble of strings was supplemented by woodwinds, brass, and timpani.

Always a quick learner, this work also integrated the latest contemporary orchestral techniques and symphonic processes. Orchestration had now become an essential factor in emphasising the characteristic quality of the music by means of differentiated timbres.

Felix Mendelssohn: Symphony No.1 in C minor, Op. 11, “Andante” (Tonkünstler Orchestra; Andrés Orozco-Estrada, cond.)

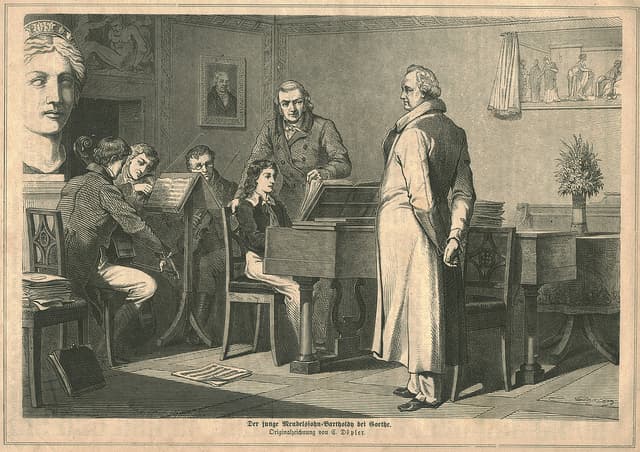

Felix Mendelssohn playing for Goethe

The C-minor Symphony was his first orchestral work to be published, and the original “No. 13” on the manuscript title page gave way to an official “No. 1” for publication. It privately sounded on 14 November 1824 in honour of his sister Fanny Mendelssohn’s 19th birthday. The public première occurred on 1 February 1827, with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra performing.

Mendelssohn’s first official symphony sparkles with the classical spirit of Mozart, while the symphonic fingerprints of Haydn and Beethoven forcefully emerge throughout the composition. It is a purely symphonic musical drama that also introduces us to the operatic world of Carl Maria von Weber. Just listen to the emotional and personal maturity the 15-year-old composer has to offer in the “Andante.” A sophisticated harmonic progression accompanies a simple yet highly personal theme. Decorated by imaginative woodwind ornamentations, this theme undergoes a series of variations and gradually accelerates via the syncopated rhythm taken from the string accompaniment.

Felix Mendelssohn: Symphony No.1 in C minor, Op. 11, “Menuetto: Allegro” (Japan Century Symphony Orchestra; Ryusuke Numajiri, cond.)

Both the “Minuet,” with its courtly syncopation, and the “Trio” providing a slow and ponderous contrast, represent an archaic return to the musical practices of the 18th century. Mendelssohn himself voiced reservations about this movement, and he found an ingenious solution when he took the work to London in May 1829.

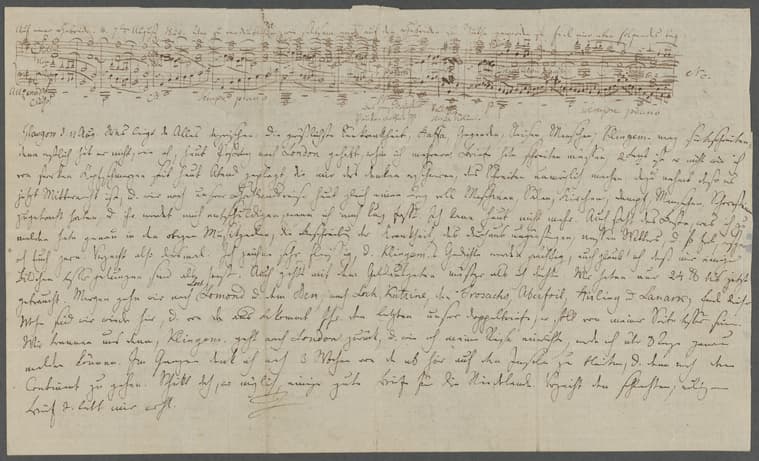

Mendelssohn’s letter, 1829

In a shrewd business move, he dedicated the symphony to the Philharmonic Society, and he personally took up the baton on May 25. Instead of the original Menuetto and Trio, however, Mendelssohn substituted his own orchestral enlargement of the “Scherzo” from the String Octet, a work he had composed in 1825, merely a year after the Symphony. Presenting his autograph copy of the revised score to the Society, London went on performing this particular version for the rest of the century. Mendelssohn, however, did restore the original third movement for publication in 1831.

Felix Mendelssohn: Octet in E-flat Major, Op. 20 “Scherzo (version for orchestra) (London Symphony Orchestra; John Eliot Gardiner, cond.)

In the event, the London reception was enthusiastic, and a contemporary critic wrote, “… though only about one or two-and-twenty years of age, he has already produced several works of magnitude, which, if at all to be compared with the present, ought, without such additional claim, to rank him among the first composers of the age.”

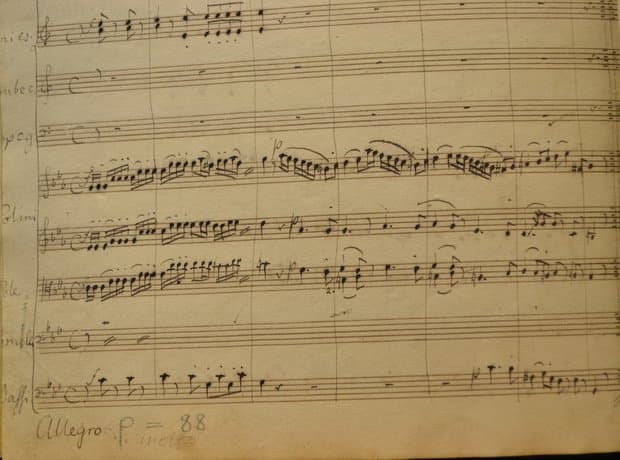

Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 1 in C minor – final movement

The concluding “Allegro” showcases a frenzied main theme, followed by a whimsical and extended pizzicato passage for strings. The strict fugal treatment in the development, which boisterously returns in the coda, provides a fitting and triumphant conclusion to Mendelssohn’s first serious foray into the symphonic genre. No wonder a contemporary critic wrote, “Fertility of invention and novelty of effect, are what first strike the hearers of M. Mendelssohn’s symphony; but at the same time, the melodiousness of its subjects, the vigour with which these are supported, the gracefulness of the slow movement, the playfulness of some parts, and the energy of others, are all felt.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter