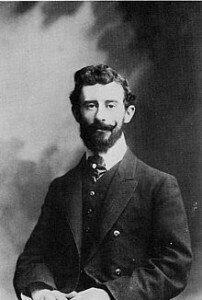

Photo of Maurice Ravel by Pierre Petit, 1907

There are many pieces of wonderful music that I’ve had the fortune to encounter, and still even more I’ve yet to come across. Making a list of ten of my favourites was nigh-on impossible, not least because the list would probably be completely different from one day to the next.

Some of these pieces hold a special significance for me because I played them or discovered them at significant moments in my life; others are just things I picked up along the way and held onto because of their brilliance.

Somehow, after much deliberation, I managed to whittle my seemingly endless list down to just ten pieces. I’ve cheated a little bit because some (ahem…most) of the works on this list are multi-movement, so I get a little more bang for my buck. My hope is that you perhaps discover something new, as well as seeing some more familiar faces present. Whatever your taste or experience, we all have music that we hold dear to us; here is a snapshot of mine.

Ravel: Daphnis and Chloe

“Daphnis and Chloe” by François Gérard

© Wikimedia

This was the first piece I wrote on my list, and it is music that changed my life when I discovered it at the age of 13. Based on an ancient Greek myth of the same title by Longus, it tells the story of Daphnis and Chloe, lovers who are separated when Chloe is abducted by pirates (spoiler alert: it turns out ok). My clarinet teacher recommended I listen to the second suite from this ballet – the entire ballet is just over an hour long, and Ravel extracted the 15-minute finale to form a concert suite – and right from the opening of this suite, with its mysterious, rippling chords, I was hooked.

I quickly sought out the other 45 minutes to this masterpiece, and still have never found an orchestral work that equals its variety of colour, imagination, and incredible harmony. Ok, so it can be a little on the schmaltzy side for Ravel, but it also has incredible grit and directness. Plus a wind machine. What’s not to like?

Ravel: Daphnis et Chloe (Radio France Choir; Radio France Philharmonic Orchestra; Myung-Whun Chung, cond.)

Debussy: La Mer

Again, this one was another life-changer. It’s hard to know at this point whether I just hear the sea in this music because I’ve known this piece for so long, or whether the volatile textures and lugubrious harmony really do conjure up images of waves, wind, and storms, but either way it’s an amazingly vivid and beautiful piece. Also a good one to introduce anyone you know who doesn’t know a lot of classical music to!

Stravinsky: Agon

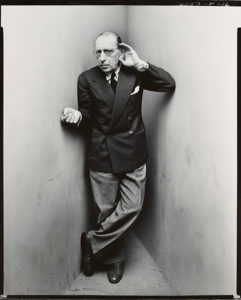

Photo of Igor Stravinsky, New York

April 22, 1948

© Condé Nast

In terms of Stravinsky ballets, it’s quite easy not to notice Agon in the shadow of the big three: The Firebird, Petrushka, and The Rite of Spring. However, if you dare to investigate the figure lurking in the background, you’ll find a totally quirky, fascinating piece of music.

Agon was finished in 1957, just as Stravinsky was turning away from Neoclassicism towards twelve-tone technique, and so in Agon you get this really bizarre collision of worlds. The ballet doesn’t even have a plot – it’s like the music is enough to tell a story, whatever it may be.

I could’ve chosen one of its famous cousins, but Agon holds a special place for me. The orchestra never plays a full tutti in the course of the whole piece, and Stravinsky creates groupings of instruments with totally unique sounds. The colours that the mandolin, harp and piano bring to the table are otherworldly but very effecting and incredibly human; in fact, that’s how I feel about this whole piece. It can seem very disjointed in places, but for me Agon is a melting pot bubbling away with endlessly curious, interesting noises.

Stravinsky: Agon (Boston Symphony Orchestra; Erich Leinsdorf, cond.)

Messiaen: Turangalîla-Symphonie

This is a real go-hard-or-go-home kind of piece. Scored for a giant orchestra, this ten-movement fiesta features, among many instruments, the very niche Ondes Martenot, and includes titles such as Joy of the Blood of the Stars. Fasten your seatbelts when you listen to this – you’ll probably come out the other side of it thinking something along the lines of ‘what the hell just happened?’ but for me, that’s kind of the point.

Messiaen: Turangalila-symphonie, I/29 (Howard Shelley, piano; Valerie Hartmann-Claverie, ondes martenot; BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Yan Pascal Tortelier, cond.)

Valentini: Sonata in G ‘Enharmonic’

This piece just makes me think of a time before the rules of harmony became solidified, when chords went to really unexpected places at the drop of a hat and didn’t have to be prepared or resolved in the same way. I listen to this music, particularly about two thirds of the way through when the opposing keys just cascade over each other, and wonder where we would have gone if harmony hadn’t changed in the way it did in Bach’s time (and onwards).

Richard Strauss: Four Last Songs

I discovered Strauss’ Four Last Songs as a teenager, and still am astounded by their emotional, tragic, depth. Written right at the end of his life, this collection of four songs for soprano and orchestra is devastatingly beautiful.

Mozart: Serenade for Winds ‘Gran Partita’

I never know whether it’s cheating to choose a piece with so many movements, but the Gran Partita is a towering work of the wind repertoire. There have been very few pieces since that showcases wind instruments in such a virtuosic – yet human – way. Featuring the ever-famous Adagio, you can also find a couple of charming minuets and a barnstorming finale to boot. It’s one of those pieces where you have as much fun playing it as you do simply listening to it.

Mozart: Serenade No. 10 in B-Flat Major, K. 361, “Gran Partita” (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Wind Ensemble; Karl Böhm, cond.)

Ravel: Le Tombeau de Couperin

I’m a sucker for Ravel – and although this collection of six short piano pieces couldn’t be further from his lavish Daphnis and Chloe, it still has his trademark style, poise and incisiveness. People often lump Debussy and Ravel together, but in my eyes, they are incredibly different composers. Ravel was obsessed with Mozart, with the classical ideals of balance and economy, and this really shines through in these movements, each one a tribute to a friend who died in World War One. The overall nature of the music is jolly and light – perhaps unusual for a work designed as a tribute to the dead – but, in Ravel’s words, ‘The dead are sad enough, in their eternal silence.’ Ravel orchestrated four of the six movements a couple of years after publishing the original piano score, and whichever version you listen to gives you a fresh insight into the mind of this seminal French composer.

Ravel: Le tombeau de Couperin (version for orchestra) (Radio France Philharmonic Orchestra; Myung-Whun Chung, cond.)

Ravel: Le tombeau de Couperin (version for piano) (Jean-Frédéric Neuburger, piano)

Bartók: Concerto for Orchestra

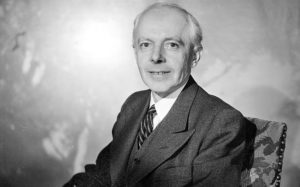

Béla Bartók, year 1939

© REX/Roger-Viollet

This just beat Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances to the post. Both are large-scale orchestral works, and both were written near the end of each composer’s life, but apart from that, they’re pretty chalk-and-cheese. What attracted me to the Bartók was its intensity and delicacy, its raw, blistering harmonies that rub shoulders with pure sensuality. From the detached, eccentric second movement, to the fireworks of the finale, this piece sweeps a whole palette of orchestral colours before you, exposing you to sounds you may never have heard an orchestra make before.

Bartók: Concerto for Orchestra, BB 123 (Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra; Zoltán Kocsis, cond.)

Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

Oh, come on. I know, I know, so predictable to end with a crowd-pleaser… but just let me have this one, please? I know I’m biased as a clarinettist, but it is (in my humble opinion) one of the most amazing works not just of the clarinet repertoire, but of Mozart’s entire output.