In his 2009 recording, American composer B.R. Pearson presents us with a journey around in his Paintings in the Hall. In his view, both art and music work together to divide space and time. Paintings are space and music is time. This is the old ‘particles versus waves’ argument, but now in art, not science.

As much as one cannot ‘hear’ a painting, one cannot really ‘see’ music – one’s for looking and the other for hearing but, at the same time, they realise many of the same goals. In the composer’s words, ‘They chronicle emotions, events, movement, stagnation, imagination, technique, colour, beauty, realism, and abstraction. They obfuscate, resonate, irritate, ameliorate, imitate, give humanity cause to congregate. They’re revered and despised with our ears and our eyes’. Pearson’s goal in his set of pieces is to complete the paintings through music. To give the space some time to resonate. ‘To see them with our ears’.

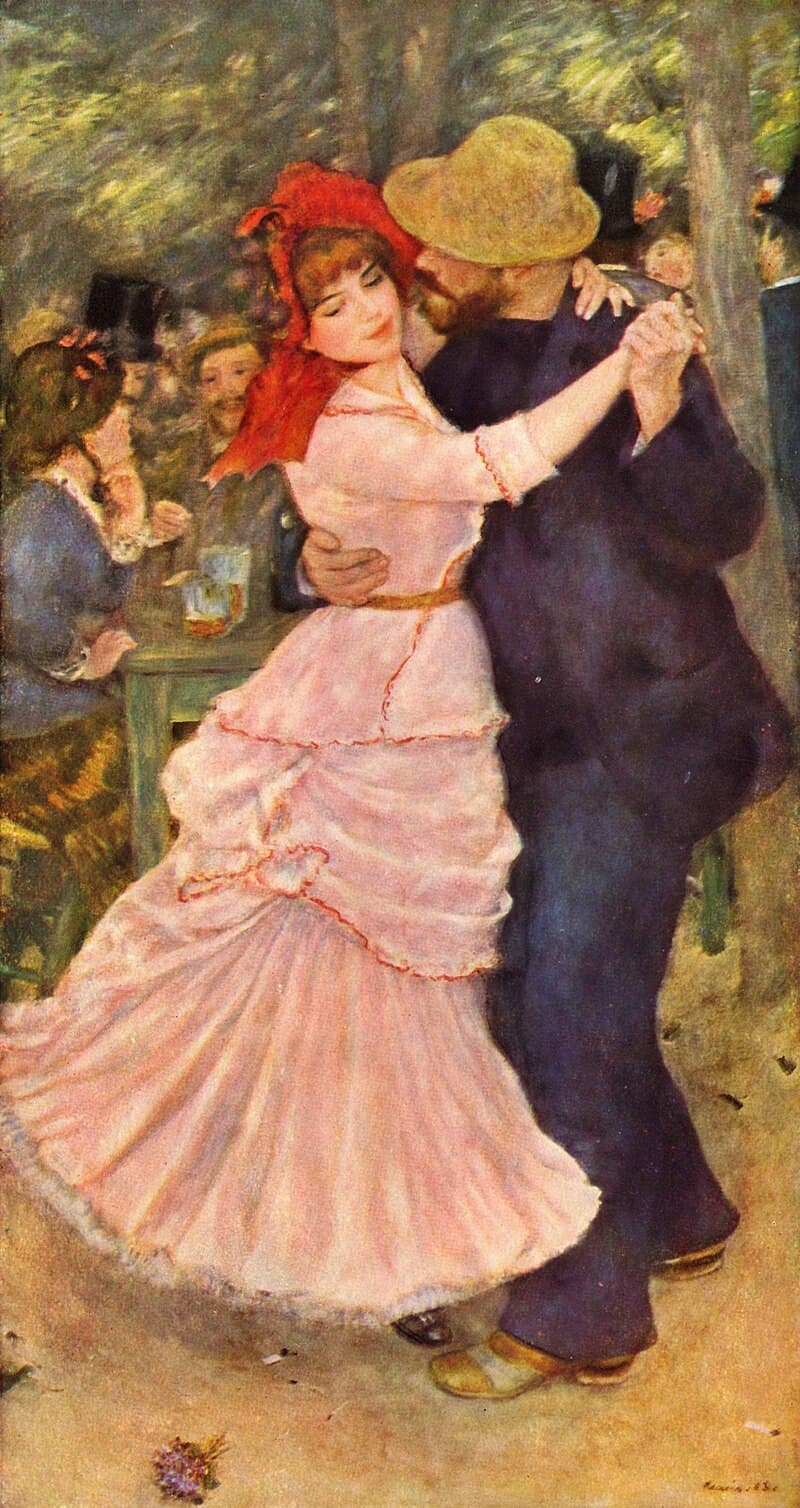

His art survey goes from the grand masters of Impressionism to the grand masters of modernism. He starts with Renoir’s Dance at Bougival, where a man in a dark suit dances with a woman in pink. The couple stands still in the midst of a background that seems in motion. (For more on this painting and the music, see Musicians and Artists: Pearson and Renoir.

B.R. Pearson: Dance at Bougival (Renoir) (B.R. Pearson, piano)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir: Dance at Bougival, 1883 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts)

Jumping forward 80 years, we encounter Women III by the Dutch-American abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning. This is part of his ‘Woman’ series, which began in 1950 and finished in 1953 with Woman VI.

de Kooning: Woman III, 1953 (collection of Steven A. Cohen)

Woman III pays homage to many of Picasso’s women. The palette is muted greys and whites with black arcs to outline the body. The curves define her chest and arms, while her legs are much smaller.

B.R. Pearson: Woman III (de Kooning) (B.R. Pearson, piano)

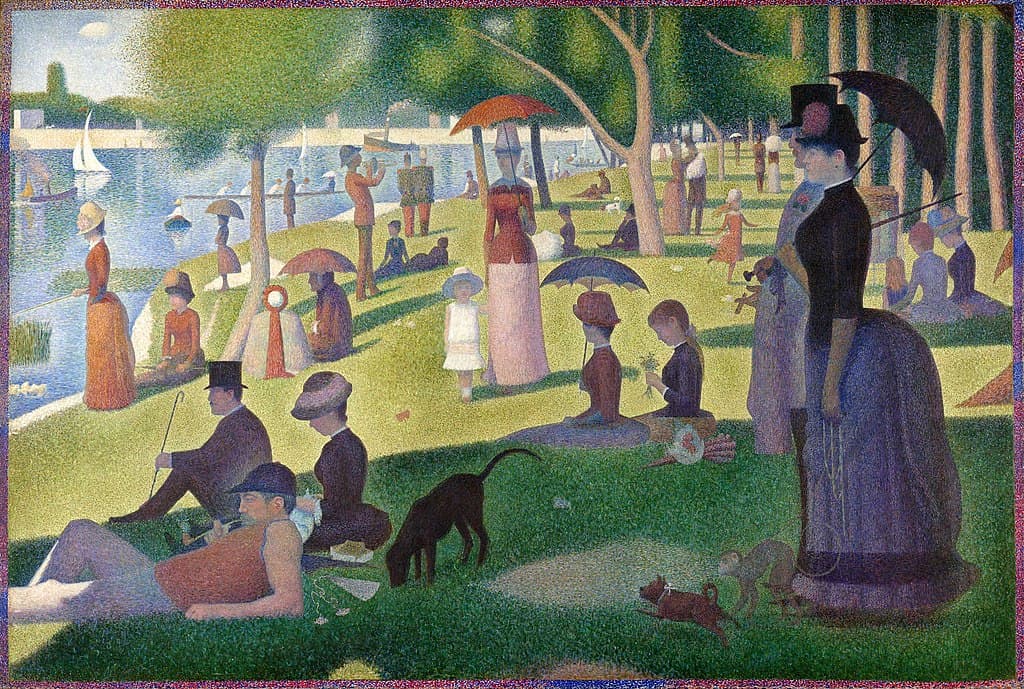

Jumping back in time to one of the largest impressionist paintings, Pearson next examines Seurat’s pointillist masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

Seurat: A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1886 (Art Institute of Chicago)

Although you might expect a pointillist style in the music, Pearson seems to be connecting the dots for us in a flowing presentation of a Sunday out in the sunshine.

B.R. Pearson: Sunday Afternoon on the Island La Grande Jatte (Seurat) (B.R. Pearson, piano)

Wassily Kandinsky’s 1913 painting, Composition VII, is pure expressionism. Art scholars believe that ‘the work is a combination of the themes of Resurrection, Judgment Day, the Flood and the Garden of Eden’. Kandinsky started work on this painting with an abstract watercolour, Untitled (Study for Composition VII, Première abstraction).

Kandinsky: Untitled (Study for Composition VII, Première abstraction), 1913 (Paris: Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou)

When he committed it to painting later in the year, the basic forms and ideas in the watercolour were filled out and augmented. This was Kandinsky’s first movement away from the representational that had characterised Western art for centuries. It was the first purely abstract work that came to define the field.

Vassily Kandinsky: Composition VII, 1913 (Moscow: Tretyakov Gallery)

Pearson’s music uses recurring tones to convey an abstract idea. The pitch is the same, but as the context around it changes, we see/hear the pitch differently.

B.R. Pearson: Composition VII (Kandinsky) (B.R. Pearson, piano)

The Girl with the Pearl Earring is only the most recent of the many names for this portrait piece. It may have started life as a work ‘painted in the Turkish fashion’. It was called a ‘trony’, i.e., a portrait that was also a study of expression. It appeared in a 1696 sale as Een Tronie in Antique Klederen, ongemeen konstig (Portrait in Antique Costume, uncommonly artistic). When it was given to the Mauritshuis in 1902, it was called Meisje met tulband (Girl with a Turban). It wasn’t until 1995 that the title Meisje met de parel (Girl with a Pearl) was given to the painting. In English, the painting was known simply as Head of a Young Girl or The Pearl.

Vermeer: Girl with the Pearl Earring, ca 1665 (The Hague, Mauritshuis)

Pearson’s Girl is a setting of solemnity and balance. The music isn’t of the mid-17th century but rather a modern musing on the image.

B.R. Pearson: Girl with the Pearl Earring (Vermeer) (B.R. Pearson, piano)

Édouard Manet’s 1864 painting The Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama commemorates the battle between American and Confederate forces on 19 July 1864 that took place off the coast of France at Cherbourg. The sea battle, where the American forces defeated the Confederate raider, was visible from the coast. Manet was not present; he based his painting on descriptions in the newspaper following the battle. Just 26 days after the battle, Manet’s painting was on exhibition in Paris. In the picture, the Alabama is at the centre, sinking; the Kearsage is at the back left, hidden in smoke and flying an American flag. At the back right is the Deerhound, a British yacht that picked up survivors and, evading the American boats, took the rescued Confederate sailors, including Alabama’s Captain Semmes, and took them to safety in Southampton. The boat in the foreground is a French ship also rescuing sailors from the water, as in the middle of the painting. One element of the painting that was thought to have come from his study of Japanese prints is the high horizon, which makes most of the painting of the sea.

Manet: The Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama,1864 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Pearson’s Battle seems to put us in the water with the sailors hoping for rescue. The sound flows around us, but not with cannon and fire, but more liquid and, perhaps, more dangerous.

B.R. Pearson: The Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama (Manet) (B.R. Pearson, piano)

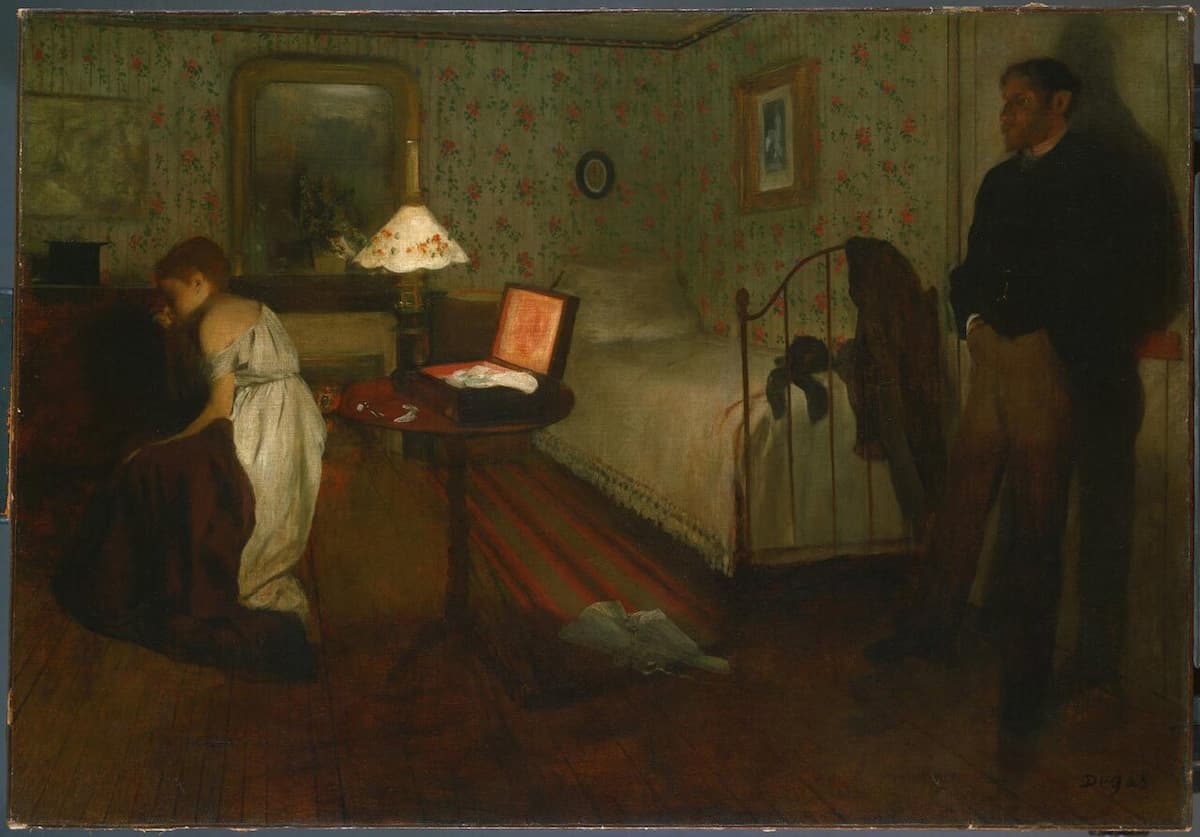

A highly theatrical painting by Edgar Degas, Intérior (Interior), or Le Viol (The Rape), uses shadows and dramatic lighting in a way unique to his works. Degas referred to the work as ‘mon tableau de genre’ (my genre painting), and although it was painted in 1899, it wasn’t exhibited until 1905. A number of different literary sources have been suggested for the subject, but none fit the scene exactly. The clothing on the floor and the blood on the bed seem to indicate a violent encounter.

Degas: Intérior / Le Viol (The Rape), 1869 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Pearson seems to give a very surface reading of what is regarded as an uncharacteristic painting by Degas. He seems to read the woman’s position and the light as more relaxed than most art historians.

B.R. Pearson: Le Viol (Degas) (B.R. Pearson, piano)

Pablo Picasso’s 1937 anti-war painting Guernica is enormous (3.49 meters (11 ft 5 in) tall and 7.76 meters (25 ft 6 in) across), larger even than Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (2.07 m (6 ft 9 inches) tall and 3.081 m (10 ft 1 in) across). Picasso was reacting to the German bombing of the Basque town of Guernica on 26 April 1937 and created what has been called ‘the most moving and powerful anti-war painting in history. The painting captures the chaos and tragedy of the event, from dead children, frightened and screaming animals, and people everywhere, unable to leave the debacle because all the bridges of the town had already been destroyed. It didn’t need colour – it was painted in black and white – to make its effective point.

Picasso: Guernica, 1937 (Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain)

Pearson picks his way through the imagery, sometimes with light, hesitant steps, and other times with heavy, pulsing rushes.

B.R. Pearson: Guernica (Picasso) (B.R. Pearson, piano)

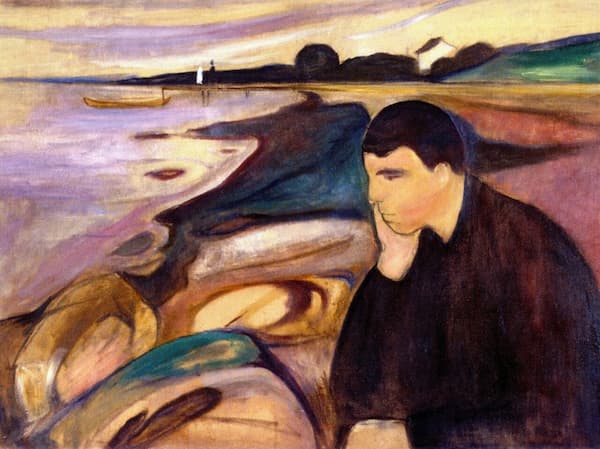

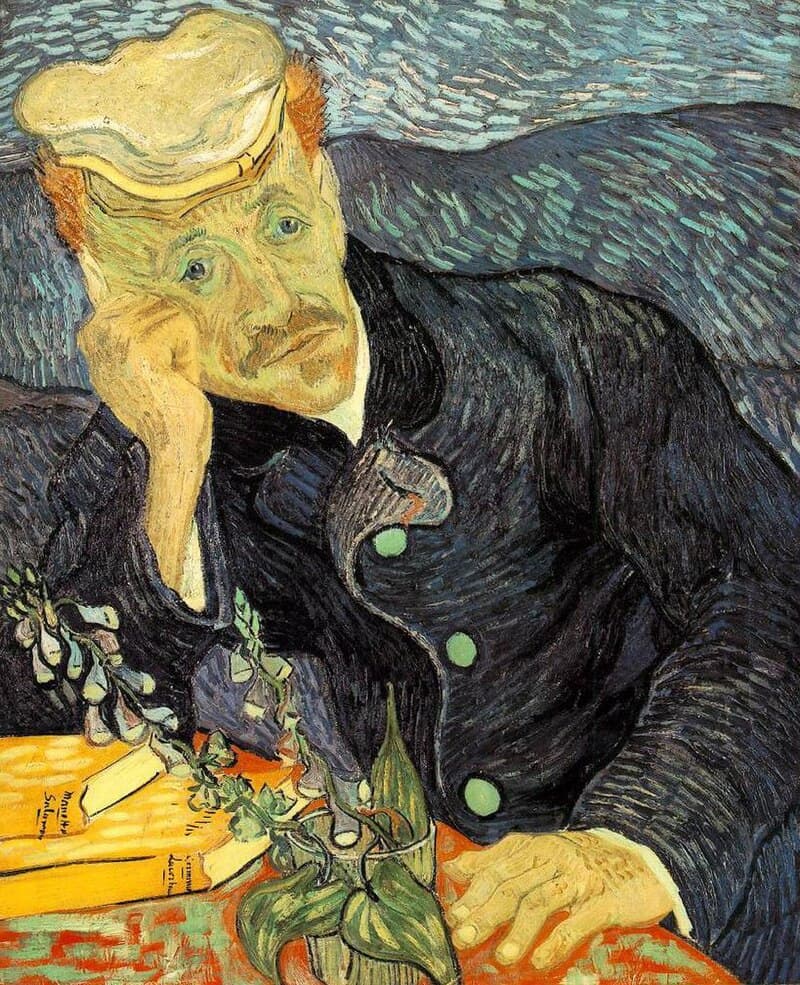

Vincent van Gogh’s portrait of the homoeopathic doctor Paul Gachet, with whom Van Gogh stayed in 1890 upon his release from the asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. His brother Theo found Gauchet through the artist Camille Pissarro. Pissarro was a former patient of the doctor and recommended him to Theo. Although Vincent first didn’t like Gachet, he soon found a ‘true friend’ in him. While Gauchet took care of van Gogh in the last three months of his life (May 1890 until his suicide on 29 July 1890), van Gogh had one of the most creative periods of his life, painting some 70 works. Van Gogh painted two versions, both of which show the doctor resting his head on his right hand, leaning on a red-covered table. The first has a primarily green background.

Van Gogh: Portrait of Dr. Gachet,1890 (private collection)

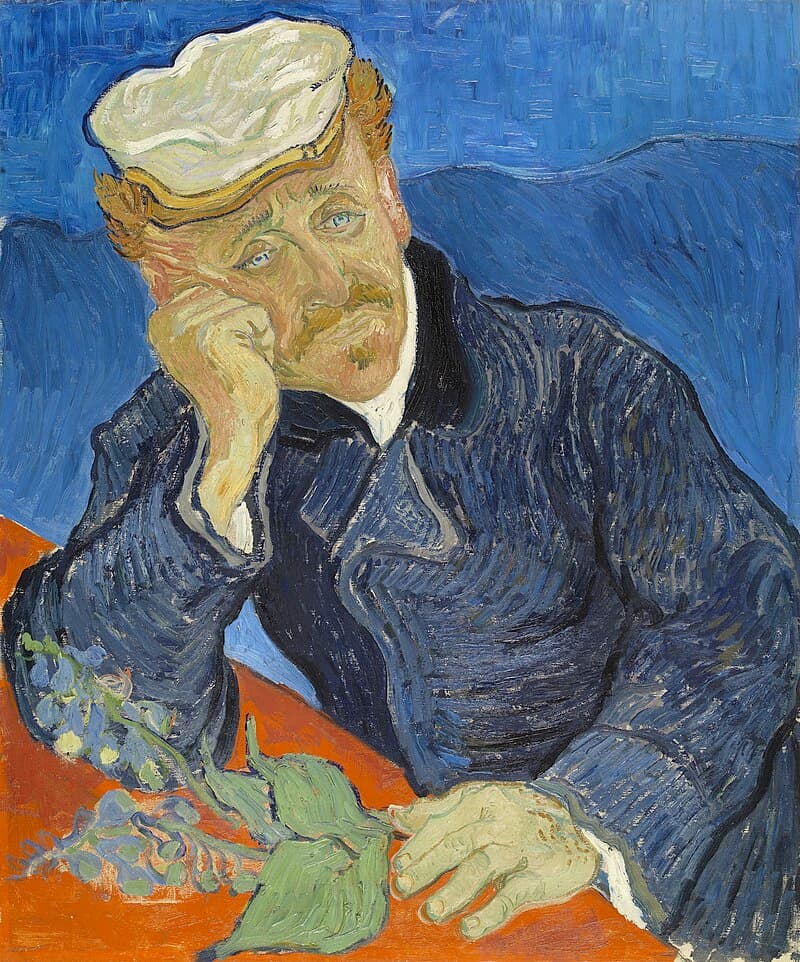

And the second a blue background.

Van Gogh: Portrait of Dr. Gachet,1890 (Paris: Musée d’Orsay)

The two works were completed six weeks before van Gogh shot himself, dying of his wounds three days later.

The tiredness and melancholy of the painting come through in Pearson’s quiet work.

B.R. Pearson: Dr. Gachet (van Gogh) (B.R. Pearson, piano)

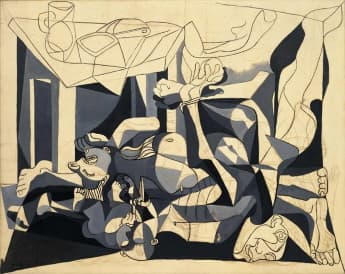

The last picture is another Picasso, The Charnel House. It was begun in 1944, seven years after Guernica and was left unfinished. Composed while Picasso lived in Paris under German occupation, it is another of his three major anti-war pieces (Guernica, The Charnel House, and Massacre in Korea (1951)).

Picasso depicted life under German occupation as dark and grey. The subject is a Spanish Republican family who had been killed in their kitchen. The figures, a woman, a man, and a boy, are shown in contorted positions, all underneath their kitchen table, with dinner prepared and waiting. Seen at the back of the painting is a door that will offer no escape.

Although the painting was incomplete, Picasso was satisfied enough with it to donate it to the National Association of Veterans of the Resistance in 1946. He asked for it back in 1946 to make some alterations and kept the painting until 1954, when it was sold to an American collector. Picasso’s name for the work was The Massacre, but once it became known as The Charnel House, he adopted that name. William Rubin, director of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, bought the piece for the museum and saw it as the completion of Guernica – if one was the start of the war, The Charnel House was how it would end.

Picasso: The Charnel House,1945 (New York: Museum of Modern Art)

Pearson starts us low in the painting, with low pitches and drooping melodies, almost like dripping blood.

B.R. Pearson: The Charnel House (Picasso) (B.R. Pearson, piano)

Although he started his recording with images of women, Pearson’s picture collection, by picture 6, becomes pictures of violence, war, and its aftermath. The relatively bloodless battle picture by Manet starts us down this path to death, and even Dr Gachet’s portrait, done in van Gogh’s last months, carries a certain melancholic feeling.

This isn’t a modern Pictures at an Exhibition, Mussorgsky’s tour through Viktor Hartmann’s work. It’s not one artist’s work but work by many artists spanning almost 300 years of work (1665 to 1953). In his attempt to bring time to the space that pictures occupy, Pearson has avoided the obvious – this isn’t program music but rather music for the space within an image. The various interpretations one might have of an image can be found in the music.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter