In 1498, in response to the announcement of the end of the world that the European Christian world believed would happen in 1500, the 27-year-old Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) completed his sixteen designs for the Apokalyse (Apocalypse).

Dürer: Self-portrait age 26, 1497 (Prado Museum)

Dürer was born in Nurnberg, the third of his parent’s 18 children, His father was a successful goldsmith and his godfather, Anton Koberger, was one of the most successful publishers in Germany, responsible for the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493) that the young Dürer may have worked on.

Although his father wanted him to apprentice with him as a goldsmith, his skills as an artist were recognized while he was still in his early teens and he apprenticed to Michel Wolgemut, the leading artist in Nuremberg, at age 15. After he completed his apprenticeship in 1490, he set off on his traditional Wanderjahre, to learn skills from artists elsewhere. In his 4-year ‘gap year’, Dürer travelled around Northern Europe, working with engravers in Colmar, Frankfurt, The Netherlands, Strasbourg, and Basel before returning to Nuremberg to be married. He next travelled to Italy, visiting Venice, Padua, and Mantua, and learning about new engraving techniques and new art styles.

Upon returning to Nuremberg in 1495, he immediately showed his Italian influence by creating larger and more finely cut prints than were normally seen in Germany. The 1498 series on the Apocalypse was based on scenes from The Book of Revelation, which forms the final book of the Christian Bible. In the book, a prophet named John describes a series of prophetic visions that include figures such as the Seven-Headed Dragon, the Serpent, and the Beast. The latter rises ‘up out of the sea, having seven heads and ten horns, and upon his horns ten crowns’.

The book was published with an image on one side of a page and text from Revelation printed on the other side. The text was printed by Anton Koberger. The woodcuts for the images would have been created by Dürer on paper. The paper would have been placed face-down on a block of wood and the block cutter (formschneider) would have carved away the wood not needed in the image, leaving a flat surface that would carry ink and would print on the page. Dürer’s original art was destroyed in the carving process.

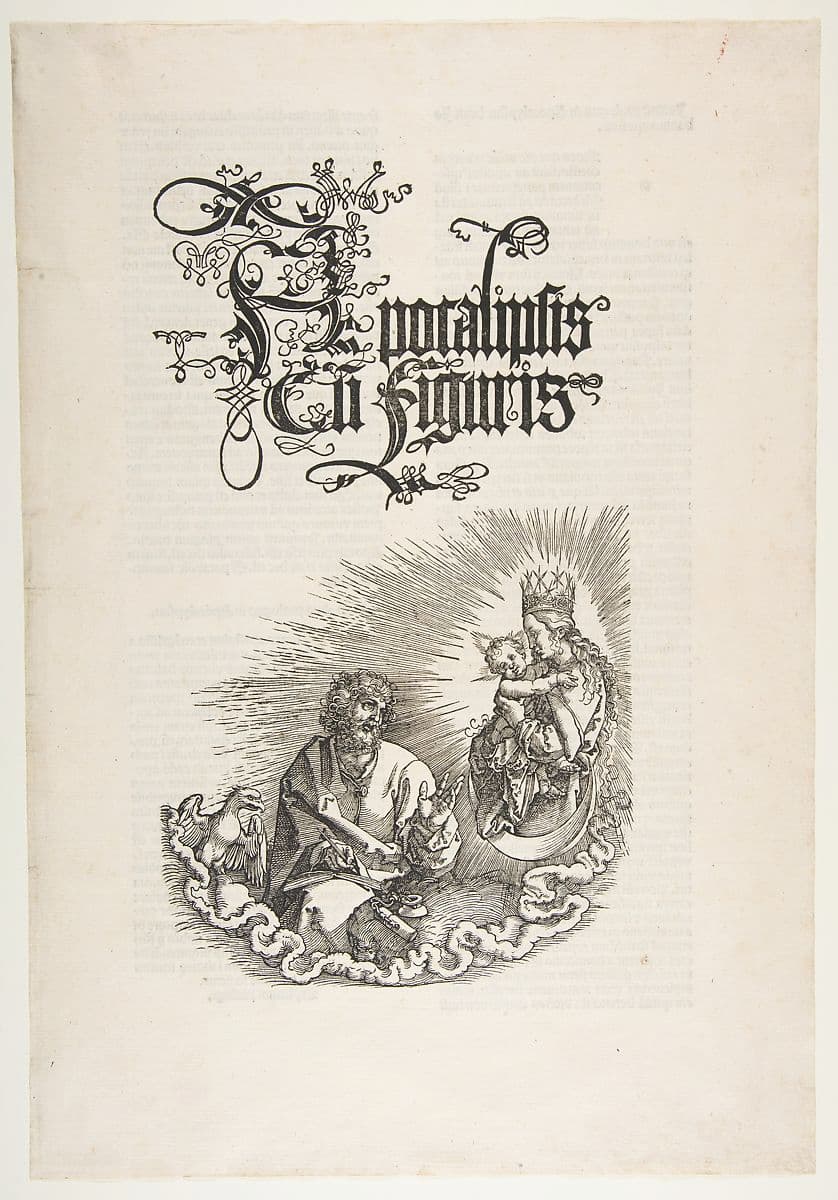

The book begins with a cover image of Mary appearing to St. John. Here she’s shown as the Woman with the Moon. This image was added to the original 15 for the 1511 edition.

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris, 1511 (Met Museum)

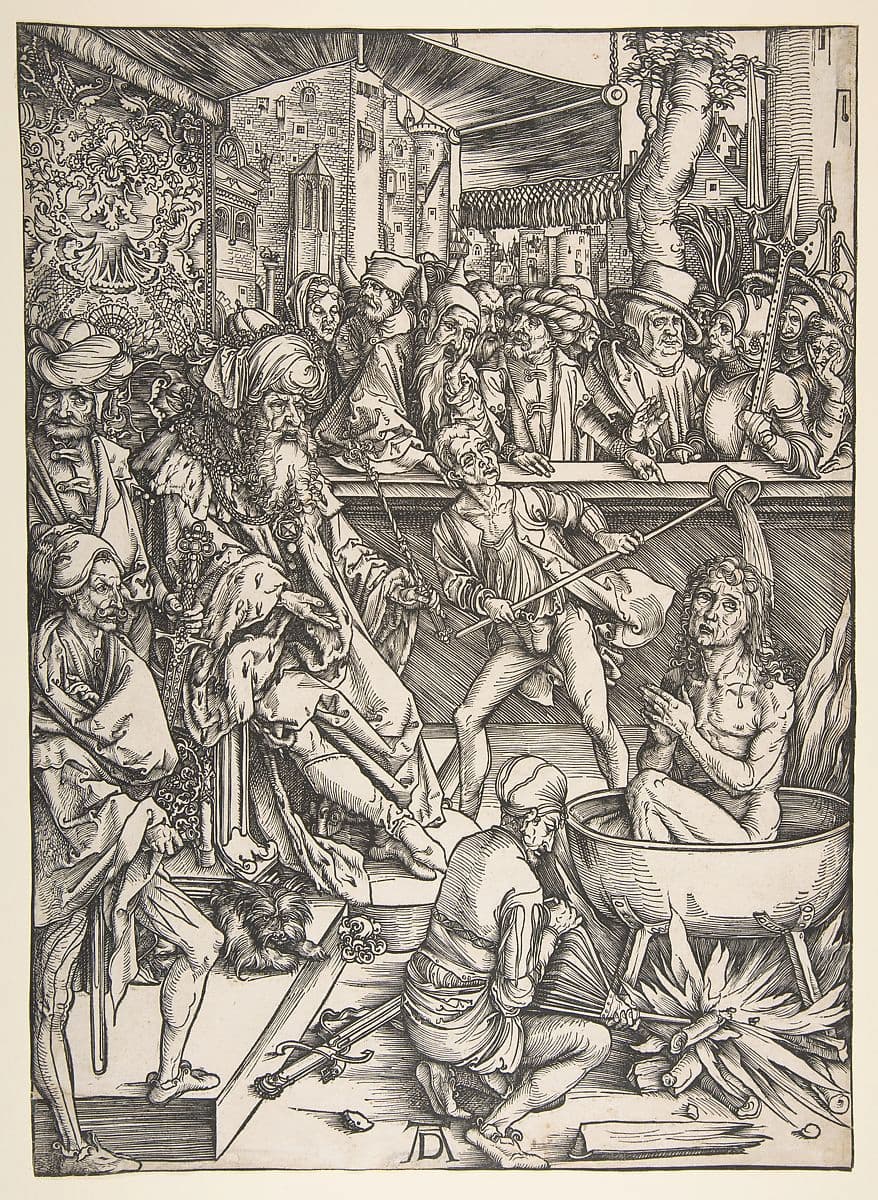

First in the book proper is The martyrdom of St John, shown in a pot of boiling oil while more oil is poured on him from above.

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 1. The Martyrdom of St. John, 1498

St John’s vision of the seven candlesticks comes from Revelation 1/11.

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 2. St John’s vision of the seven candlesticks, 1498

St John kneeling before Christ and the twenty-four elders comes from Revelation 4/4.

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 3. St John kneeling before Christ and the twenty-four elders, 1498

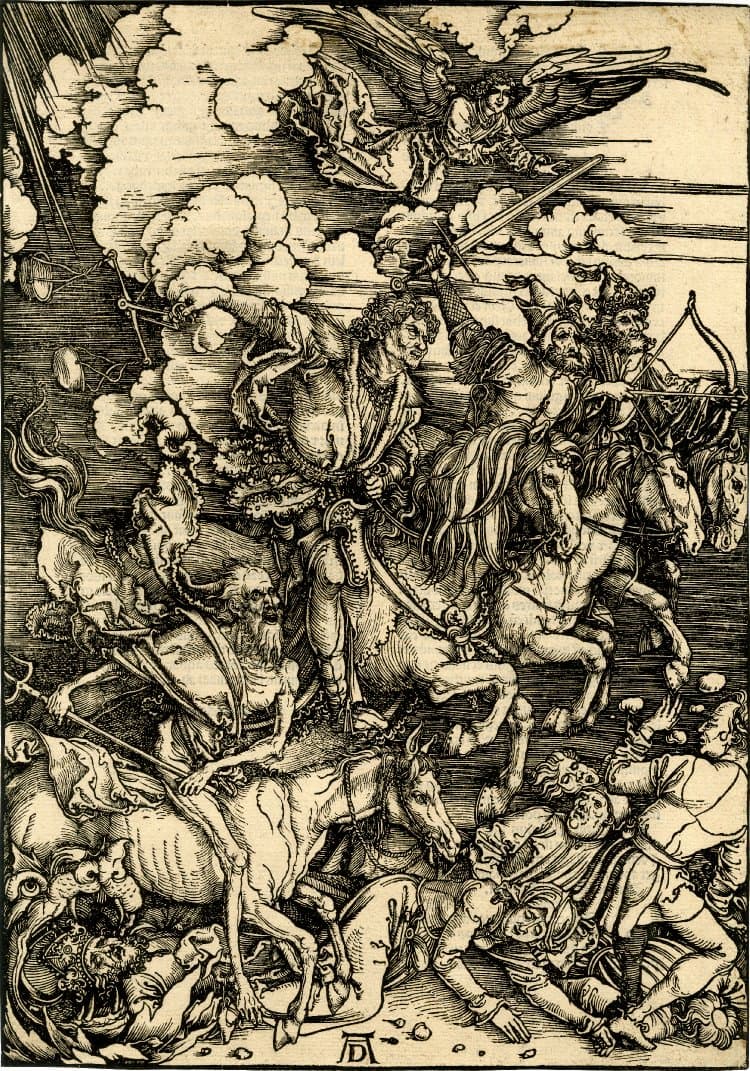

One of the most famous of the Dürer prints from this collection is the image of The four horsemen of the Apocalypse (Revelation 6:1-8). Although in the original text, each horse is a distinctive colour: White, Red, Black, Pale, Dürer, working only in black and white with grey differentiates the riders by the attributes that they carry: Death has a trident, Famine carries a balance, War has a sword, and Plague carries a bow. Up to this point, most depictions of the four horsemen were rather staid, Dürer, however, injects motion and a dangerous intent into the image. The horses overlap and the eye is carried upward through the image to the bright upper right corner. Along the bottom, everyone is trampled, starting with the crowned figure in the bottom left corner who is being eaten by a dragon.

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 4. The four horsemen of the Apocalypse, 1498

The four horsemen were the first four seals. The next image, The opening of the fifth and sixth seals (Revelation 6:9-17), brings the altar where those who were killed for their religious beliefs call for justice, and with the opening of the sixth seal, a great earthquake and the stars falling to earth.

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 5. The opening of the fifth and sixth seals, 1498

Angels hold back the four winds while the elect are marked as the servants of God (Revelation 7:1-13)

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 6. Four angels holding back the winds, and the marking of the elect, 1498

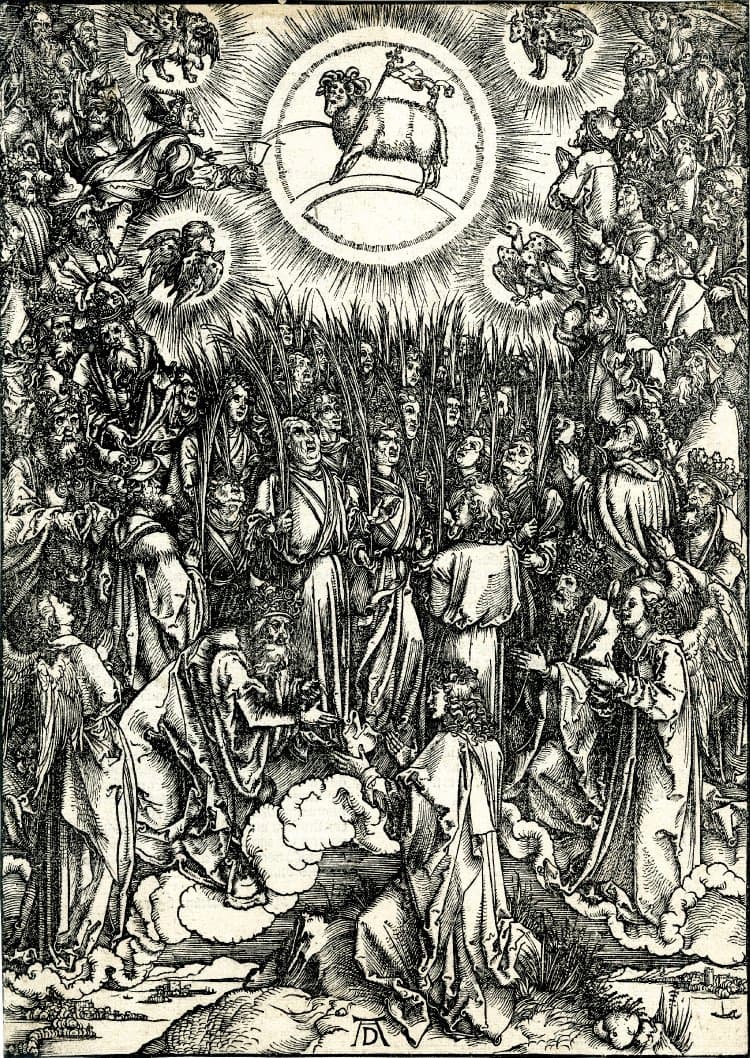

Next follows The hymn in adoration of the lamb sung by those who, clothed in white, are brought to salvation by the lamb (Revelation 7:13-17)

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 7. The hymn in adoration of the lamb, 1498

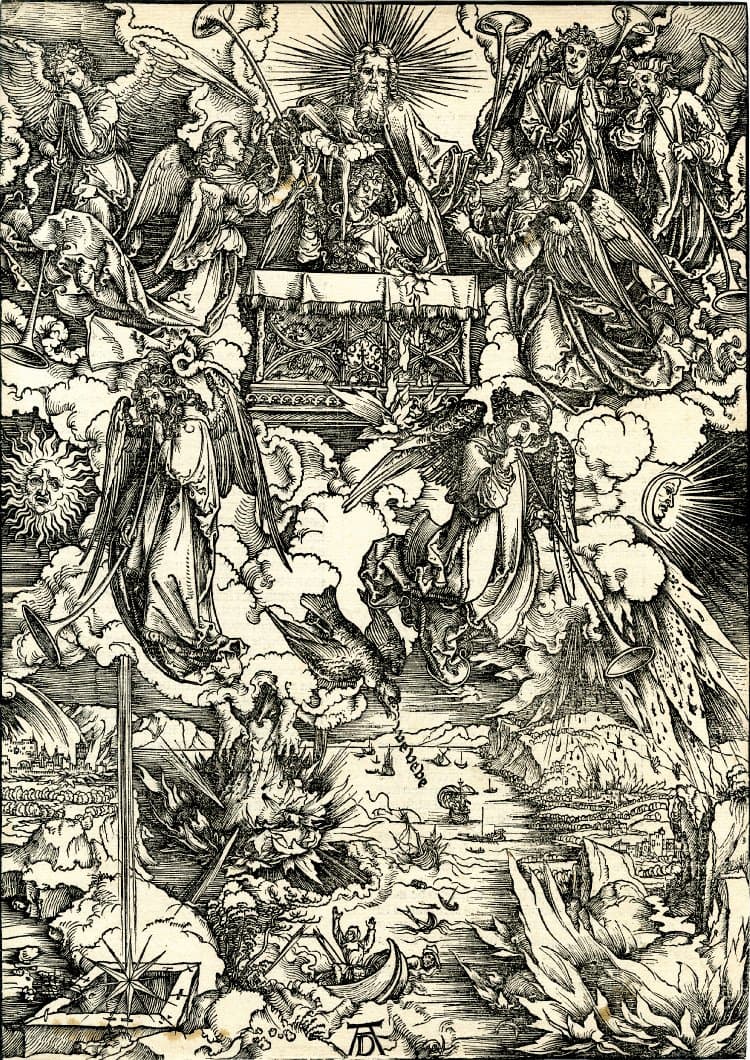

At the opening of the seventh seal, the seven angels appear and destruction is visited upon the earth: creatures die, ships sink, water becomes poison, the sky darkens, and an eagle cries ‘woe … to the inhabitants of the earth….’

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 8. The opening of the seventh seal and the eagle crying ‘Woe’n, 1498

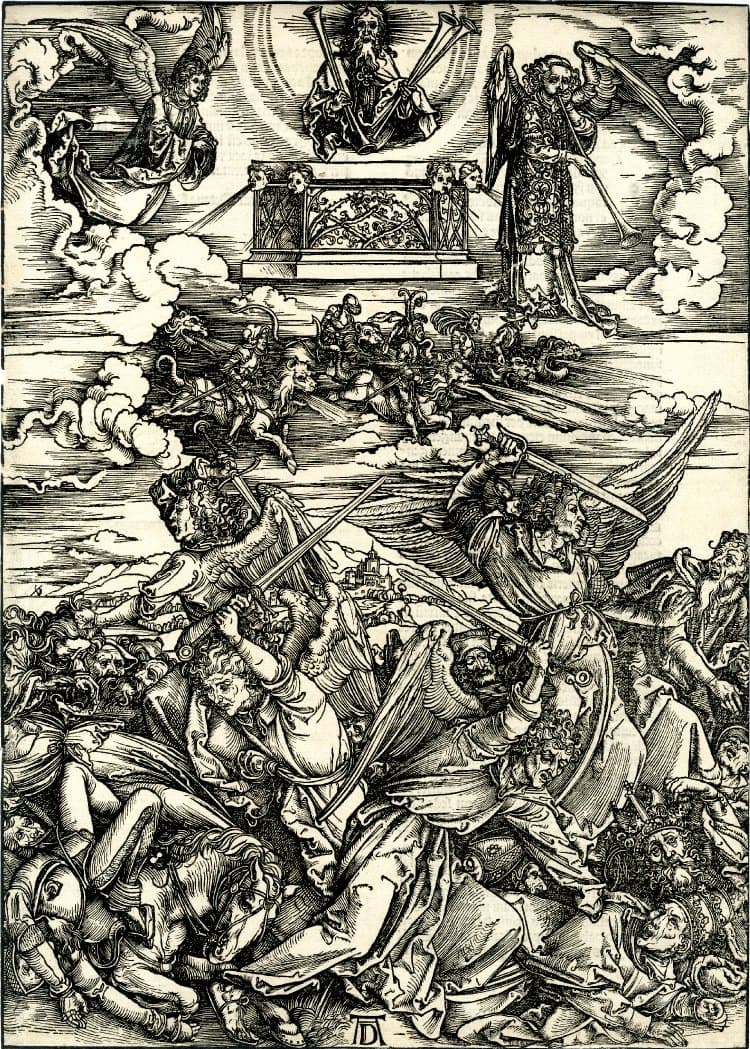

The four angels of Death appear and wreak havoc (Revelation 9). Those falling to the angels’ swords come from all walks of life: kings to commoners.

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 9. The four angels of Death, 1498

In Revelation 10:8-10, the narrator, John, is told to take a book from an angel who stands upon the sea and the earth (here shown as 2 burning columns) and eat it – it will be bitter in his belly, but sweet as honey in his mouth.

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 10. St John eating the book, 1498

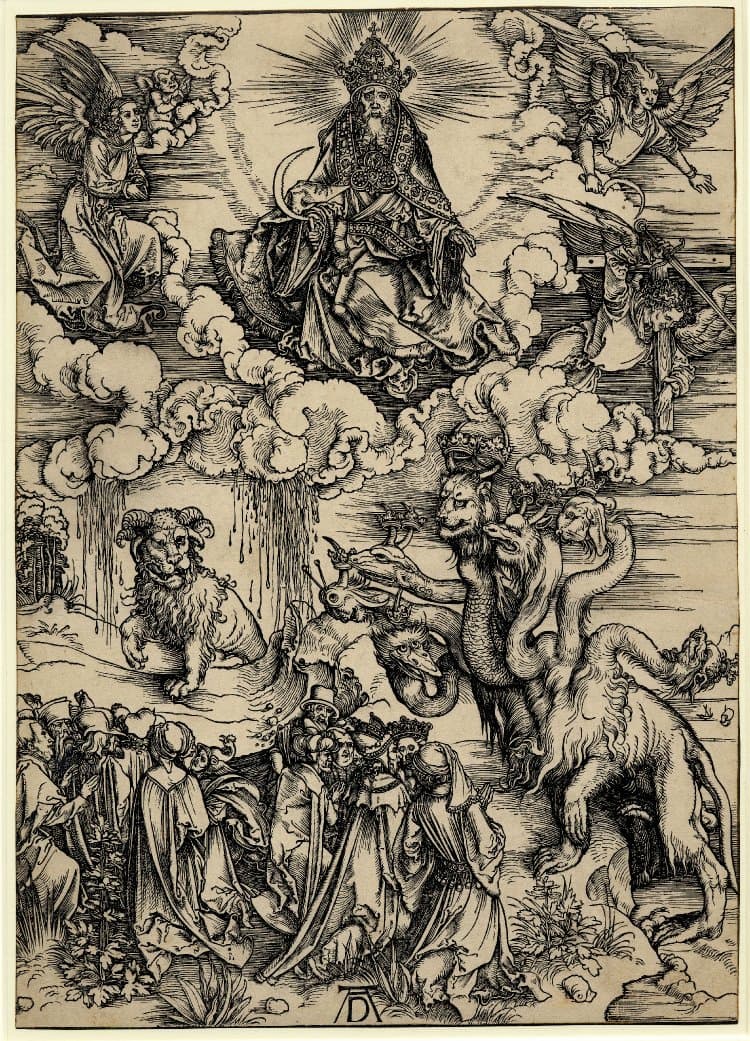

Revelation 10:1-4 brings us a pregnant woman ‘clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars’. A 7-headed dragon waits to devour her yet-unborn child while the Archangel Michael prepares to defend her.

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 11. The woman of the Apocalypse and the seven-headed dragon, 1498

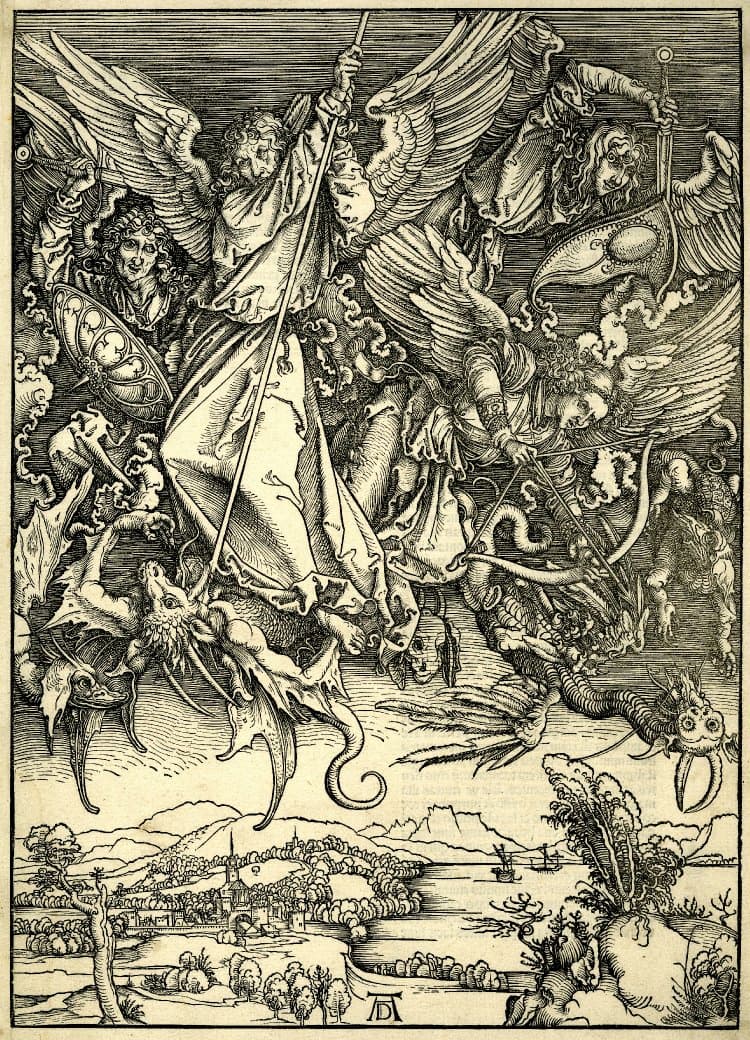

Michael and his angels (Revelation 10:7-9) fight the great dragon and defeat him.

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 12. Saint Michael Fighting the Dragon, 1498

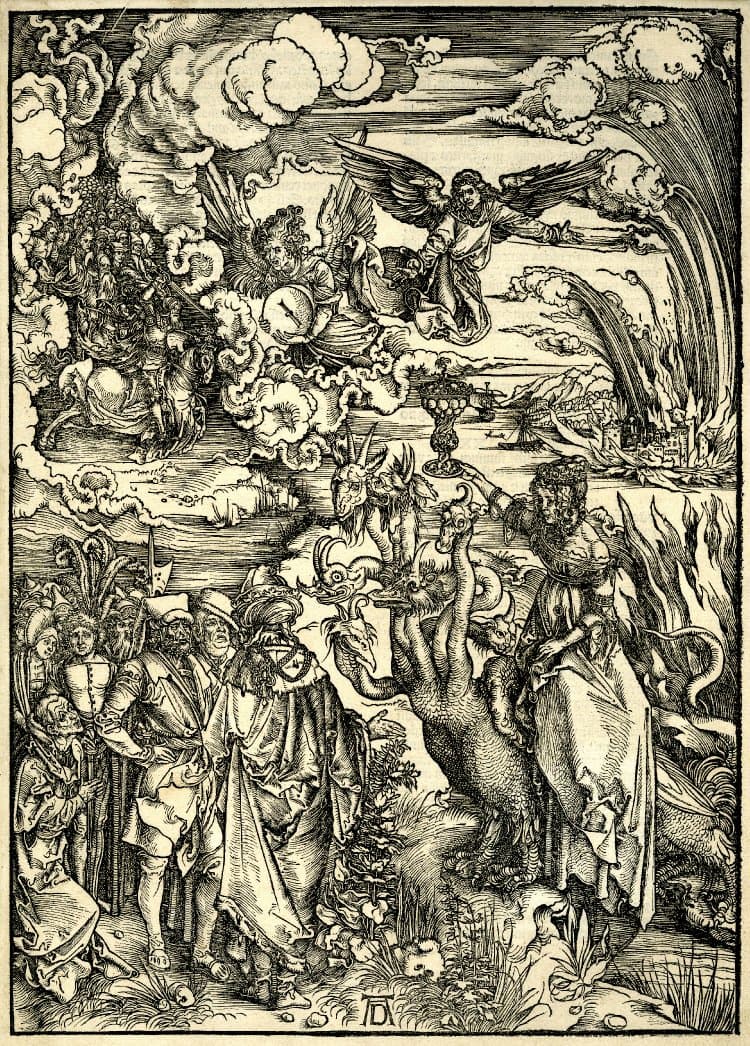

Next appears the Whore of Babylon (Revelation 17) who rides a beast with 7 heads and 10 horns. She is dressed in purple and scarlet, and wears gold, precious stones, and pearls, and carries a cup in her hand. It’s all symbolic: the seven heads of the beast represent 7 mountains, and 7 kings, and so on. She represents ‘the great city’, Babylon.

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 13. The Whore of Babylon, 1498

More beasts appear: a beast with lamb’s horns and one with seven heads that so fascinates the people that they follow it. (Revelation 13:1-18)

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 14. The beast with the lamb’s horns and the beast with seven heads, 1498

In Revelation 20:1-3 comes The angel with the key of the bottomless pit. The angel casts the dragon into the bottomless pit and shuts him up for a thousand years.

Dürer: Apocalipsis cum figuris: 15. The angel with the key of the bottomless pit, 1498

Now the music – John the Prophet’s complicated and symbolic vision was taken up by four very different composers.

Hilding Rosenberg: Symphony No. 4, “Johannes uppenbarelse”

Hilding Rosenberg (1892-1982) is regarded as Sweden’s first modernist composer. His fourth symphony, written in 1940 for baritone, choir, and orchestra, carries the subtitle of The Revelation of John (Johannes Uppenbarelse). In 1940, when he wrote the work, Denmark and Norway had been overrun by the Germans and France had fallen. Rosenberg wrote a dramatic work that has an elegant solemnity. The text consists of text from the Book of Revelation interspersed with poems by Hjalmar Gullberg.

Hilding Rosenberg: Symphony No. 4, “Johannes uppenbarelse” (The Revelation of St. John) – I. Detta ar en uppenbarelse fran Jesus Kristus (This is now the revelation of Jesus Christ) (Swedish Radio Chorus; Pro Musica Chamber Choir; Sixten Ehrling, cond.)

For the appearance of the Woman of the Apocalypse and the seven-headed dragon (Image 11), the setting gets quite excited.

Hilding Rosenberg: Symphony No. 4, “Johannes uppenbarelse” (The Revelation of St. John) – III. Recitative: Och ett stort tecken syntes (And there appeared great wonder in heaven) (Baritone, Chorus) —( Håkan Hagegård, baritone; Swedish Radio Chorus; Pro Musica Chamber Choir; Gothenberg Symphony Orchestra; Sixten Ehrling, cond.)

Rosenberg’s original setting was for reciter, choir, and orchestra, but in 1948-49, he revised it for Baritone instead of reciter.

Pierre Henry: L’apocalypse de Jean

One composer who also used a reciter was the French composer Pierre Henry (1927-2017). As a pioneer in the field of music concrète, he became known for his integration of noise into music.

Pierre Henry: L’apocalypse de Jean – Premier temps: Titre-revelation (Jean Negroni, reader; Pierre Henry, tape)

The entry of the four horsemen of the Apocalypse combines low piano pitches into the electronic mix.

Pierre Henry: L’apocalypse de Jean – P Deuxieme temps: Les quatre cavaliers (Jean Negroni, reader; Pierre Henry, tape)

Bengt Hambræus: Apocalipsis cum figuris secundum Dürer 1498 ex narrationem Apocalypsis Joannis

Bengt Hambræus (1928-2000) wrote his Apocalipsis cum figuris secundum Dürer 1498 ex narrationem Apocalypsis Joannis (Revelation with figures according to Dürer 1498 from the narration of the Apocalypse of John) in 1987 for bass, organ, and choir. The text is shared between the soloist and the choir: the soloist is John as he speaks and the choir takes on different functions, such as representing the invisible celestial powers. The organ music reflects the development of the drama. The start of the work is the nucleus of the piece.

Bengt Hambræus: Apocalipsis cum figuris secundum Dürer 1498 ex narrationem Apocalypsis Joannis (Versio Vulgata) (Hans-Ola Ericsson, organ; Olle Skold, bass; Swedish Radio Chorus; Stefan Parkman, cond.)

Peter Maxwell Davies: Resurrection

For his opera Resurrection, Peter Maxwell Davies (1934-2016) created an opera that takes a contemporary scenario and sets it into a morality tale. Rock music and advertising music fight with orchestral music. The Cat of the beginning eventually manifests as a dragon. 4 Surgeons, each with their own creed, operate on the patient to produce the Anti-Christ. We’re bombarded with ads for ‘Seven Stars Dentifrice’ to make your teeth ‘a-tingle with righteousness’.

Peter Maxwell Davies: Resurrection – Prologue: Dad (Lesley-Jane Rogers, Deborah Miles-Johnson, John Bowley, Mark Rowlinson, vocal quartet; Henry Herford, Dad; Mary Carewe, Cat; BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Peter Maxwell Davies, cond.)

And we’re invited to bet on some colourful horses: Victor, the White Horse; Mars, the Red Horse; Fame, the Black Horse, and finally Thanatos, The Daemonic, each with different odds. There are political rallies, and revivalist rallies, ending in the Song of the New Resurrection. It’s set to a cynical text, where lines such as ‘Solidarity with the workers!’ is followed immediately by ‘But keep them to their station…’. At the end, after dozens of advertisements for services, culminating in a real estate ad for ‘The new Jerusalem’, the Anti-Christ declares he’s ‘only an advert’.

Peter Maxwell Davies: Resurrection – Act: Song of the New Resurrection (Lesley-Jane Rogers, Deborah Miles-Johnson, John Bowley, Mark Rowlinson, vocal quartet; Della Jones, Antichrist; Neil Jenkins, Hot Gospeller; Mary Carewe, vocalist; BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Peter Maxwell Davies, cond.)

The connection with Dürer’s vision comes from the increasing visual references in the opera to the symbols and images from the Revelation of St John as Dürer pictured them. In his preface to the printed libretto, Maxwell Davies recommends the designer to study these woodcuts.

Each composer uses the world around him: Rosenberg reacts to WWII and creates a ‘flaming protest against racism and genocide…’. Pierre Henry’s creation for the reciter and tape is a monumental work. Hambræus took up a challenge issued by the German author Thomas Mann, who created an entirely fictional Apocalypse setting.

In his novel Doktor Faustus, written in 1947, Mann has his fictitious composer Adrian Leverkühn write an Apocalipsis cum figuris, supposedly performed in 1926, that reflected the styles and techniques of the 1920s. Hambræus saw this as an invitation to the composers of the world to create their own versions and wrote his Apocalipsis cum figuris secundum Dürer 1498 ex narrationem Apocalypsis Joannis (Versio Vulgata) in 1987. These are all very different compositions that look at the idea of apocalypse, the end of the world, and the chaos that surrounds everything. Using Dürer’s images as the base point for their work, composers are allying themselves with a vision created in anticipation of the end of the world.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter