Did you know that in the Latin language “Diva” is the word for goddess? We constantly hear it in connection with show business, where it is used to describe a highly temperamental and demanding person. In the world of opera, the meaning is probably most closely related to that of “prima donna,” a celebrated woman with a divine voice and an ego to match.

Joseph Lange: Mozart (detail), 1783

It’s not difficult at all to think of great operatic divas like Jenny Lind, Adelina Patti, Janet Baker, and the goddess of them all, Maria Callas. We are fortunate that technology has been able to preserve some of these incredible voices, but divas surely aren’t a recent invention. We can’t know exactly what divas around the time of Mozart sounded like, but composers during that time molded their music to the voices of the singers who were supposed to perform it. In a way, arias composed for a particular singer capture and preserve at least some characteristics of the voice. We thought it might be fun to look at three prominent divas from the time of Mozart and listen to music specifically written for them.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Der Schauspieldirektor (The Impresario), K. 486 “Silberklang: Jeder Künstler strebt nach Ehre” (Patricia Petibon, soprano; Markus Schäfer, tenor; Eva Mei, soprano; Oliver Widmer, bass; Concentus Musicus Wien; Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond.)

Catarina Cavalieri (1775-1801) “First Konstanze in Abduction”

Catarina Cavalieri

Born in Vienna, Catarina Cavalieri spent her entire career in the service of the Imperial Court Theater. Apparently, she ranked high among German singers but wasn’t all that much appreciated in her Italian roles. During the early stages of her career, Cavalieri was in need of “animation and accuracy, and a firmer assurance,” and she was also criticized for “almost unintelligible speech.” However, a contemporary dramatist writes, “she had a strong and pleasant voice, in both the high and low notes, a combination which one seldom encounters, and she sings equally well the most difficult passages.”

The Chimney Sweep

Portrait of Antonio Salieri by Joseph Willibrord Mähler

Cavalieri was a student of court composer Antonio Salieri, and she was almost certainly his mistress as well. Salieri also appreciated her impressive upper vocal range and her “extraordinary vocal stamina and flexibility.“ Taking advantage of her abilities, Salieri created the role of “Fräule Nannette” in the 1781 musical comedy The Chimney Sweep especially for her. Commissioned by Emperor Joseph II for his German company, the work was first performed at the Burgtheater in Vienna. As you can hear, Salieri composed brilliant showpiece arias for Cavalieri, including the much beloved “Wenn dem Adler das Gefieder” (When the eagle’s plumage).

Antonio Salieri: Der Rauchfangkehrer, “Wenn dem Adler das Gefieder” (Patrice Michaels, soprano; Classical Arts Orchestra; Stephen Alltop, cond.)

After the premiere performance, a critic wrote, “Demoiselle Cavalieri, who has the reputation among connoisseurs of being one of the first singers, and who through her beautiful singing also pleases the ordinary man, played the girl. Her acting is improving daily, and it is noticeable how much more trouble she takes if she is playing with others whose own acting contains more animation and accuracy. Her arms are still a little too stiff, bent too far forward and not loose enough: but she has already considerable expression in her bearing, has fine deportment, and soon will delight us as an actress as much as she does with her voice.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Abduction from the Seraglio, K. 384 “Ach ich liebte, war so glücklich” (Julie Fuchs, soprano; Balthasar Neumann Ensemble; Thomas Hengelbrock, cond.)

Abduction from the Seraglio

Mozart rehearsing with Catarina Cavalieri

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart would subsequently write Cavalieri some athletic and vigorous tunes in the Schauspieldirektor, but in 1782, he made her the first “Konstanze” in his Singspiel The Abduction from the Seraglio. Mozart was clearly trying to get the attention of Salieri and Cavalieri, as he tailored a number of bravura showcases for the diva’s voice. As he wrote to his father, “I have sacrificed Konstanze’s aria a little to the flexible throat of Mlle. Cavalieri.” But the real tour de force takes place in the second act of the so-called “Martern Aria,” one of the most difficult arias in opera literature. It demands strength for the long dramatic passages, great coloratura assurance, and a considerable vocal range. And it takes the voice all the way up to high D.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Abduction from the Seraglio, K. 384, “Martern von aller Arten” (Susanne Elmark, soprano; Sønderjylland Symphony Orchestra; Robert Reimer, cond.)

L’incontro inaspettato

Vincenzo Righini

Vincenzo Righini (1756-1812) hailed from Bologna, and he embarked on a promising career as a tenor in Parma, followed by performances in Prague, Brescia, Brunswick, Eszterháza, and Vienna. Actually, he first sang in Salieri’s La passione di Gesù Cristo. In addition, he established himself as the most sought-after voice teacher in Vienna, coaching Josepha Weber Hofer, the original “Queen of the Night,” and Princess Elisabeth von Württemberg, the bride of future Emperor Franz II. He even published a volume of solfeggio exercises that were reprinted throughout Europe. Righini received a commission from the Imperial Court Theatre for two operas featuring Catarina Cavalieri. L’incontro inaspettato features a plot related to Mozart’s Abduction, and Righini writes an exquisite aria for Cavalieri, supported by beautiful orchestration and an obbligato clarinet.

Vincenzo Righini: L’incontro inaspettato, “Per pieta, deh, ricercate” (Patrice Michaels, soprano; Classical Arts Orchestra; Stephen Alltop, cond.)

Adriana Ferrarese del Bene (1760-1804): “First Fiordiligi in Cosi”

Adriana Ferrarese

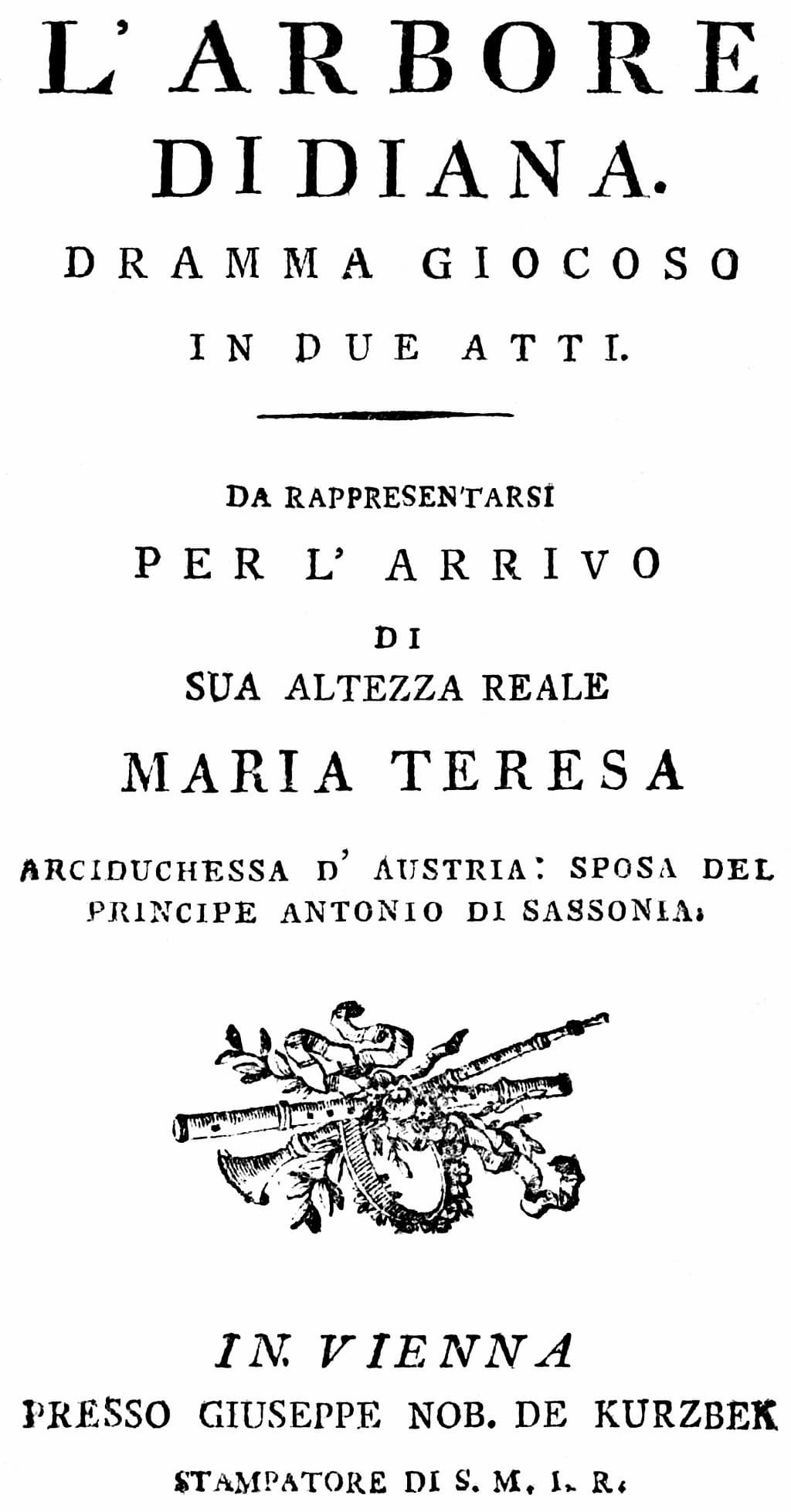

Adriana Ferrarese was first heard at the Ospedaletto in Venice in 1770, and after she eloped with Luigi del Bene in 1782, she sang in Livorno and subsequently in London. She made her Vienna début on 13 October 1788 as “Diana” in Martín y Soler’s L’arbore di Diana, in which she sang two substitute arias. An overexcited critic wrote, “she has in addition to an unbelievable high register and a striking low register, and connoisseurs of music claim that in living memory no such voice has sounded within Vienna’s walls. One pity only that the acting of his artist did not come up to her singing.” The Tree of Diana was composed by Martin y Soler to an original libretto of Lorenzo da Ponte, with whom Ferrarese was romantically involved. The plot revolves around goddess Diana and her attempts to defend her island as a stronghold of chastity. However, when she is confronted by the good-looking shepherd “Doristo,” her defences quickly fall down.

Vincente Martin y Soler: L’arbore di Diana, “Sento che dea son io” (Laura Aikin, soprano; Liceu Grand Theatre Orchestra; Harry Bicket, cond.)

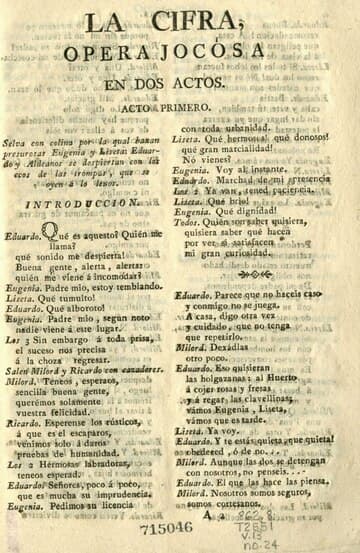

La Cifra

Salieri: La Cifra

Antonio Saleri presented La Cifra, a drama giocoso to an Italian libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte on 13 October 1790 in Vienna. It is the story of the Scottish lord Fideling who searches for a lost noblewoman with whom he has fallen in love. He is loved by Lisotta, the daughter of the town’s major, and by Eurilla, a simple peasant girl. As it happens in opera, Eurilla turns out to be the daughter of a nobleman, and she is reunited with Fideling in a happy finale. The role of Eurilla was tailored to Ferrarese’s talent, and features a vocal line showcasing the diva’s celebrated leaps between her head and chest voice. In the autograph score, Salieri penned the following note, “Pieces in the high serious style, but suitable for the person who sang them and for the situation in which she finds herself, and above all because they were composed for a famous prima donna, who could perform them most perfectly, and won the greatest applause.”

Antonio Saleri: La Cifra, “Alfin son sola… Sola e mesta” (Cecilia Bartoli, mezzo-soprano; Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment; Adam Fischer, cond.)

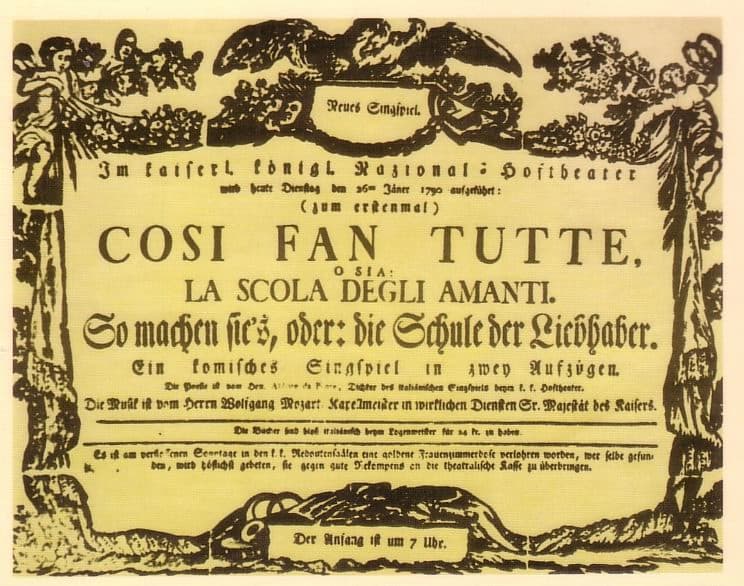

Cosi fan tutte

Mozart: Cosi fan tutte first performance

Mozart had the exceptional ability to compose music closely suited to his singers. Adriana Ferrarese’s singing career, from occasional prominence in serious opera to notoriety as a prima donna in Viennese opera buffa, certainly achieved crowning glory by her association with Mozart and Da Ponte in Così fan tutte. Some commentators suggest that Ferrarese was not a particularly great artist, and her comic and dramatic skills were at best uneven. “Her vocal equipment was impressive but incomplete and her performances less than inspiring.” Due to Mozart’s skill, however, he transformed this particular set of vocal skills and limitations into something of exceptional artistic value. Moreover, Mozart also had a great sense of humor. Ferrarese supposedly had the tendency to drop her chin and throw back her head while singing low and high notes respectively. As such, Mozart filled her showpiece aria “Come scoglio” with constant leaps. Maybe he took pleasure in watching her bob her head “like a chicken.” In the event, the role of Fiordiligi was clearly fashioned out of the temperament, vocal style, dramatic abilities and limitations of Ferrarese.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Così fan tutte, “Come scoglio”

Substitute for “Susanna”

Nancy Storace

Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro features a strong and very memorable female character named Susanna, the countess’ maid. In the original 1786 production, the role of “Susanna” was taken by Nancy Storace, a singer we will more closely profile in a follow-up article. The Vienna premiere enjoyed only moderate success, but three years later, a revival production was staged in Vienna. In this production, the role of “Susanna” was taken by Adriana Ferrarese. Mozart thought that Ferrarese was much better suited to the role of the Countess, but opera politics demanded that she star in the principal female role as Susanna. As he was clearly aware of the strengths and weaknesses of Ferrarese, he decided to write two new arias for her. First, he replaced “Venite, inginocchiatevi,” which requires a good deal of acting with “Un moto I gioja me sento,” K. 579. As he writes to his wife, “the little aria I have made for Ferrarese I believe will please, if she is capable of singing it in an artless manner, which I very much doubt. However, she seemed very satisfied.” However, Mozart gave her plenty of opportunity to shine in the rondo “Al desio di chi t’adora,” replacing “Deh vieni, non tardar.” As a member of the audience dryly noted, “Ferrarese’s rondo always pleases.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: “Al desio di chi t’adora,” K. 577

Luisa Laschi Mombelli (1763-1789) “First Countess in Figaro”

Luisa Laschi silhouette

Luisa Laschi made her Viennese début on 24 September 1784 in Cimarosa’s Giannina e Bernardone. A newspaper reports, “she has a beautiful clear voice, which in time will become rounder and fuller; she is very musical, sings with more expression than the usual opera singers and has a beautiful figure! Madam Fischer (Nancy Storace) has only more experience, and is otherwise in no way superior to Dem. Laschi.” She also appeared in Paisiello’s Il barbiere di Siviglia, a performance described as “much applauded.” After a brief stay in Italy, where she met her future husband, the tenor Domenico Mombelli, she returned to Vienna in 1786 to take the role of Countess Almaviva in Figaro.

Le nozze di Figaro

Mozart – Le nozze di Figaro – Marriage of Figaro and Susanna

While the character of “Susanna” represents the clever and feisty female servant of the commedia dell’arte, the “Countess” is the lonely, restrained, and courageous sufferer throughout most of the opera. At the beginning of Act II, Mozart wrote the most wonderful aria for Laschi. He provides her with an instrumental introduction to her aria, almost in the manner of a concerto. Clarinets, bassoons and horns supply sombre warmth, and set up the controlled vocal sorrow of what follows. As a scholar writes, by looking at the music we understand that “Luisa Laschi must have possessed a wonderful ability to spin a cantabile line, in the way Mozart so loved.” To be sure, Laschi possessed outstanding acting skills and commanded a solid vocal technique. As such, she would also feature in the first Vienna performance of Don Giovanni, a 1788 production that featured a newly composed duet for her and Francesco Benucci, Mozart’s first “Figaro”.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Le nozze di Figaro, “Porgi, amor, qualche ristoro”

L’arbore di Diana

Martin y Soler’s opera The Tree of Diana, title page of the libretto

In Martin y Soler’s opera The Tree of Diana, Luisa Laschi took on the role of “Amore.” That particular character appears alternately as a woman and a man, and placed considerable demands on her performance. A newspaper describes her as “Grace personified …; ah, who is not enchanted by it, what painter could better depict the arch smile, what sculptor the grace in all her gestures, what singer could match the singing, so melting and sighing, with the same naturalness and true, warm expression?” In addition, Laschi created the role of “Carolina in Salieri’s Il talismano and of “Aspasia” in Axur Re d’Ormus. Laschi was paired with Francesco Benucci in this complicated tale based on a libretto by Beaumarchais. From the tender duet between husband and wife at the end of the opera we certainly get a sense of Laschi’s vocal ability. She was replaced in the following season by Louise Villeneuve, who could also sing comic and serious roles equally well.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Antonio Saleri: Axur, Re d’Ormus, “Barbaro, il mio coraggio” (Eva Mei, soprano; Russian Philharmonic Orchestra; René Clemencic, cond.)