Benedikt Schack and Schikaneders Troupe

in performance, 1791

The composer and tenor Benedikt Schack (1758-1826) was a close friend of Mozart, and he was the first performer of the role of Tamino in The Magic Flute. Schack hailed from the Bohemian provinces of the Austrian Empire, but moved to Vienna in 1775 to study medicine, philosophy and singing. By 1786, Schack had joined the traveling theatrical troupe of Emanuel Schikaneder, working both as a tenor and as a composer of Singspiele. It was around this time that Mozart became a friend and professional colleague. Schack apparently asked Mozart for advice to help in composing, and a musical dictionary of 1811 relates the following anecdote. “Mozart often came to Schack to fetch him for a stroll; while Schack dressed he would sit at the writing desk and compose here and there a piece in Schack’s operas. Thus, several passages in Schack’s operas derive from Mozart’s own hand and genius.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Following Mozart’s death, Constanze, who had remarried Georg Nikolaus Nissen, was seeking information to include in her husband’s biography of Mozart. She wrote to Schack, “I could think of absolutely no one who knew him better or to whom he was more devoted than you… Of great and general interest will be what you can instance of Mozart’s few compositions in your operas.” Schack died before his was able to reply, but we do know that Mozart contributed a comic duet to Schack’s opera The Philosopher’s Stone.

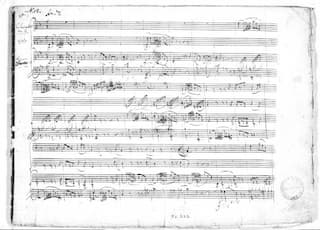

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: “Nun liebes Weibchen,” K. 592

Nikolaus Joseph Freiherr von Jacquin

Nikolaus Joseph Freiherr von Jacquin (1727-1817) was a famous botanist who was appointed director of the botanical gardens at the University of Vienna. For a time he was sent to the West Indies, the Caribbean, and Central America by the emperor to collect plants for the Schönbrunn Palace. For an extended period of time, Mozart lived very close to the Jacquin residence in the Landstraße, and Mozart and Nikolaus gave frequent house concerts. Nikolaus was an able flautist, and Mozart made fast friends with the Baron’s children. The youngest son Emil Gottfried had a good voice and Mozart wrote two songs for him published under the son’s name. “As Luise was burning the letters of her unfaithful Lover,” has since received the K. number 520, and “Das Traumbild,” eventually found its way into the Mozart catalogue as K. 530.

Kegelstatt Trio

Gottfried’s younger sister Franziska received piano lessons from Mozart, and in a letter he “praises her studiousness and diligence.” Mozart dedicated a considerable number of his works to the Jacquin family, most notably the “Kegelstatt Trio.” That work was first heard in the Jacquin residence in August 1786 with Mozart playing the viola, Anton Stadler the clarinet, and Franziska the piano.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Trio No. 2 in E-flat Major, K. 498 “Kegelstatt” (Stephen Kovacevich, piano; Jack Brymer, clarinet; Patrick Ireland, viola)

Baron Gottfried van Swieten

Baron Gottfried van Swieten (1733-1803) was Mozart’s most steadfast patron throughout the composer’s last decade in Vienna. The Baron had made his way up the diplomatic ladder with postings to Brussels, Paris, and Warsaw before becoming ambassador to Berlin from 1770 to 1777. He was an able composer and avid collector of music, who developed a taste for the works of Handel and Bach, as well as the Bach sons. The Baron played an important role in calling Mozart’s attention to some of the treasures of earlier music, and by early 1782, Mozart began attending and performing in the weekly concerts van Swieten held in his rooms at the national library. Mozart writes on 10 April 1782, “Every Sunday at noon I go to visit Baron von Swieten and there we play nothing but Handel and Bach. I am putting together a collection of Bach fugues, that is, Sebastian as well as Emanuel and Friedemann. I am also collecting Handel’s.” Just a couple of days later he wrote to his sister about the Prelude and Fugue, K. 394, he had just written. “I am sending you here a prelude and three-voiced fugue that will explain why I did not answer you at once, the reason being that I could not finish writing out all the little notes any sooner… I will compose five more fugues as soon as I have time and favorable opportunity and present them to Baron van Swieten, who has great treasure of good music, albeit in small quantity.” Through van Swieten, Mozart became more aware of Bach’s music and that of other Lutheran masters, and he remained a constant supporter of Mozart even during the lean years of the late 1780’s.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Prelude and Fugue in C Major, K. 394 (Glenn Gould, piano)

Aloysia Louisa Antonia Weber

Mozart was constantly in urgent need of money. During his stay in Mannheim, he supplemented his meager income by giving music lessons to the sons and daughters of the musical establishment. And so it came to pass that he was introduced to the four daughters of the Weber family. Aloysia Louisa Antonia Weber (1760-1839) not only became Wolfi’s student, she almost certainly became his lover as well. Aloysia was already a well-known soprano, and Wolfi told his father that she was certainly capable of being a leading diva. On 28 February 1778 he writes, “For practice I have set to music the aria Non sò d’onde viene. When it was finished, I said to Mlle Weber: learn the aria yourself. Sing it as you think it ought to go; then let me hear it and afterwards I will tell you candidly what pleases and what displeases me.

Mannheim Orchestra

After a couple of days, I went to the Webers and she sang it for me. I was obliged to confess that she has sung it exactly as I wished and as I should have taught it to her myself. This I know the best aria she has; and, it will ensure her success wherever she goes.” Wolfgang was eager to marry Aloysia, but Leopold would have none of it and sent his son straight to Paris. Aloysia writes, “My Dearest Wolfgang Amadé Romatz: … I hope this letter finds you well and warm. How unlike my sad heart! It is so cold since you went clattering off in that black carriage… Sometimes when I sing, it feels like all the distance between us disappears.” When Mozart returned from Paris several months later, however, Aloysia was no longer interested and he ended up marrying her sister Constanze.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, “Alcandro, lo confesso…Non so d’onde viene, K. 294

Sigmund Barisani

Sigmund Barisani (1761-1787) was head physician at Vienna General Hospital, and he was always ready to come to Mozart’s aid with medical advice. Twice, he performed emergency blood letting on Wolfgang. Wolfgang loved “Sigerl” dearly, and when his friend died on 3 September 1787, Mozart wrote in his diary. “This noble man, this best and dearest of friends and the savior of my life; all those who knew him will never recover… unless we are reunited in a better world.” Sigmund Barisani had early written the following poetic reflection in Mozart’s autograph album on 14 April 1787.

Though Britons, great in spirit as they are,

Know how to pay their tribute to thy art,

And rapt in admiration hear thee play

With mastery thy keyboard instrument;

Though Latins envy thy composer’s skill

And try to follow it as best they may;

Though long thy art has won thee fame and bliss;

By Bach and Joseph Haydn only matche’d;

Do not forget thy friend, whose happiness

And pride it is to know he served thee twice

To save thee for the world’s delight. This boast

Is yet surpassed by joy and pride to know

Thou art his friend, as he is ever thine.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Kyrie in D minor, K. 341 (London Symphony Chorus; John Constable, organ; London Symphony Orchestra; Colin Davis, cond.)

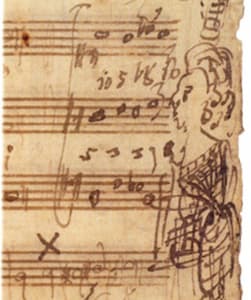

Portrait of Barbara Ployer on Mozart’s manuscript

Barbara von Ployer (1765-1811) lived in Vienna with her uncle, Court Councilor Gottfried Ignaz von Ployer, the trade representative of Salzburg in Vienna. Barbara was a fine pianist and she soon became one of his favorite students, however, she did not enjoy her counterpoint studies with Mozart at all. Mozart preserved a 1784 notebook containing exercises in four-part harmony, figured bass and studies in counterpoint. Apparently, Mozart also asked his student to come up with musical ideas of her own, with rather sketchy results.

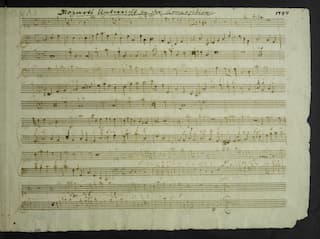

Mozart’s exercise book

Leopold Mozart curtly replied, “You want her to have ideas of her own — do you think everyone has your genius?” Nevertheless, Mozart was rather proud of Barbara as he writes to his father on 9 June 1784 “I am fetching Paisiello in my carriage, as I want him to hear both my pupil and my compositions.” The student in question was Barbara, and the work in question was almost certainly the Concerto in G, K. 453. With Mozart in attendance, Barbara played the work at her uncle’s house on 13 June of that year.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 17, K. 453 (Mitsuko Uchida, piano; English Chamber Orchestra; Jeffrey Tate, cond.)

Constanze Mozart

On a job-hunting tour, Mozart and his mother visited Mannheim in 1777. Mozart fell in love, but initially not with the 15-year old Constanze Weber, but with her sister Aloysia. After a brief and stormy love affair, Aloysia rejected Mozart and she went on to marry Joseph Lange. The Weber family moved to Vienna, and Mozart arrived in the city in 1781. Once his service to Archbishop Colloredo was terminated he was forced to leave the staff quarters and he found lodgings in the Weber household. Mrs. Weber soon became aware that Mozart was courting Constanze, now 19 years of age, and she requested that Mozart move out. The courtship continued, but they briefly broke up in April 1782. Apparently, Constanze had permitted another young man to measure her calves in a parlor game, and a furiously jealous Wolfie told her to get lost. However, reconciliation was quick and the marriage hastily planed in an atmosphere of crisis. Leopold was steadfast against the union, and since Constanze had moved in with Mozart, her family threatened to send the police if she did not return home. The only way to solve the predicament was to get married, and thus the couple stepped before the altar on 4 August 1782. History has treated Constanze harshly and unfairly, and she was severely criticized as unintelligent, unmusical and even unfaithful. In a word, unfit to be the wife of the great Mozart. Today we know that these charges against her are utterly unfounded.

Constanze was a trained musician and played a role in her husband’s career. Some of the extraordinary writing for soprano solo in the Mass in C minor was specifically written for Constanze, who premiered the work in Salzburg in 1783. In fact, as Maynard Solomon suggest, this work might have been a love offering.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Mass in C minor, K. 427 (Ileana Cotrubaș, soprano; Kiri Te Kanawa, soprano; Werner Krenn, tenor; Hans Sotin, bass; John Alldis Choir; New Philharmonia Orchestra; Raymond Leppard, cond.)

Joseph II

The Austrian Emperor Joseph II was crazy about Italian opera buffa! And since he had the required resources and lots of taxpayer money, he simply went ahead and founded a new opera company in 1783. Since the Emperor took his entertainment very seriously, he was looking to recruit some top talent. For one, he needed a house librettist, and his choice eventually fell on Lorenzo Da Ponte. Soon after he took up his post, Da Ponte met Mozart. Mozart was clearly a celebrity, but he had never written an opera buffa and Da Ponte eventually agreed to write him a libretto. As we all know, in the space of four short years they produced “The Marriage of Figaro,” “Don Giovanni,” and “Cosi Fan Tutte.”

Nancy Storace

However, the Emperor also needed exceptional singers, and for his prima donna he hired the English operatic soprano Anna Selina Storace, also known as Nancy Storace (1765-1817). Nancy hailed from London, but her career really took off in Italy. She was only 17 when she arrived in Vienna, and she immediately commanded attention. Mozart had first seen Nancy when she made her Viennese debut in Salieri’s La Scuola De’Gelosi. Like the rest of Vienna, he immediately fell in love with her. Mozart specifically wrote the role of Susanna in his Le nozze di Figaro for Storace. He made last-minute changes to respond to Storace’s vocal need, and the character of Susanna was certainly based on the lively active style of Nancy.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Le nozze di Figaro, K. 492 (Giuseppe Taddei, baritone; Anna Moffo, soprano; Eberhard Wächter, baritone; Elisebeth Schwarzkopf, soprano; Fiorenza Cossotto, mezzo-soprano; Dora Gatta, soprano; Ivo Vinco, bass; Renato Ercolani, tenor; Piero Cappuccilli, baritone; Elisabetta Fusco, soprano; Philharmonia Chorus; Philharmonia Orchestra; Carlo Maria Giulini, cond.)

Franz Anton Mesmer

During his initial years in Vienna, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart made the acquaintance of Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815). Mesmer was a trained physician who hypothesized that it was essential to maintain equilibrium between the natural magnetic fluid that filled all living things, and the magnetic fluid that he thought filled the universe. He treated patients in his elegant private residence by fitting magnets to various parts of the body. The wonderful and dramatic cures he achieved via this method were initially termed “animal magnetism,” and inspired lavish parties and musical soirées. Magnetism became a cult and Mesmer became its high priest.

Maria Theresia von Paradis

However, Mesmer’s reputation was utterly destroyed by his failed treatment of Maria Theresia von Paradis. Paradis was the daughter of the Imperial Secretary of Commerce and Court Councilor to Empress Maria Theresa, and she had lost her eyesight at age 4. Initial magnetic treatment did restore her eyesight, but failing to correctly identify the underlying cause, the unfortunate young woman relapsed into her previous blind state. The press was all over the story in a real hurry, and once the University of Vienna renounced Mesmer, he quickly left the country and settled in Paris. Maria Theresia von Paradis (1759-1824) was an accomplished singer, talented composer and virtuoso pianist who performed in various Viennese and European salons and concerts, and Mozart composed the concerto K. 456 probably on commission from her.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 18 in B-flat Major, K. 456 (Mitsuko Uchida, piano; English Chamber Orchestra; Jeffrey Tate, cond.)

Mozart: Requiem

The Count Franz von Walsegg (1763-1827) was an aristocrat living in Stuppach Castle near the town of Gloggnitz. He was a passionate lover of music and the theatre, and every week on Tuesday and Thursday he hosted quartet performances. A biographer wrote, “So that he would not lack for new quartets, in view of so frequent productions of them, Herr Count not only procured all those publicly announced but was in touch with many composers, yet without ever revealing their identities… they delivered to him works of which he retained the sole ownership, and for which he paid well.” But what is more, Count Walsegg liked to pass off his commissioned compositions as his own in private performances. Sadly, in 1791, his twenty-year old wife Anna passed away and the grieving Count, only 28 himself at the time, would never remarry. The Count was a fellow Freemason, and he commissioned Mozart to compose a Requiem mass for Anna. Mozart died before the completion of the Requiem, and Constanze arranged for several other composers, most notably Franz Xaver Süssmayr, to complete the work in order to gain the remainder of the sum Walsegg had promised. A completed version dated 1792 was delivered to Count Franz von Walsegg. If the Count had hoped of passing the Requiem off as his own compositions, he would have been frustrated by a public benefit performance of the work for Constanze. Constanze was responsible for a number of stories surrounding the composition, including the claims that Mozart received the commission from a mysterious messenger who did not reveal the commissioner’s identity, and that Mozart came to believe that he was writing the requiem for his own funeral. When Beethoven was asked to comment on the masterpiece, he is quoted as saying that “whoever wrote the Requiem was a genius.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Requiem in D minor, K. 626 (completed D. Druce) (Nancy Argenta, soprano; Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano; John Mark Ainsley, tenor; Alastair Miles, bass; Schutz Choir of London; London Classical Players; Roger Norrington, cond.)

Marvellous commentary of Mozart’s circle of friends. How he found time to compose six hundred odd works, socialise , and travel ,in such a short life span is a mystery to me.